Micromachines: Archive

Since Harley-Davidson announced its new line of 750 and 500cc Street lightweights to the world, reactions were mixed, to say the least. Like that old set of tats on a biker’s hairy knuckles, it’s either love or hate.

Personally, I love it. Japan’s had its sights on Harley’s target market (read: Big Twin) for quite some time. It’s high time H-D repaid the favor with a light cruiser entry that hits foreign manufacturers where they’re traditionally dominant. What I don’t like is how some people look at the Street and say, “Oh, hell no. That’s not a Harley.” There have been a fair number of small hogs in the 110-year life of The Motor Company. Not just in its childhood, either. Here’s a brief history of those sub-883cc Harleys through the years.

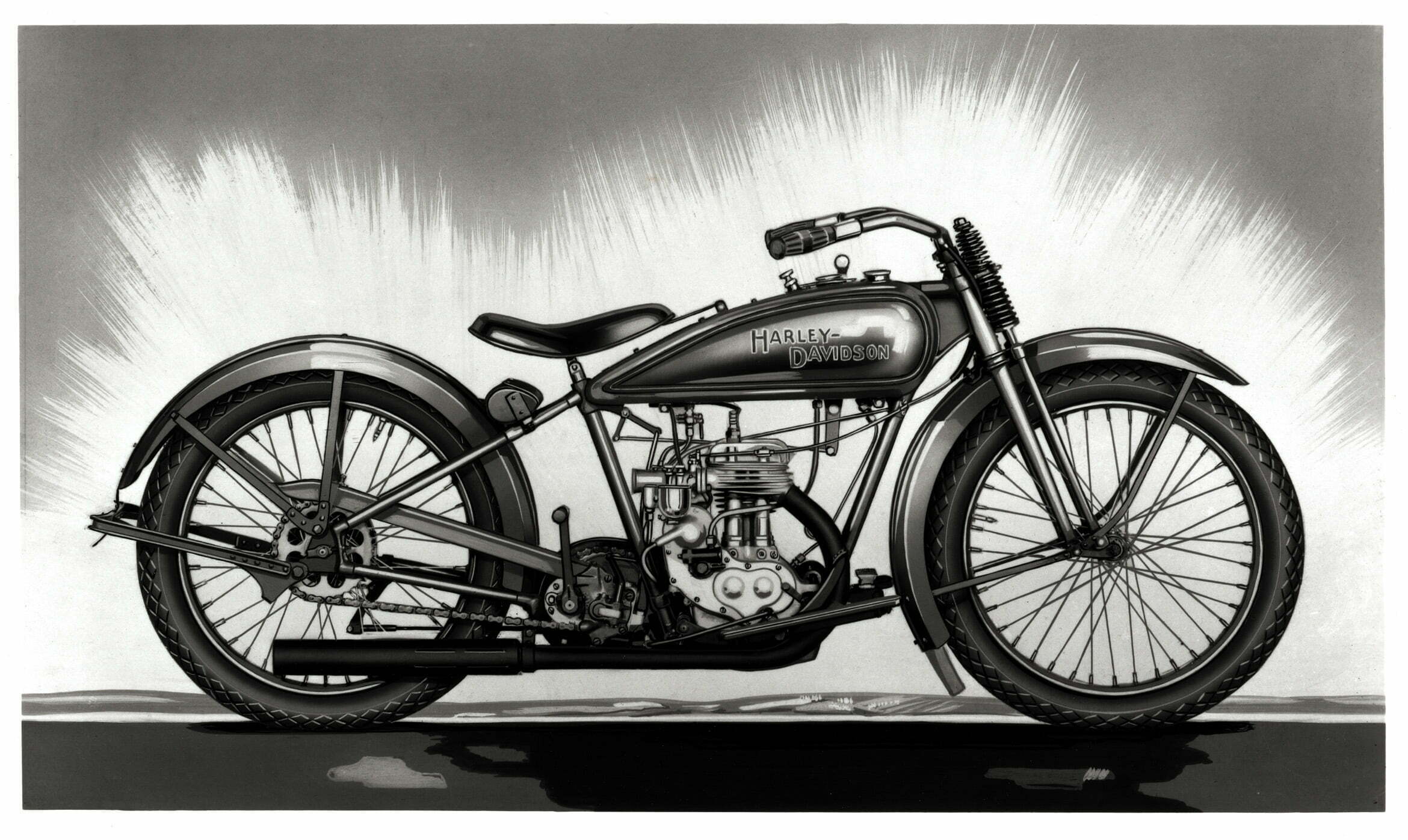

Harley’s 1926 single-barreled scoot.

