The Stranger-Than-Fiction Saga Of Harley-Davidson’s Japanese Stepchild

The V-Twin engine is probably the most recognizable piece at first glance, but if you take a second look, there are a lot of things that shouldn’t or could’t be.

Brian Blades

This article was originally published in the June-July 1998 issue of Cycle World’s Big Twin magazine.

One of the secrets of success in any novel, stage or screenplay is the power of what the textbooks call the Willing Suspension of Disbelief. What this means is that those of us in the balcony, the bleachers or curled up on the couch have to accept facts, logic and circumstance beyond what our experience would predict.

Prepare to do that now.

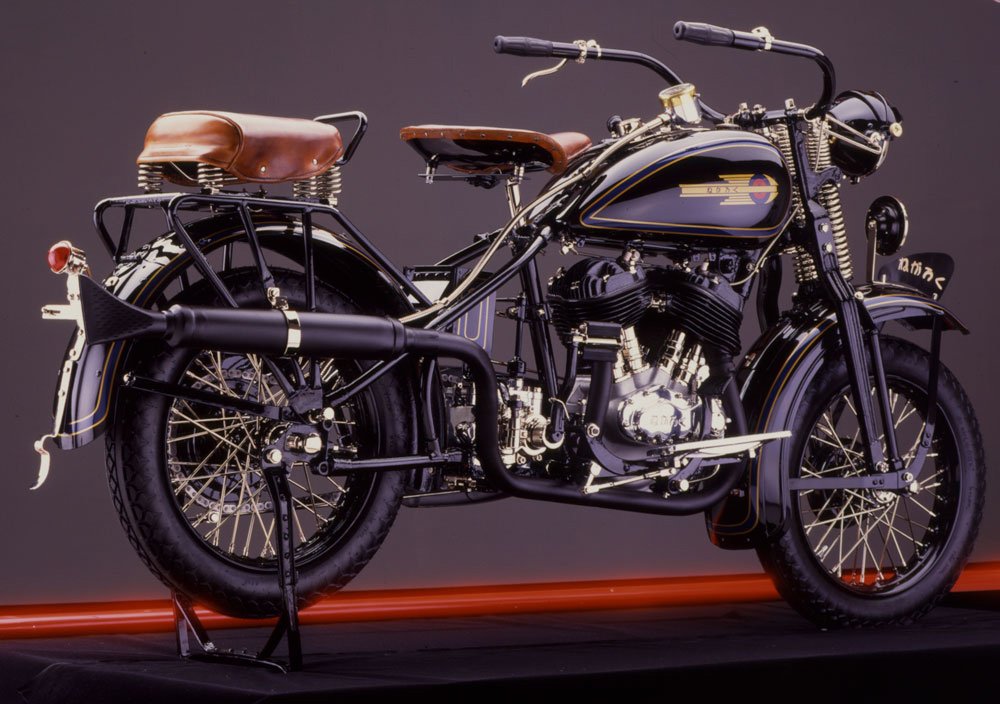

At first glance, much of what you see here seems instantly recognizable—a V-Twin motor, for example. But a second glance reveals a lot of things that shouldn’t or couldn’t be. That’s because this motorcycle is the rarest of the rare. As far as our inquiry can tell, there only two of these motorcycles left in existence. And this wasn’t a prototype. This motorcycle, the venerable Kurogano, or “Black Iron,” was mass-produced by the Japanese during WWII and saw duty in the home market and overseas.

Suspend your disbelief a bit more when we tell you that this particular bike appeared magically in the Sierras of Central California, where it was wounded by a bullet from an irresponsible deer hunter. How did it get from Japan to California? No one knows.

The restoration of this black beauty has been in progress, in fits and starts, for about 30 years. And it wasn’t until after the restoration was at the not-quite-complete stage seen here that the owner could really document what he has. Not only that, what he has isn’t what he thought it was.

As we progress through this story, keep looking at that V-Twin and keep in mind a bit of sweet irony: The Japanese motorcycle industry was started, nurtured and expanded with the expertise, engineering and encouragement of Harley-Davidson.

The Documented History

Shortly after the idea of the motorcycle synergized with American enterprise and Yankee know-how, Harley-Davidson and rival Indian exported worldwide.

