A Custom Harley-Davidson Built for Big Twin Magazine

This article was originally published in the June-July 1999 issue of Cycle World’s Big Twin magazine.

They seem to be everywhere, those world-class, exotic customs that stun your brain every time you see one. They’re on the road and you see them on television, and you drive your wife nuts pasting magazine pictures of them on your refrigerator door. You crane your neck for a decent view of them when they flash by, and when you see one parked, you pause by it for long, quiet minutes with your hands in your pockets, wondering who made such a gorgeous machine.

That seductive, chrome-and-candy creature might have come from any one of a dozen people who can transform raw steel into roaring, rolling flights of fancy. But the odds are virtually non-existent that any of them came from that big, red brick building in Milwaukee.

Sturgis, Daytona, Laughlin and a hundred other custom shows around the globe boast thousands of interpretations of the Harley-Davidson motorcycle. But are they really Harley-Davidsons? Do they have genuine Harley-Davidson motors in genuine Harley-Davidson frames? What about the bolt-on parts; are they genuine Harley-Davidson?

“Since we all agreed that we wanted a motorcycle that was truly representative of Motor Company standards, Fuller decided to do no cutting or modification to the stock frame, and to use wherever possible parts that are all available to the average Harley owner.”

Brian Blades

Chances are, they’re not.

These days, there are untold thousands of aftermarket accessories with which to build an exotic Harley custom; and that’s a very good thing, because it makes personalizing a bike easy and simple. But there is, in fact, so much aftermarket stuff available that one wonders if trying to build an exotic custom starting with a genuine Harley-Davidson is actually a liability.

More than a year ago, we posed that question to some Motor Company executives. “Why are all the customizers around the world setting the styling agenda,” we asked, “and not you?”

The Harley guys shrugged and explained that, based on exhaustive research, their motorcycles are specifically created to appeal to the largest number of potential buyers possible. They also allowed as how they have to be able to mass-produce those bikes on the assembly lines at York and Kansas City. “We build bikes for the riding enthusiast,” they said, “the people who want a motorcycle that is dependable, yet still has that traditional Harley-Davidson look. And everyone’s tastes are different: One man’s custom is another man’s nightmare.”

We told them we understood that trying to please everyone all the time is an impossible task for any company; yet, Harley designs are so successful, so wildly popular, that manufacturers the world ’round are shamelessly copying them.

“Given that,” we asked, “doesn’t it drive you crazy that any time a stock Harley is parked next to a Harley-esque custom that uses not one authentic H-D part, the custom gets all the attention? Look at what people are creating from your machines; wouldn’t you like to build something over-the-top like that? Something that would make a statement and set the bike world on its ear like the Corvette, the Viper and the Prowler did when they were introduced as concept cars? Why don’t you build a radical genuine Harley custom?”

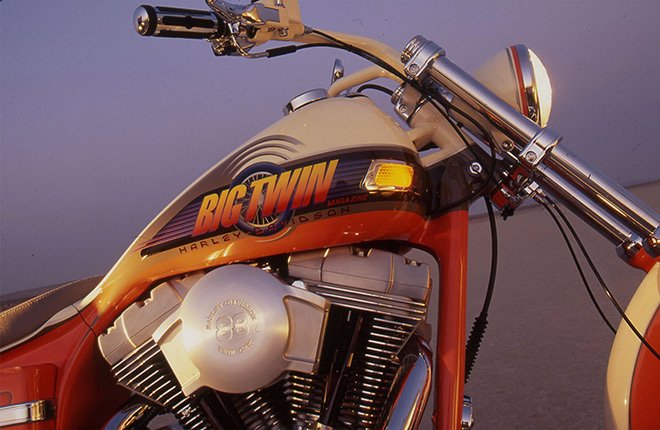

Despite its high style and one-of-a-kind appearance, the Big Twin Custom III uses mostly Harley-Davidson equipment. Many of the pieces, such as the exhaust system, are Screamin’ Eagle bits from Harley’s P&A Division, while others are original-equipment components (the gas caps and gauges are good examples) mildly tweaked by the bike’s creator, Wyatt Fuller.

Brian Blades

“Radical?” they asked.

“Yeah, way radical,” we said, “and build it for Big Twin Magazine. For the last couple of years, we’ve had a leading customizer build us our annual project bike. The most recent one was completely aftermarket; it used no genuine Harley parts at all. So, why don’t you build our next one? It could be conceived by a Harley designer and built exclusively with Harley hardware.”

We didn’t think this conversation had really had any impact until a few months later when we got a call from Milwaukee. To our amazement, management had decided that building a custom for Big Twin was a hell of a good idea. They wanted to have their Exclusive Design Consultant, Wyatt Fuller, create the bike around a Dyna Wide Glide, and they stipulated that it would be made either with off-the-shelf Harley-Davidson components or custom parts fabricated by Fuller or some of H-D’s engineers.

