1937 Knucklehead – Wheels Through Time

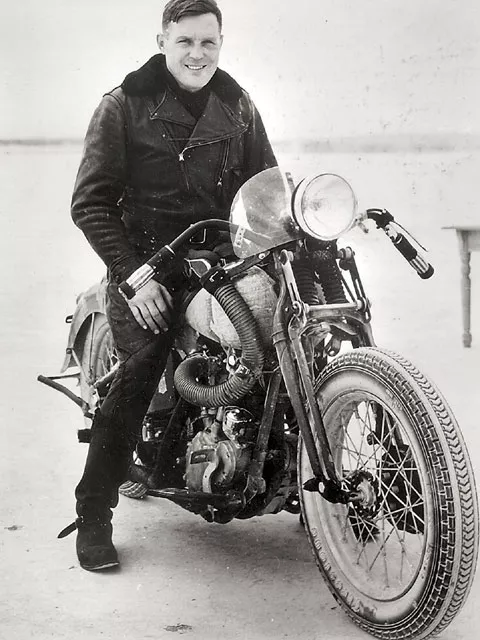

Fred Ham with his ’37 Knucklehead at Murdoc Dry Lake, CA, in 1937.

Fred and his pit crew. Add to that shortlist the name of Wayne Stanfield, who would seek not so much to best Fred Ham’s remarkable achievement but to pay homage to it. In doing so, he took up the challenge, just as Fred had all those years ago when he sought to surpass the previous record set by Wells Bennett aboard an Indian in 1922.

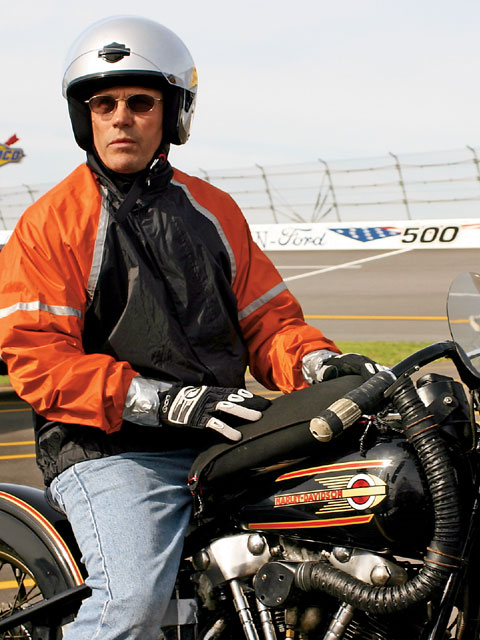

Wayne Stanfield with his ’37 Knucklehead at Talladega Superspeedway in 2007.

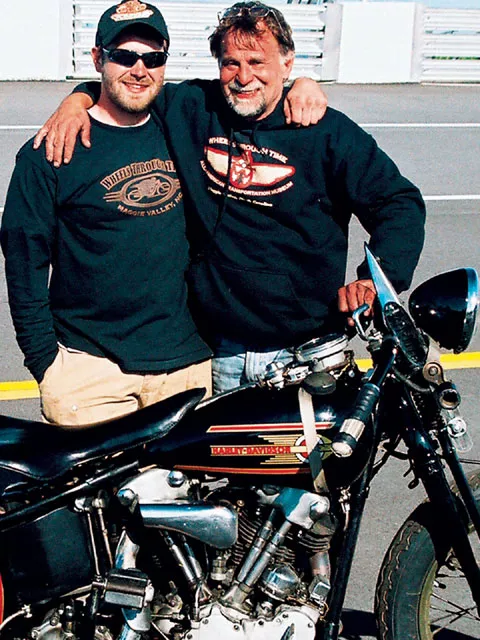

Dale Walksler and his ’37 Knucklehead.

Here, father and son Dale and Matt Walksler carry on the tradition…never give up! The engine was built from used ’37 cases, NOS flywheels and connecting rods, original four-fin cylinders, an NOS M-51 carb, and original timing gears and cam.

The ’37 WTT was bone stock except for a custom intake hose, Subaki rear chain, rear sets by Moe, and Avon tires.

Dale test-riding the ’37.

Fueling and fixing with no time to spare.

In 2007, the Wheels Through Time Talladega Endurance Challenge Pit Crew consisted of Dale Walksler, son Matt Walksler, Myron Pace, Brian Haelein, John Dills, Steve Beluski, Jon Swanson, Joey Crider, Garry Michael, Joe Brown, Mike Edwards, Brice Cooper, Jim Usher, and Carl Lathrop.

Several layers of clothing helped in the freezing temperatures.

Go for it!

Wayne at speed.

On the last lap…time running out. While the Fred Ham record of 1,825 still stands, the WTT ’37 Knuckle racked up 1,350 hours despite six hours of downtime.

The venerable and much-loved Harley-Davidson Knucklehead commenced production in 1936 and lasted into 1947. For H-D, it represented a revolutionary leap forward, as it featured the company’s first engine with a recirculating oil system.

Yes, hand-shifting a three-speed tranny!