In the 1920s, Japan hadn’t become a truly industrialized nation, and Harley-Davidson owned the lion’s share of the world market. H-D was the official mount of Japan’s police, army and even the Imperial Guard. The demand for Harleys in Japan was so strong that Milwaukee established a complete system of dealers, agencies and spare parts, all of it under the banner of the Harley-Davidson Sales Company of Japan.

As an odd sort of omen—and aside from the bike on these pages—in 1924, the Murata Iron Works began making a copy of the 1922 H-D pocket-valve J model. It was tested by the Japanese army and rejected as poorly constructed. The lesson was taken to heart, clearly, as Murata went on to build the Meguro, itself the ancestor of Kawasaki.

But then, in 1929, the world’s economy got the staggers and the yen’s value dropped to the level where imported Harleys were too pricey for the market. H-D Japan’s head man, Alfred Childs, had a bold and daring idea: build a Harley factory in Japan.

This story must be true…no one would dare make up anything so outrageous.

Brian Blades

Now, the four founders of Harley-Davidson were still alive and active … and skeptical. Not even the Japanese had much faith, but Childs persisted and the deal finally was done: Harley would ship plans, tooling, blueprints, would loan some personnel and also build a factory in Japan, with one of the few restrictions being that the product would not be exported out of Japan.

The necessary investment capital came from Sankyo, and the plant was built next to that pharmaceutical giant’s headquarters at Shinagawa in Tokyo. According to Childs’ recollection years later, production began in 1929, and by 1935 the Shinagawa plant was building complete machines, assembled from parts made in Japan. Thus began the Japanese motorcycle industry.

According to accounts from the time, the H-D factory was the most modern production facility in the country, with engineers and investors coming from all over the nation to see how it was done.

But wait, there’s more.

Harley of Japan’s main product was the 1200cc … i.e., 74 cubic-inch … sidevalve Twin designated the V series and introduced in the U.S. late in 1929 as a 1930 model. In 1930, the Japanese version of the V was designated the official motorcycle of the Japanese army.

Then things got rough. The Japanese military took over the civil government and the new leaders didn’t like the H-D connection. At the same time, just as the Shinagawa plant went into full production, Milwaukee introduced the Model E, the overhead-valve Knucklehead which, in vastly improved form, is still with us. Milwaukee suggested Shinagawa convert from the old sidevalve 74 to the new ohv 61. Shinagawa demurred, on the grounds that the new model wasn’t yet proven and the old model was just what the main customer, the military, wanted.

They compromised. Sankyo took full control of the Shinagawa plant and changed the brand name to Rikuo, while Harley-Davidson’s Childs switched to importing and distributing the new Harleys.

Childs was a personable man who strongly believed in his project in Japan, but the war clouds were clearly on the horizon. He was also an astute businessman; and when a Japanese friend, a certain Col. Fujii, came around with an offer to buy the Harley operation, for gold, and suggested that Childs whisk his family aboard the next ship out, Childs said yes, twice.

(One more aside here: The popular translation of the name Rikuo, in English, is generally given as Road King—which would be neat, because 60 years later we have the current Road King. But it ain’t so. According to the best translators and a reading of history in Japanese, the name actually means Continent King and was taken from a Keio University song. Molding Continent King into Road King takes more imagination than the average poetic license permits.)

Back with history, World War II began for Japan with the invasion of China in 1937. The Rikuo had been designated Model 97 by this time, and the military’s demand for the rigs outdid Shinagawa’s supply. To meet that demand, Rikuo licensed a copy of its licensed copy, so to speak.

One of the suppliers was an outfit named Nihon Jidosha—or, in English, Japan Combustion Equipment Co. That company began building a variation of the Model 97 based on Harley’s 1935 VDDS, a version of the V series enlarged from 74 to 80 inches and offered in 1935 and 1936 because the Model E had been delayed and the sales department wanted something new.

This is all normal business practice, just as the Luger pistol was invented by an American but licensed to about 20 countries in Europe, resulting in all sorts of Lugers with no two exactly alike.