Obviously, we agreed. We were both elated and flattered, because the building of any kind of radical custom was an unprecedented act for The Motor Company. Indeed, for H-D to create such a bike at all was revolutionary; that they would make it for us was inconceivable.

We’ve known of Fuller and his sheetmetal artistry for some time, so we were eager to meet with him to discuss the concept. Our first design conference with him was very casual, taking place during the 95th Homecoming Reunion in June of 1998. We talked while we sat in the grass at Milwaukee’s Lakefront Park, surrounded by exhausted riders who had just ridden through four days of rain and wind.

When Fuller asked what we had in mind, we said we might like to see something that combined traditional customizing with a high-performance look—sort of like Fifties’ bob job meets dirt-tracker. It would be a lean and elegant stoplight gunslinger with the motor to back it up. “After all,” we said, “the word is that Harley has a new motor coming out, so how about making this bike the first custom using that engine?”

Fuller also thought that was a fabulous idea, and we shook hands on it. Throughout this entire project, that handshake was the most formal contract we signed.

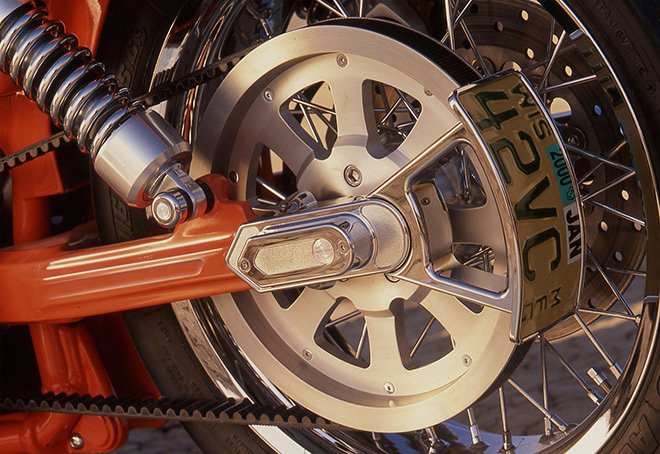

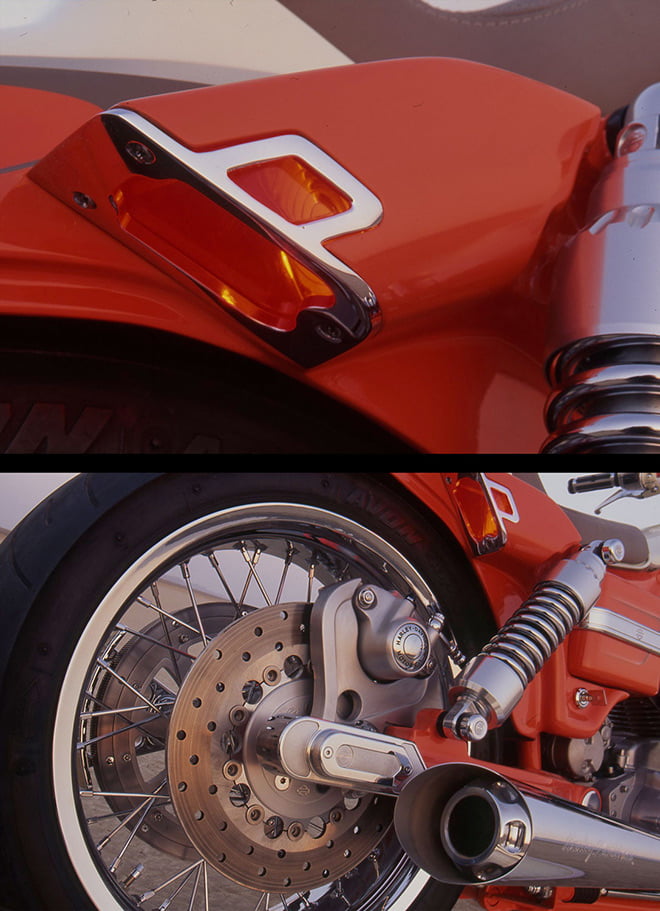

Gates Rubber says the one-inch drive belt it made especially for this bike is as strong as the standard 11/2-inch belt. The rear-axle covers are current H-D P&A pieces, while the license-plate holder is a prototype for a possible future P&A item. The nifty, integrated rear turnsignals are one-off Fuller designs that even incorporate side marker lights.

Brian Blades

After the dust finally cleared from the 95th Anniversary madness, the factory supplied Fuller with a new Twin Cam 88 Dyna Wide Glide, and Fuller went to work. Since we all agreed that we wanted a motorcycle that was truly representative of Motor Company standards, Fuller decided to do no cutting or modification of the stock frame, and to use wherever possible parts that are available to the average Harley owner. He would, however, create some unique bodywork to fit the theme of the bike—and when it comes to bodywork, Wyatt Fuller has few peers.