Words: Mark Masker, Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

Living Single

Seeing as how Harley-Davidson originally wanted to make motor-powered bicycles, it’s no great shock that the first model the company produced was a tad on the small-displacement side. Its single-cylinder motor had an atmospheric valve control and a leather belt drive. Harley didn’t start making V-twins until 1909. By modern standards, it was no beast in the displacement either—just 49.5ci.

Harley made single-cylinder F-head engine bikes until 1918. It wasn’t until 1926 when the company brought back the single-cylinder motor with the A- and B-series scoots powered by a one-cylinder Flathead mill, three years before The Motor Company’s bigger (and better known) V-twin flattie hit the market.

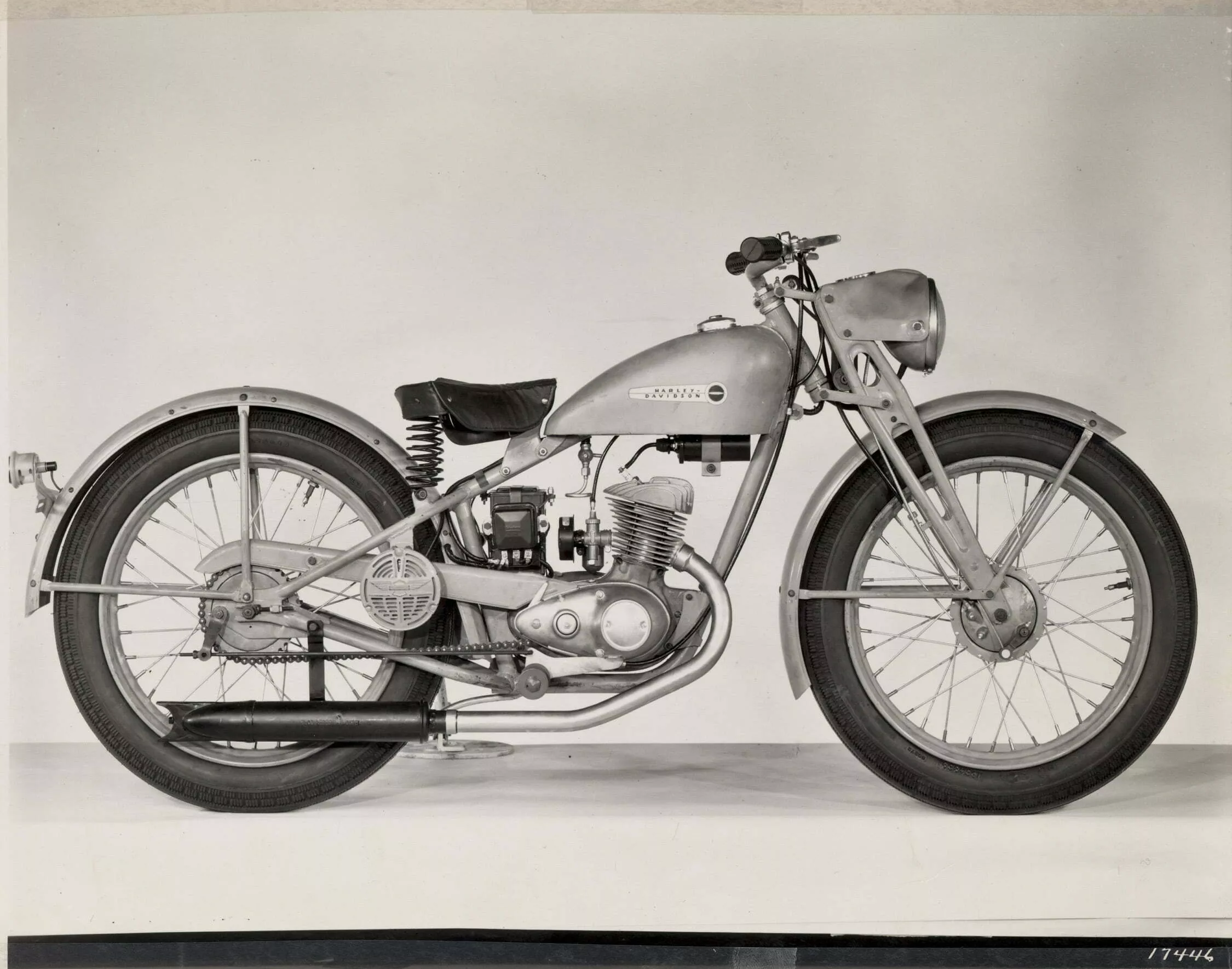

The 1948 Model S.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

The Post-War Era: Who Wants a Hummer?