So, the Nihon Jidosha Model 97, therefore, was a variant of the Rikuo, which was a variant of the Harley V. The second-step motorcycle had its own name, Kurogano, or Kuro Hagane or Kurogano-Go, depending on when the translation was done; but in all three cases, it meant Black Iron. And that—apologies for having to present it in such a roundabout way—explains the bike we see here in all its splendid glory.

One Man’s History

How did this bike get here? With the onset of war, we naturally lose track of the Japanese side of history; so, join us in a major Fast-Forward—and a leap of faith bordering on the fantastic—as to how the bike was found in California.

The man who owns and has restored the Kurogano is Steve Rainbolt from San Diego, California. He’s the master of a variety of crafts, most of which came in handy with this project. Rainbolt’s veracity is beyond question; all he can do is tell us what he’s learned and what he’s been told. What he was told came from a former co-worker, the man who found the bike and from whom Rainbolt bought it.

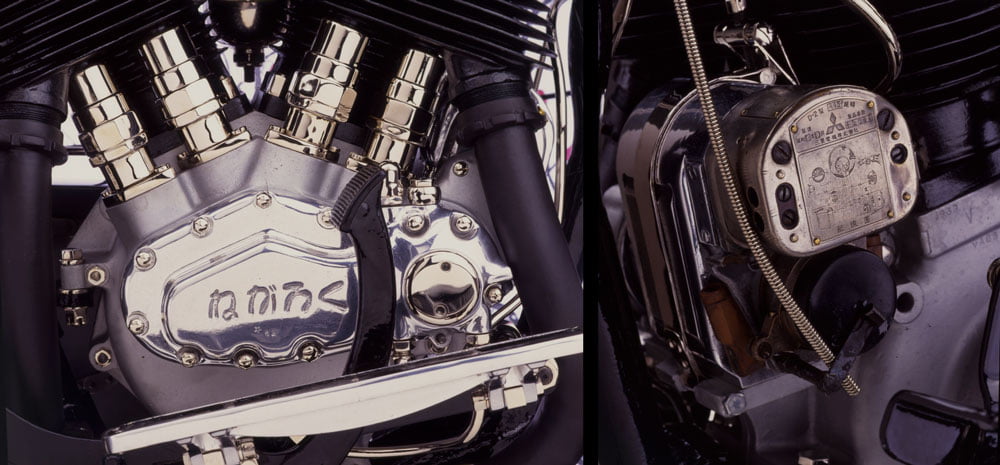

Reinforcing the fact that the Black Iron was, after all, a warhorse, a wiring schematic was etched into the magneto cover for quick reference just in case the operator’s manual got lost—which, in wartime, was almost inevitable. In Japanese, “Kurogano” looks like this (left).

Brian Blades

Rainbolt and the seller were pals at work. The other man knew that Rainbolt was interested in motorcycles, so one day, the guy mentioned that he had a really old and rare machine. How he got it, the story unfolded, goes back to 1963 when he and a friend were hunting deer in the remote mountains of Central California. The second hunter thought he saw a deer in the underbrush, so he fired. The bullet made an odd sound, so the men plunged into the thicket and found … a huge, old motorcycle. Kind of like a Harley, but not quite. They dragged it out and noticed what looked like Japanese characters on the gearcase cover. One sparkplug had been removed, and they guessed that the rider must have had trouble, hadn’t been able to fix or find the cause, and had abandoned the bike. Enough time had elapsed to let weeds and brush hide it from casual passersby, but it hadn’t been there long enough to rust away. By still another providential circumstance, the finder’s wife is Japanese, and she translated the characters to say Black Iron.

No one knows, of course, how this bike ended up being abandoned in the California mountains. But let’s use just a little imagination and move to shortly after the end of World War II and a guy who came into possession of spoils of war: a military motorcycle to which he had no title. One day, he rode his huge, old machine into the woods for some truly aerobic motocross, and when it broke, he left it there. Time passes. Then Rainbolt’s friend, accompanied by the sort of sorry sportsman who takes potshots at shapes he can’t identify, stumbles across the abandoned bike. The friend is a motorcycle nut and takes the bike home, where, by still another happy circumstance, there’s somebody who can read Japanese.

There’s a school of thought that says this story must be true, because no one would dare make up anything so outrageous.