Fuller’s technique is different than that of other designers we know in that he doesn’t sketch his designs beforehand; he develops a basic vision in his mind, usually starting with the seat and rear fender area, then sets to achieving that vision, one piece at a time.

In this case, Fuller had recently completed a fantastic custom FXR for H-D Vice President Clyde Fessler (“Minimalism,” Big Twin’s December-January, 1999 issue) and wanted to make the lines of the seat area on our custom flow as on that bike. To achieve this effect, he relied on some visual trickery in the form of judiciously applied thin-wall tubing. The graceful lines flowing from the tank, around the seat and down to the rectangular boxes on the sidepanels were created with tubing. After the tubing was molded in place, the interior area was then filled in with sheetmetal. As a result, what looks like frame members surrounding the boxes are actually cosmetic fabrications rather than structural members, and the end effect is a strong yet graceful continuity.

As for those boxes themselves, the right one covers the battery and the left one conceals a lot of the electrics. Fuller got advice from friends that he somehow ought to hide the boxes; he disagreed, figuring that this is a Harley, after all, and the boxes are an integral part of the Dyna look. Better to make them look good than hide them. “I knew that the Parts & Accessories Division was coming out with those box covers and the chrome straps on them,” said Fuller, “and I figured the easiest way to make people recognize this bike as a Dyna was to incorporate them into the design.”

Wyatt Fuller was helped immeasurably by Len Courtney, who applied the Glass Kote finish on the motor; Randy Davis, who fabricated the seat; Markland Industries, who turned the chrome work around in 24 hours; Dawne Holmes, for being … well, Dawne Holmes; Rich Machesney, Fuller’s right-hand man who does all the CNC millwork; and Jim (Buffalo) Horn and Bart (Painter) Carter of C&H Customs, who applied the base coat of paint.

Brian Blades

Because most bikes look only as low as the lowest part of their seats, the seat becomes a critical design element. Again, Fuller created the illusion of having lowered the bike by running tubing down from the tank to the seat, and then angling the seat so that its front is actually higher than stock, though the bottom is lower.

After the seat area was resolved, Fuller then started from the rear of the bike and worked his way forward. “We put a piece of one-inch-square tubing on each leg of the swingarm,” he explained, “to accent it and draw the eye back to our axle covers, which are off-the-shelf items. With the gas tank, we just cleaned up the front of it and did another little visual trick that makes the frame look like it’s a little bit stretched, even though it’s not. We hid the tank mount but left the front mounting hole, then ran the wiring through that hole.”

The net visual effect is that the front of the bike is clean and uncluttered, and the tank looks stretched and closer to the frame. It’s hard to believe that such a pleasing effect could be coaxed from a non-Softail frame that has been neither stretched nor lowered.

Although the steering neck wasn’t raked, the triple-trees were kicked out about 41/2 degrees, which also gives the bike the illusion of having being stretched. The handlebars are Fuller’s favorites, FXLR bars that, as he puts it, “have been lowered two inches to have kind of a flat-track look.”

Some of the most intriguing elements of Fuller’s design are the turn signals. Up front, the signal lights have been integrated into the gas tank, and out back, they’re integrated into the ends of the fender rails. Not only do the front blinkers look cool, they’re also legal, because the sight angle and lens size fit within current Department Of Transportation standards—and Fuller was bound and determined to adhere to DOT safety specs. “We made it all work, “he says proudly, “and as silly as it sounds, it worked with the Narrow Glide trees because they pulled in the uprights so you can see each turn signal from the opposite side. If we had used the Wide Glide front end, it would not have worked and we’d have needed to do something else.”

Kicking out the triple-trees 41/2 degrees gave the front end a raked look, even though the steering angle remains stock at 32 degrees. The headlight was lifted from a Springer, and the handlebars are modified FXLR units.

Brian Blades

As for the bodywork on the rear fender and gas tank, well, that’s pure artistry, the type that is embedded in the genes. You can either do things like this or you can’t. The only way to describe that level of brilliance is simply to say that Fuller started pounding out metal until he liked what he saw, then he put it on the bike. The results, as you can see, are spectacular and, in our opinion, advance the art of motorcycle customizing.

Once the shape of the bike was established, the next task was to select parts that accentuated the basic form. The headlight is from a Harley-Davidson Springer. Underneath the lower triple-tree, Fuller fabricated a T-junction for the brake hydraulics and employed thin, black Kevlar lines from Russell. “Those hoses are kind of nice,” he says, “because visually they go away.” The front brakes are floating rotors from the factory, but Fuller fabricated the rotor center pieces. The fork is stock, right down to the springs. The handlebar controls also are off-the-shelf Harley pieces, as are the mirrors. The unique foot controls were fabricated by Fuller especially for this machine. The dash panel started out as a Dyna Low Rider unit that Fuller tapered then “sucked in,” and he replaced the gas gauge with a stock, 3-inch tachometer. The unique, chromed gas caps (the left one is fake) are stock items he modified.

