Riding Impression Of The 1998 Harley-Davidson FXD Dyna Super Glide

This article was originally published in the February-March 1998 issue of Cycle World’s Big Twin magazine.

The 1998 Dyna Super Glide is Harley’s low-price leader in Harley’s Big Twin line.

Brian Blades

Twenty-six-hundred bucks. That’s how much money separates the ’98 Dyna Super Glide from the next least expensive Big Twin. To get a Dyna Convertible or Low Rider, or any Softail, you’re going to have to lay out at least 25 percent more than you would for this FXD, Harley’s low-price leader in the Big Twin line.

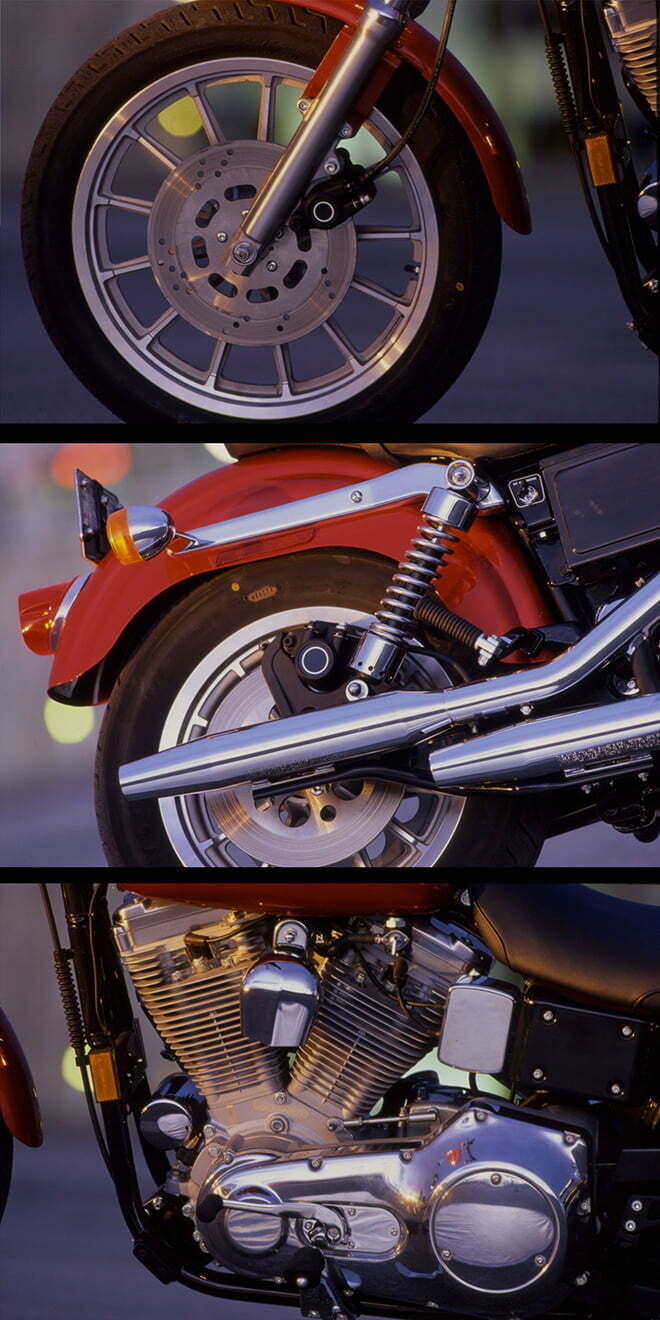

For that you get a lot of motorcycle and not a lot of frills. Tachometer? Nope. Just the singular speedometer perched on the top triple-tree, right above the galvanized steering-head bolt that looks like it came off a tractor. Extra chrome? Nada. Just the basics and nothing else; even the headlight shell is painted. Blacked-out cylinders with polished fin ends? You’ve got to be kidding. What do you expect for $10,865 ($11,015 in pearlescent paint)? Certainly not highway pegs or dual Bob fuel tanks, or a tufted seat. No, what you get is essential Big Twin, and nothing else.

Fortunately, Big Twin essence is pretty neat stuff. The FXD uses the same basic engine and transmission as all other Big Twins, but at less than 600 pounds dry, it’s the lightest of the bunch. And while all the Softails have been given Bonneville gearing (2.93:1 in top) to reduce their shaking at highway speed, the Dyna models, with their rubber engine mounts, can tolerate shorter gearing—fully 7 percent steeper at 3.15:1. That has exactly the same effect as a 7-percent torque increase.

Despite its single disc brake front and rear, the Dyna Super Glide stops quickly and easily, thanks in some part to its light weight.