In any event, Rainbolt’s buddy took the motorcycle home, dismantled it and, after taking pictures of the bike as found, began a half-hearted restoration. The finder said he asked around and was told it was a Japanese copy of a Harley-Davidson, made from old patterns and tooling that had been sold in secrecy by H-D’s owners.

Next problem for the meticulous restorer? Where to find documents. The plant where the motorcycle had been made was located in … Hiroshima. Yes, that Hiroshima, ground-zero for one of the two atomic bombs that ended the war. The plant, records and such were ionized, which is why there are no Kuroganos in the history books.

Black Iron Reborn

But never mind all that. How this giant orphan of a motorcycle got here isn’t as important as the fact that, first, it’s here, and second, what it is. Second part first.

Based on hearsay, trains of logic, Japanese history books, facts presented by friends who work for accessory firms and have other friends fluent in Japanese, some help from the Harley-Davidson archives and, most of all, a Rikuo history written by C.D. Bohon for Cycle World 20 years ago … what we have here is a quasi-licensed version of a 1934 Harley-Davidson VLH. It was made in 1939 by the Japan Combustion Equipment Co. for the Rikuo company and designated Model 97, named Kurogano—or Black Iron—and nicknamed Two Story.

The Two-Story moniker comes from the sheer height of the beast. When there isn’t much suspension at one end and none at the other, as is the case with this machine, and you need lots of ground clearance for military ventures, the only way you can get it is to mount the engine and gearbox and occupants way up there.