On the outside of the Twin Cam motor, everything is Harley-issue equipment with the exception of the stunning air cleaner, a design Fuller has wanted to use for quite a while. As far as we’re concerned, The Motor Company should start offering these beauties for sale right now, because Milwaukee would not be able to crank them out fast enough to meet demand.

Inside the engine pumps a Screamin’ Eagle 94-inch big-bore kit installed by legendary Harley tuner Don Tilley, who did some mild head porting while he was in there. Tilley also bolted up a 42mm Screamin’ Eagle Flatslide carburetor by Mikuni and a Screamin’ Eagle 2-into-1 exhaust.

The billet air-cleaner cover is Fuller’s favorite piece on the entire motorcycle. It would be expensive to duplicate for aftermarket production, but he feels The Motor Company could sell all they could build anyway. So do we.

Brian Blades

The wheels—21-inch front and 18-inch rear—were pieced together by Fuller to accept that fat. 170/60 Avon AM 23 rear tire; the front rubber is an original-equipment MH90 Dunlop. The belt pulley is stock, but was split and narrowed to accommodate a trick, one-inch belt specially rewoven by its maker, Gates Rubber, to be as strong as the inch-and-a-half stock belt.

That’s the sum of the hardware inventory, and per the agreement, every part is either available to the general public or was made by Fuller, a Harley-exclusive contractor. The triple-trees, footpegs, coil cover, air cleaner, license-plate bracket and narrowed pulley all are prototype Fuller designs that currently are being considered for production by Harley’s P&A Division.

After Fuller had a rolling mockup of the bike, the next consideration was texture and paint. Would chrome and flamed candy colors be the direction, or something more subtle? On the motor, Fuller knew he wanted to use the brushed-aluminum technique he first employed in 1996. “At first, I didn’t know if people would care for that look,” he said, “but they really did. If a brush-finished part is hanging on a dealership wall, it’s hard for people to visualize what it’ll look like on a bike. But when they see it all put together, they really like it.”

Once he decided on the brushed-aluminum effect, Fuller then chose an understated paint scheme that would blend with and accentuate the metal. Candy lacquers are indeed beautiful and long associated with custom machines, but unless they’re matched with copious chrome, they can also appear hard and brittle. For the perfect matchup of paint to metal texture, Fuller chose a light color called Vanilla Shake (which is exactly what it looks like) from PPG Paint’s Soft and Subtle chart. The contrasting color is called Medium Orange and is off PPG’s Hot Licks chart. The desired end effect was a cohesiveness of theme, and with these two attenuated colors, Fuller got it right.

Simple. Elegant. Ridable. Practical. It’s everything that a good custom should be but that most are not. Plus, it would be fairly easy to replicate for limited-volume production.

Brian Blades

The graphics were airbrushed by Dawne Holmes, which is like saying Michael Jordan made a basket or Mark McGwire hit a baseball real hard. Apparently, Holmes (“Dawne Holmes, Artist in Motion,” February-March, ’98 Big Twin) is simply an angel of creativity visiting Earth, for she airbrushes images that are as close to heavenly as graphics get. Not only does the big image on the tank have a striking presence, but Holmes’ attention to detail—the color blending and striping on the handlebars, swingarm and fork—is what gives the bike a finished look. It’s a look that David Edwards, Editor of our sister publication, Cycle World, and no stranger to custom motorcycles, says “takes the bike that last 10 percent to perfection.”

Well, there is one aspect of the bike that is better than looking at it: riding it. The mildly raked trees, Don Tilley’s Force-Five motor and that whopper of a rear tire all conspire to create a ride that is so much fun, it ought to be (and, in a mere eyeblink, can be) illegal. The Dyna custom accelerates like something launched out of a catapult, is reassuringly stable, and retains all the cornering clearance of the stocker.

So if, based on the looks of this bike, you thought it somehow lacked balls, let us assure you that riding it, standing near it or even watching it as it thunders past will instantly change your mind. Stated bluntly, this motorcycle is a badass that most definitely walks the walk. No matter where it goes, it’s the alpha male, and whether it’s in motion or merely parked among other bikes, it commands an air of authority and dominance.

The Harley-Davidson Motor Company is very proud of the Big Twin Custom III, and to put it mildly, so are we. In our minds, it’s nothing less than a revolutionary new direction in the motorcycle form.

Part of our handshake agreement with Harley is for us to keep the bike for a year and use it—a lot. Our mission is to put as many miles on it as we can, and ride it to as many weekend events as possible. In the spirit of that contract, we’ll do our very best to hold up our end of the bargain.

Hey, it’s a thankless job; but somebody has to do it.