Featuring what is considered the finest display of American motorcycles from 1903 through the present, the Wheels Through Time Museum is a gathering place for bike fans from around the world. In addition to more than 250 motorcycles and dozens of rare cars, the museum offers over 25,000 examples of historical memorabilia and has attracted more than 250,000 visitors to its idyllic Maggie Valley, NC, location.

It was on a hot Thursday morning that an athletic six-footer named Fred Ham climbed aboard his ’37 Knucklehead, the seat sizzling from the sun beating down on Murdoc Dry Lake, California’s answer to Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats. No traffic lights-no traffic, in fact, would get in his way this day. He would be riding in a dusty circle 5 miles in diameter, around and around, and by the end of 24 grueling hours, Fred and his ’37 EL would clock 1,825.2 miles averaging 76.62 mph. That date was April 8, 1937, and the record had never been challenged…until almost exactly 70 years later, when on Wednesday, April 4, 2007, at precisely 4:40 p.m. Wayne Stanfield climbed aboard a 61ci OHV ’37 Knucklehead, a nearly exact replica of Fred Ham’s bike, and started the stopwatch ticking and the twin cylinders churning. It would be an attempt to have history repeat itself…and then some.

Back in 1937, Fred, a motorcycle patrolman by profession and a motorcycle record-breaker by inclination, had previously won the famous Big Bear Enduro and held the Three Flags Canada to Mexico endurance record. On April 8, flaming pots illuminated the rough circle marked out in the parched earth, just enough to keep him on track as the sun set and the 100-degree heat plummeted to near-freezing temperatures. Fred rode on into the darkness, both he and his Harley-Davidson seemingly impervious to the relentless pace. Like that other famous endurance rider, Ed Kretz, the term “Ironman” certainly applied here.

Wayne Stanfield brought with him some rightfully earned credentials of his own. In 1995, he rode a ’37 Harley in the Great American Race from Ottawa to Mexico City, the only motorcycle competing in that transcontinental event, where he finished fifth out of 95 entries. In 1996, he entered the event again, this time riding a ’36 pre-production experimental Flathead “80” from Tacoma to Toronto, crossing the finish line only one second behind the winning automobile. In 1997, Wayne changed mounts and directions, this time setting a cross-country record on a 1917 Indian riding from Los Angeles to New York in six days, 11 hours, breaking the old record by more than 30 hours. You could say that Wayne, like Fred before him, has “the right stuff.”

He also had the right motorcycles and partner in these efforts. That would be Dale Walksler, founder and curator of the Wheels Through Time Museum, home to some 250 classic, vintage, and antique motorcycles, including a small herd of famous race bikes. Also known as the “Museum That Runs,” the Maggie Valley, NC, facility also prepared the ’37 Knucklehead for the celebration of the 70th Anniversary of Fred Ham’s Endurance Ride. Dale and Wayne met a dozen years ago while competing against each other in the Great American Race and found themselves kindred spirits. Therefore, it seemed the most natural thing in the world for them to team up to write new pages in the history books. “Dale and I talked about making a run at Ham’s record over 10 years ago, and I said sure. It wasn’t until a year ago that I realized he was serious, partly because I never thought he could get that track.”

How serious? For the attempt at the endurance record, Dale, as crew chief and lead mechanic, built a ’37 Knucklehead as close to Fred Ham’s ride as possible. Fred’s EL, basically a stock bike, had been prepared by tuner Bill Graves, who had polished the cases, piston rod, and crankshaft to reduce friction. Besides a small windscreen and a carburetor induction tube to block the abrasive Murdoc Dry Lake debris, the bike was unmodified-and deliberately so, since it needed to show the world what Harley-Davidson had to offer.

Says Dale about his re-creation of the ’37 Knuckle, “It’s all Harley-Davidson. I polished the internal parts just as Graves did, but that’s it. The only differences are the enclosed chain and the tires. There are no non-stock high-performance parts.” Fittingly enough, the Knuckle was finished on Christmas Day 2006, a “present” for the museum’s already stellar collection of historic American iron.

Speaking prior to the record attempt, Dale added, “Fred was one of the greatest endurance riders, and no one will ever surpass his feat at Murdoc Dry Lake. Besides, that was then, and this now. He was on a hard dirt surface, and we are on a paved superspeedway. And although we’ve tried to duplicate his motorcycle in mechanical detail, it’s a fact that lubricants and tires are far superior today. All of these factors will give us an advantage. Our effort is to honor Fred Ham, to celebrate his accomplishment, to prove what a fine motorcycle the Harley Knucklehead was and still is, and to publicize the unique nature of Wheels Through Time among America’s leading motorcycle museums.”

As far as physically preparing for the endurance challenge, Dale and Wayne were well-informed about Fred Ham’s regimen back in 1937. Swimming daily at the local YMCA, he shaved off 30 pounds, trimming down to 180. Coincidentally, Wayne’s weight matched Fred’s almost to the ounce. Much of the prep work was mental. “I knew what it took to make this kind of ride. I went to bed at midnight and got up at 4:30 a.m., learning to function with the minimum of sleep, as well as adjusting my diet to improve my mental and physical stamina.” In spite of their many similarities of experience and abilities, there was one major difference in their stats: Fred had been 29 when he did his 24 hours. Wayne was 59. Of course, age is a relative thing, and Wayne wouldn’t even consider it a factor.