American demand for lighter iron following the Allied ass kicking of 1945 is well documented. What isn’t so talked about is Harley’s response to that on the tiny end of the scale. Nostalgia makes us focus on the Big Twins of the 1950s, but in 1948, Harley surprised the market with its new model S motorcycle. Rumor has it the motorcycle was based on Germany’s DKW RT125, the drawings for which were taken from Germany as part of war reparations after World War II. The Soviet Union and UK made their own RT125-based bikes—the Minsk and BSA’s Bantam, respectively. Harley’s 125cc model S sold at a MSRP of $325. For just $7.50 more, you could even get it with chrome rims. Its single-cylinder engine made a whopping 3 brake horsepower (bhp). That might not sound like anything to brag about, but we’re talking about a motorcycle that weighed 200 pounds. Those 3 horses got the S up to around 55 mph.

It wasn’t until 1954 that the model S got the name most people know it by: the Hummer. And who among us doesn’t like a Hummer, am I right? European competition in the small-bike market grew fiercer every year, and Harley kept pace with improvements to the little bike to match. After the Hydra Glide fork came out for Big Twins in 1949, the 125 got its own telescopic forks and was renamed the Tele Glide. Later, the Hummer’s motor grew to 165cc. Sales in the 1950s were great.

By 1960, the little bikes made up to 9 bhp (though a 5 bhp version was made for the American market due to power restrictions on bikes available to young riders). Sales were good enough to support a whole line of these featherweights; the 1962 model year included the Scat, Pacer, and Ranger versions. The 1963 versions even had springs beneath the engine, making it a bit of a precursor the Softail frame.

Harley stopped making Hummers in 1966. The 18-year-old platform was just too out of date to keep pace with its competitors. Six years prior, though, H-D laid the foundation for the Hummer’s replacement by buying 50 percent interest in a little Italian company named Aeronautica Macchi.

Harley bought into Aeronautica Macchi because it wanted a bigger piece of the lightweight-bike action enjoyed by H-D’s foreign competitors. Aermacchi, as the company came to be known, already made single-cylinder two- and four-strokers. Harley’s Hummers just couldn’t keep up with the British and Japanese offerings. Buying interest in Aermacchi gave Harley the tools it needed to compete.

Just a year later, Harley introduced its 250cc Sprint to the world. It was a homely little cuss, but success on the track made it popular nonetheless. It was an OHV single slung horizontally in its frame and made 18 hp at 6,500 rpm. By the time Kel Carruthers raced his 350 Sprint to a second-place finish at the Isle of Mann TT in ’69, his bike made 42 ponies at 9,000 rpm.

People didn’t just run Sprints on the pavement. Dual-sport versions for in and out of the dirt followed, including the Sprint H with a smaller gas tank, high front fender, and smaller seat. Later the Sprint H evolved into the Scrambler and, finally, Sprint SS. Aermacchi worked with Harley until 1978 when Cagiva bought Aermacchi. That was also the last year Harley’s SX 250 model exited the product line. It was the last civilian single offered by Harley until Buell’s Blast in 1999.

Speaking of Which…

World War II’s end didn’t finish Harley’s involvement with the US military. The manufacturer not only made WLAs, but it later made the XLA (military Sportster). While I’ve never heard of a Sprint-based Army bike, I do know Harley produced the MT350/MT500 machines for the military, in conjunction with the Rotax Company. Right around 1987, Harley bought military bike production from Armstrong-CCM. Production of Harley-Davidson military motorcycles ended with the discontinuation of the MT motorcycles in 1998.

When Harley/Buell introduced the Blast a year later, it received pretty good reviews. It was a fun little bike, easy to ride, with a neutral riding position similar to a scooter. The Blast was all part of H-D’s master plan to bring in new riders. The other half of that scheme was the Rider’s Edge Academy of Motorcycling, a beginner’s rider course available through Harley-Davidson and Buell dealerships.

Taking it to the street.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

Streets of Fire

Which brings us to now, more or less. The Blast went away before Buell closed its doors, but Harley’s desire for new riders didn’t. Between gas prices getting high enough to justify a reach around at the pump and pressure for water-cooled motors, it only makes sense Harley-Davidson would want a piece of the growing market of riders looking for modern tech and fuel economy in their daily cruisers. Some people might not like it, but, hey, not all bikes are for all people. As for me, I’d love to see Indian step up with a modern, small to midsize Scout to compete.