Brian Blades

Consequently, the Super Glide is quick, even with stock mufflers and air cleaner. It scoots hard away from a stoplight with almost no clutch slippage at all in first, and it just clicks on up through the gears at a rapid rate. In seemingly no time, you can get up to the 75-to-80 mph fast-lane cruising speed that seems to be standard on many freeways these days, and run there all day. The only drawback is a slight buzzing in the seat that we haven’t noticed on previous Dynas; handgrips and footpegs are dead smooth at these speeds.

Equally impressive is the smoothness of shifting. Harley hasn’t been talking about any changes in engine design, but all recent models we’ve ridden—including this FXD—have shifted noticably better than bikes built a few years ago. Attribute some of that to refinements in the clutch that have reduced clutch drag; The Motor Company shifted clutch-plate suppliers in 1994. If a clutch disengages fully and cleanly, neutral is easier to find and shifting effort is reduced. In addition, Harley has overhauled its entire gear manufacturing operation with the installation of expensive, German gear-grinding machines; and perhaps tolerances throughout the transmission have also improved. Or perhaps the high-contact-ratio gears that were substituted a few years ago to reduce noise make the difference. Whatever the cause, we can all appreciate shifting that’s more “click” than “clunk.”

When the Dynas were designed, they were given a one-piece steering-head investment casting that was jigged to the rest of the frame independently of the actual steering bearing locations. What this means is that Harley can easily manufacture Dynas with different head angles.

If you prefer the raked-out look, the Super Glide is not the bike for you; like the Convertible, it runs a 28-degree head angle. That doesn’t result in the long, custom look of a Low Rider, which has a 32-degree head angle that pushes its front wheel fully 3 inches farther forward than the Super Glide’s, but that conservative angle does result in the best steering of any Big Twin. With just 4.1 inches of trail, the FXD front end doesn’t flop side-to-side at parking-lot-speed turns the way some more raked-out Harley models will, and it doesn’t require daily workouts at Gold’s Gym to turn at speed. It just goes where you point it readily and easily, quickly building confidence with the steering stability.

The Super Glide sits an inch-and-a-quarter lower on its thinner seat and offers slightly less ground clearance before the footpegs and sidestand begin to touch down around corners.

Brian Blades

With about three-quarters of an inch less suspension travel than a Convertible, the Super Glide sits an inch-and-a-quarter lower on its thinner seat, and it offers slightly less ground clearance before the footpegs and sidestand begin to touch down around corners. But that won’t happen until you’ve about doubled the number posted on one of those yellow curve-warning signs. This is one good-handling Big Twin.

You’d think that the solo front disc might not be up to the task, since the rest of Harley’s lineup is rapidly going the dual-disc route. But the FXD is light, and the company has been increasing the leverage for all its front brakes by reducing the master cylinder piston size; so, the Super Glide’s singular front brake stops it just fine. The dual discs of other models are not noticeably more powerful.

Perhaps the only component not included on the Super Glide that’s really missed are highway pegs—though the brackets remain on the frame for their mounting. With its low seat and the traditional, alongside-the-engine footpeg location, the FXD is not a roomy ride. So, if you’re intending to do any touring on a Super Glide, you should plan on filling those empty brackets first.

Which brings up the ideal role for the FXD: blank pallette on which to draw your own ideal Big Twin, without leaving a bunch of expensive, “Live to Ride, Ride to Live” medallions piled up in the corner of your garage when you’re done. This simplest of Big Twins has almost nothing on it that it doesn’t need; so, when you begin modifying it, you’ll simply end up trashing fewer stock parts. With its good handling, light weight and rubber-mounted engine, it’s the ideal basis for a performance-oriented custom; and the money you saved on its purchase will buy a lot of hot-rod parts.

Smoothness of shifting can be attributed to the clutch redesign.

Brian Blades

Want to improve the braking to current, state-of-the-art levels? Well, take solace in the fact that you’ll only have to dispose of one stock front-brake caliper at the swap meet, not two. Want more ground clearance? You can jack the FXD up to Convertible levels, and end up with higher-quality aftermarket suspension components than the stockers. Want to go touring? There’s a wide range of saddles, bags and windscreens available that will bolt right on. About the only thing that will be difficult to do is build a long, low custom from this Super Glide; the stock frame doesn’t lend itself to the stretched-out look, and most professional custom builders will tell you that it’s not worth the considerable bother to rake out a stock Dyna chassis. If that’s the look you’re after, start with another bike, or else plan on buying an aftermarket frame.

No, the FXD Super Glide is the most function-intensive of the Big Twins. It offers better steering, less weight and more stock performance than anything else in the line.

If enhancing those traits even farther appeals to you, and if you’re much more interested in clean, simple looks than in the ultimate custom design statement, you couldn’t find a better—or less expensive—place to start.