The plan was to have pit stops every 90 minutes for refueling and servicing, but no cat naps were included. It would be 24 hours nonstop-and not around a circle inscribed in the ground. The challenge would take place at no less than the legendary Talladega Superspeedway in Lincoln, AL. The track, about to celebrate its own 40th anniversary, measures a 2.66-mile oval complete with high banked turns up to 33 degrees. Its three straights see speeds “well in excess of 200 mph,” as clocked by NASCAR competitors. The largest oval track in the Nextel Cup Series, it has seating for more than 175,000. On this day the stands stood empty, the entire track turned over to Dale and Wayne and the Wheels Through Time crew.

Fate dropped the hammer almost from the start, as a series of challenges faced the intrepid challengers. After the first few laps, Wayne and the Knuckle rumbled back to the pits, with the Wheels Through Time crew gathering ’round. Something was apparently amiss with the ignition timing and carb. Oddly enough, Fred Ham and his bike lost an hour of downtime back in the day when a stretched primary chain had caused some damage. In Wayne’s case, the delay was 45 minutes, and then the electrical gremlins were resolved and Wayne was back in the saddle. But then on Lap 18, he was back with a more serious problem: The bike was losing power. “At this point, I realized the motorcycle was on the brink of disaster,” said Dale. “Then I heard Wayne say, ‘well, can we fix it?'”

Now, Dale is not one known to flinch in the face of disaster, so he got right down to solving the problem, even though it turned out to be a major one: a burnt piston on the rear cylinder. “Everybody hunkered down and worked together,” said Dale. “We transplanted the entire cylinder and piston from my spare bike, with the whole ordeal lasting about 65 minutes. It was back on the track, running like new, Wayne nailing the throttle WFO the rest of the night.”

It was nearly 9 a.m., and he was facing an icy headwind and deepening darkness, but Wayne managed to shave a second and a half each lap, the bike performing flawlessly throughout the night, averaging 82-87 mph. “It got dicey on the track at night, not much light coming from the bike’s 6-volt headlamp,” Wayne told us. There was only one rear tire change, at around 2:30 a.m., and the Knuckleduster was back kicking asphalt. “I would have ridden the tire bald,” said Wayne, “but Dale was always looking out for me to make sure everything was as safe as it could be.”

Three hours later, the sun peeked over the horizon, long shadows stretching across the track, the chill finally fading from the air. Wayne and the Knuckle were now at full stride, the bike hitting between 90-104 mph, lap after lap, although the headwind slowed him down to 80 in the straightaways. A 10 a.m. pit stop to replace a worn-out primary chain took just 15 minutes.

When asked by some of the younger crew members who the backup rider was to spell him if he needed it, Wayne replied, “I’ll only need a backup rider if I fall off.” There was no falling off and no backup rider, despite the fact that before going to Talladega, he had only ridden the bike on the street, and that time from Jacksonville, FL, to Birmingham, AL. To get somewhat familiar with the track, he did take a few laps around it on a new BMW dual sport. “I didn’t have much experience with the bike going into it, but by the end of the day I had plenty.”

Besides bucking a headwind the entire time (along with ambient temperatures that hit 32 degrees F, not counting the wind-chill factor at 85-plus mph), Wayne had to deal with the ergonomic backlash from more than 18 hours in the saddle (six hours were lost to repairs, pit stops, and fuel-ups).”My hands felt the size of a telephone pole halfway through the night, and because I had to keep lifting my head over the windscreen, after a while it felt like there was a large screw being driven into my neck. But I have to say it was the most painful fun I’ve ever had.”

Summing up the attempt to break the record that fell short due to mechanical downtime, Wayne says, “While we didn’t beat the record, we had a great run and did it on a 70-year-old bike. It was also the first car or bike to run 24 hours at Talladega, as well as clocking the most consecutive laps and most miles in 24 hours. I know Dale is proud of the fact that the bike made it, and I am as well. It was a combination of a great crew and a great bike, plus Dale with his drive, spirit, and talent making it all happen.”

Asked what would happen if Dale Walksler called him on the phone and said, “Hey, Wayne, wanta go back to Talladega?” Wayne smiled and said, “In a heartbeat. Absolutely. I’d be ready to go tomorrow.”

If this saga of courage and endurance got your adrenaline pumping and mind humming with “what ifs?,” then you’ll be happy to hear that Wheels Through Time is considering issuing a challenge to a number of four-man teams to approach or surpass Ham’s record. Said Dale, “Perhaps a $200,000 purse will entice new talent in 2008.”

For more information about Wheels Through Time Museum, its calendar of events, and its online television series, including video of the endurance record attempt, log on to www.wttthetimemachine.com, or call (828) 926-6266.