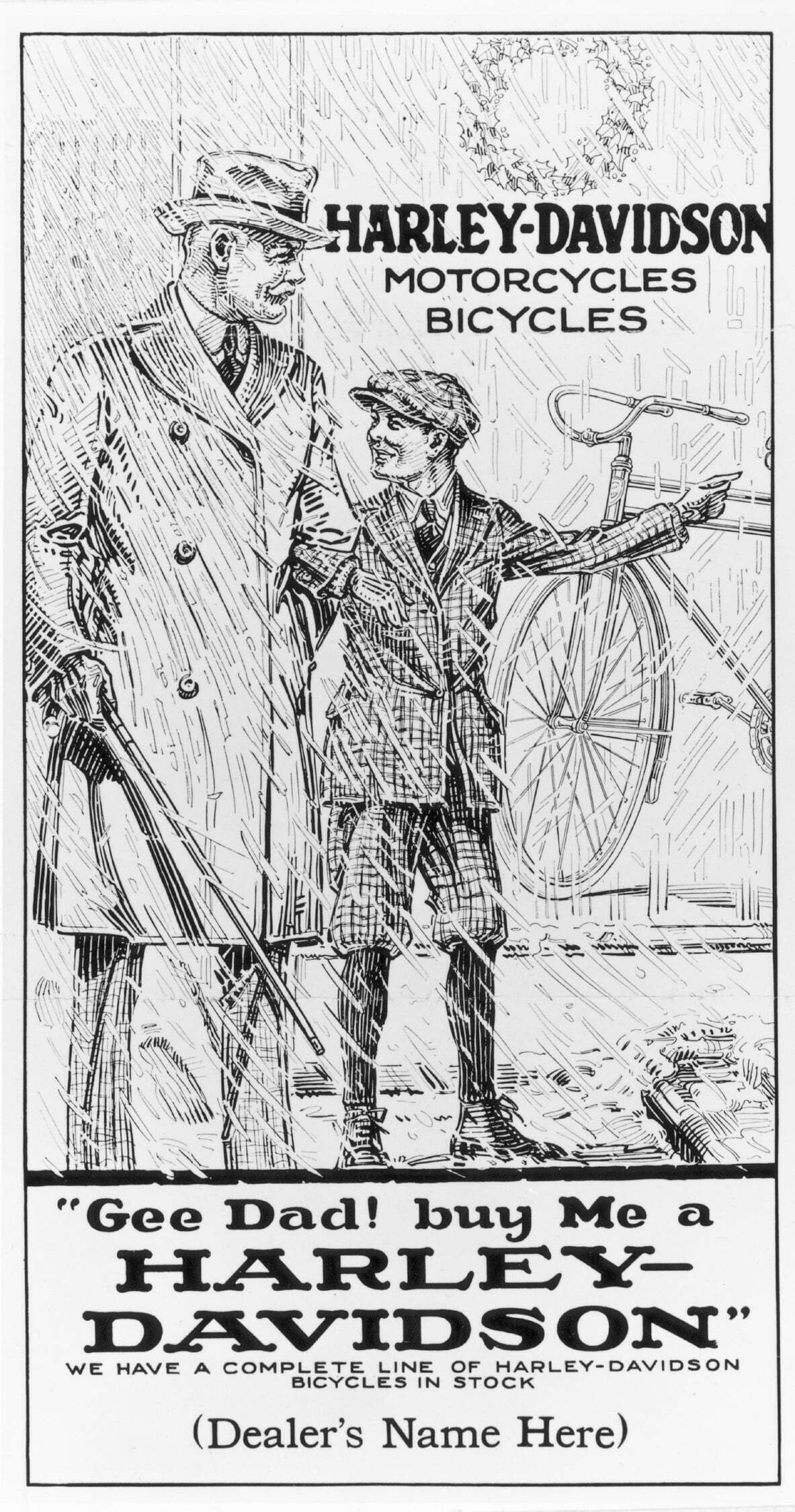

In 1917, Harley-Davidson started selling bicycles. The Davis Sewing Machine Company of Dayton, Ohio, made the components. At zero cubic inches, (i.e., no motor at all), I’m guessing this is the lowest-displacement production H-D ever made.