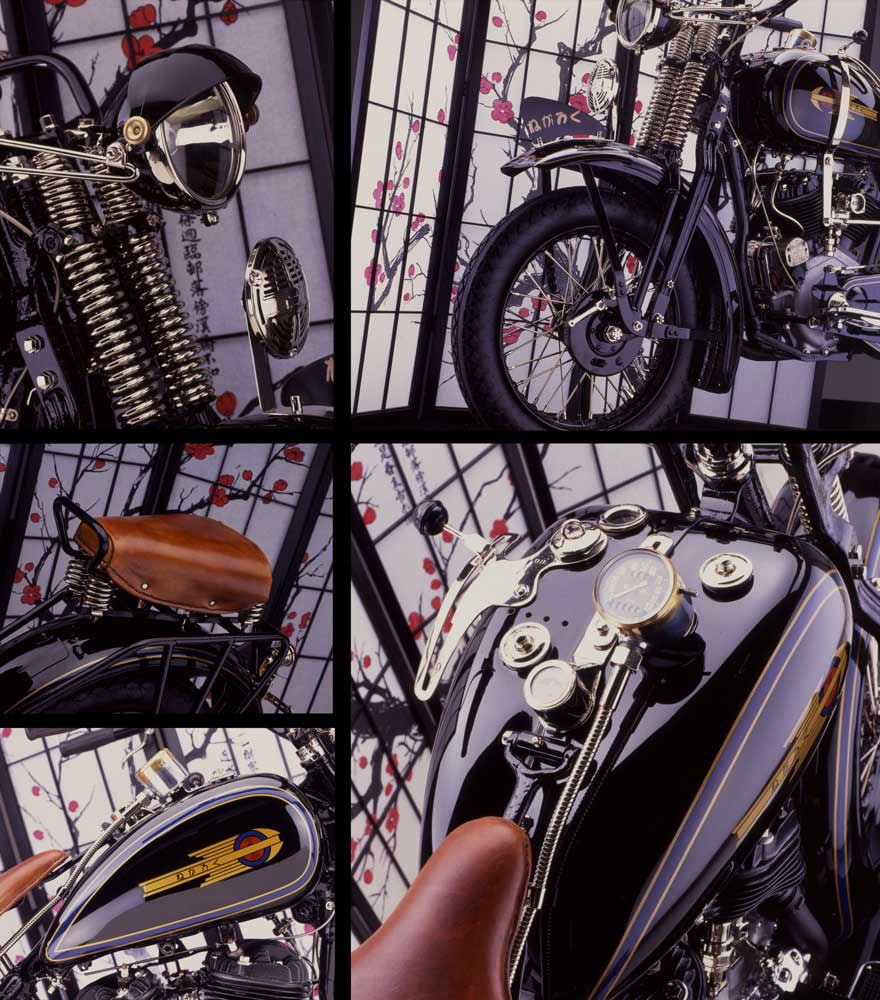

Kurogano’s engine is a sidevalve V-Twin with a 45-degree Vee-angle, and a bore and stroke as near to 3.42 by 4.25 inches as the Japanese Industrial Standard of measurements allowed. The gearbox has three forward speeds and one reverse, just like on the Harley sidecar transmission, but the Kurogano has a different shift pattern: Reverse-Neutral-Low-Second-High. The gearbox was sourced from a Japanese supplier, as was the combined magneto and generator. Shift is by the left hand and the clutch is by left foot, again, as with H-D. Oiling is by reservoir, with the supply carried in the saddle tanks. The rear wheel is rigidly mounted and the front wheel suspended, with leading links patterned after Harley forks; but the legs and linkages were done in Japan.

So were most of the cycle parts. The taillight is obviously not H-D, and the headlight came with a standard-military-issue shutter. The non-Harley fenders have trapdoors in the middle, which in other military motorcycles was done so the rider could scoop out mud that packed the fenders until the bike wouldn’t move. We lack the Model 97’s instruction manual but can assume these fender flaps are there for the same reason.

The Black Iron was a Springer long before springers were cool, and the pillion is heavily spring to compensate for the rigid rear end. The armadillo-style headlight shade was employed when the smoking and driving lamps were out so as not to attract trolling Hellcats, Lightnings or Spitfires.

Brian Blades

According to the specifications found in an old book, the Kurogano had an overall length of 99 inches, a wheelbase of 65 inches (compared with 59.5 inches for a ’36 Model E or 63 inches for an FLT) and a weight of 1100 pounds. The book shows the bike with sidecar, so one might presume that weight is for the complete outfit; but owner Rainbolt says that lifting the machine onto its stand indicates it weighs at least 1100 pounds as it is right now.

Rainbolt got quite a lot of help from a man who works under the name Stett, a Harley wrench with a shop in El Cajon, California. The restoration was a tremendous challenge. The parts were there, mostly, but they were worn and obscured. Rainbolt even had to painstakingly take impressions of the old rubber pads for the floorboards, then make molds and cast new pads.

Stett also discovered that the presumed Harley-Davidson copy had threads done to Japanese Industrial Standard. This was back when Yanks used inches, Brits had Whitworth, Yurrup was metric and the Japanese didn’t match any of the others. So, every time Stett tried to have the machine shop make a bearing race or shaft or whatever to Harley specs, it didn’t fit—not until it had been re-sized.

And sometimes they just improvised. See the badges on the tanks? Looks like the Art Deco design used by Harley-Davidson from 1936 through 1939, right? Look again. It’s got fewer feathers than the H-D emblem, and the symbols, which mean Black Iron, were done locally. The restorers admit they can’t prove that the bike came with such an emblem, but there’s no proof it didn’t, either.

Same for the paint. As found, blue stripes on the Kurogano were still visible, so Rainbolt found an expert who could analyze the faded patches and come up with the shade of blue that looked like new. But when the Model 97 was painted in the olive drab so loved by armies all around the world—the color of paint this machine had when new—it looked like baby poop. Rainbolt felt that dull, drab appearance justified him choosing the black-with-blue treatment you see here. The fact that the paint isn’t original drives restoration purists nuts … but then, it’s Rainbolt’s bike, and he can do with it whatever he damned well pleases. You have to admit, though, that the black-and-blue paint job is flat gorgeous.

What we see here isn’t the final product. For one thing, it doesn’t run. Yet. The magneto/generator came with a wiring diagram on the cover, but the new wiring loom hasn’t been finished. Stett has tried to use valves from Harley’s V engines, then the U engines, the W, the E and the F, but none quite fit. It can be done; it’s just a matter of welding the right tulip to the right stem. It just has not yet been done. But it will be.

Rainbolt took the Kurogano to the ’97 Del Mar show and came home with the Judges’ Choice trophy. Not bad for a bike that, by all the rules, shouldn’t be here at all.

It just proves that when fact out-fancies fiction, we’re all the better for it.