Words: Mark Masker, Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

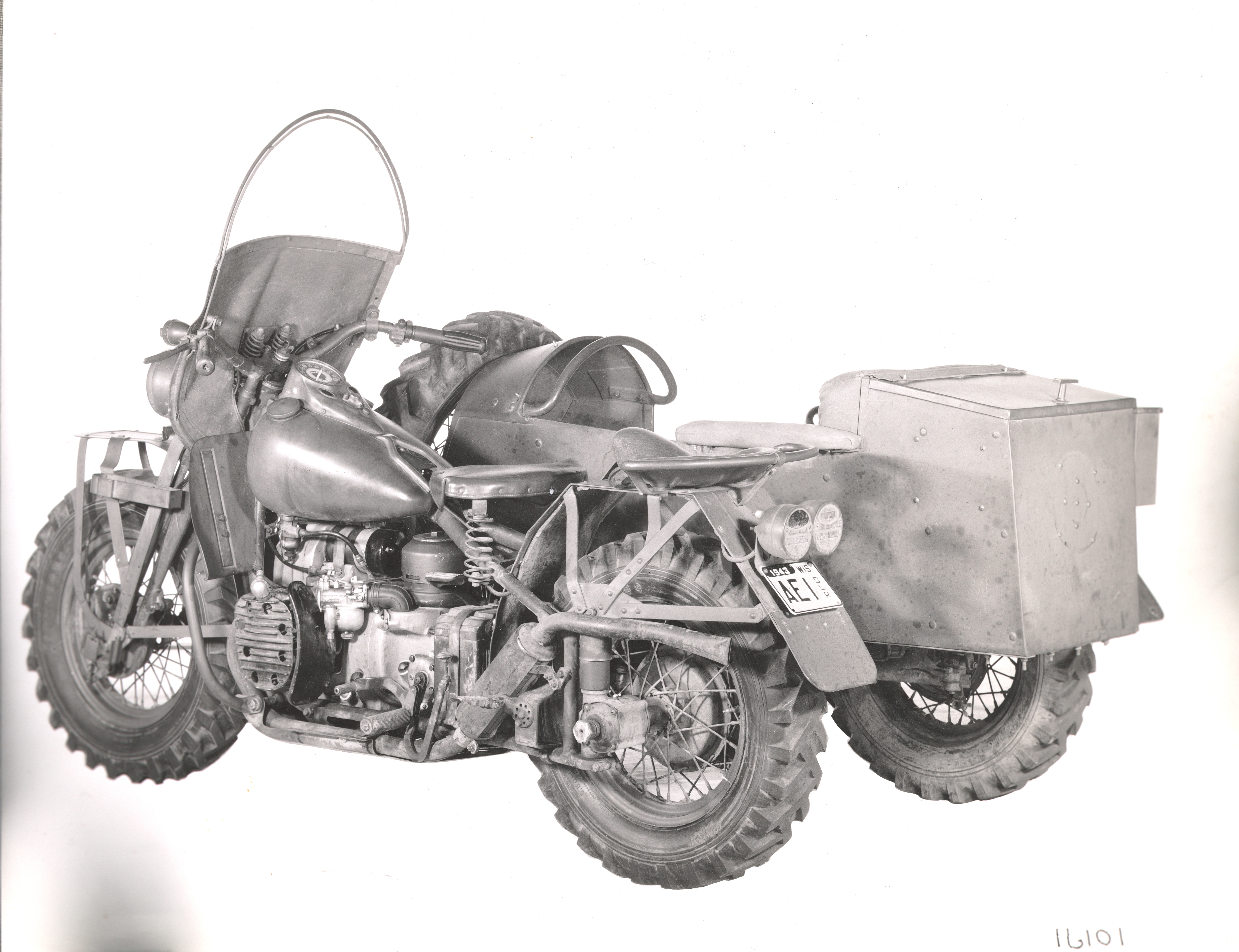

XS-ively Rare: Harley’s archives got its mitts on this ultra-rare, all-original XS model, complete with sidecar. What the bloody hell is an XS, you ask? It’s the sidecar version of Harley’s 750cc XA. The US government asked Harley to make a bike for desert warfare in North Africa. It responded with the transverse-engine, shaft-driven XA. The bike had a lot in common with BMWs of the time. The XA was designed for better cooling and durability in the unforgiving conditions found in desert riding. Only 1,011 XAs were built. None ever saw combat. The military canceled the order because the war had shifted to Europe by that time.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

Baby Salt Shaker: In 1965, George Roeder shattered Class A and C land speed records in a streamliner powered by a 250cc Sprint CR racing engine, averaging 177 mph.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

The Topper: Harley made a scooter. There, I said it. With Cushman and Vespa scooters pulling in sales in the 1950s, Harley stuck its toe in the scooter market with the 165cc Topper. Powered by a single-cylinder two-stroke engine mounted horizontally between the floorboards, its starter was a rope-coil like you’d find on a lawn mower. In 1959, a Topper was ridden from Bakersfield, California, to Death Valley and back without repair or any adjustments that required tools.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson