Two Builders Give Milwaukee Iron Some Santa Cruz Style

Mike James’ Road Glide is more radical than the customs built by Bruce Canepa, but all of their handiwork follows the same theme: bikes that from a distance look fairly stock, but that have had every single facet somehow altered or fine-tuned to achieve virtual perfection.

Ron Perry and Jeff Allen

This article was originally published in the December-January 1999 issue of Cycle World’s Big Twin magazine.

Surfers, the beach and the Boardwalk. That’s what Santa Cruz, California, is famous for. Until now. Thanks to a pair of local bike builders, Mike James and Bruce Canepa, Santa Cruz just might become equally famous as the source of some of the most stunning custom Harleys found anywhere. James and Canepa are turning Milwaukee iron into their own version of California cool, a subtle but sensational look you might call “Santa Cruz Style.”

James, a former computer- and publishing-company executive, recently opened one of the biggest Harley-Davidson dealerships on the entire West Coast. He also operates the only stand-alone Buell dealership in the world, just a few blocks from the Boardwalk.

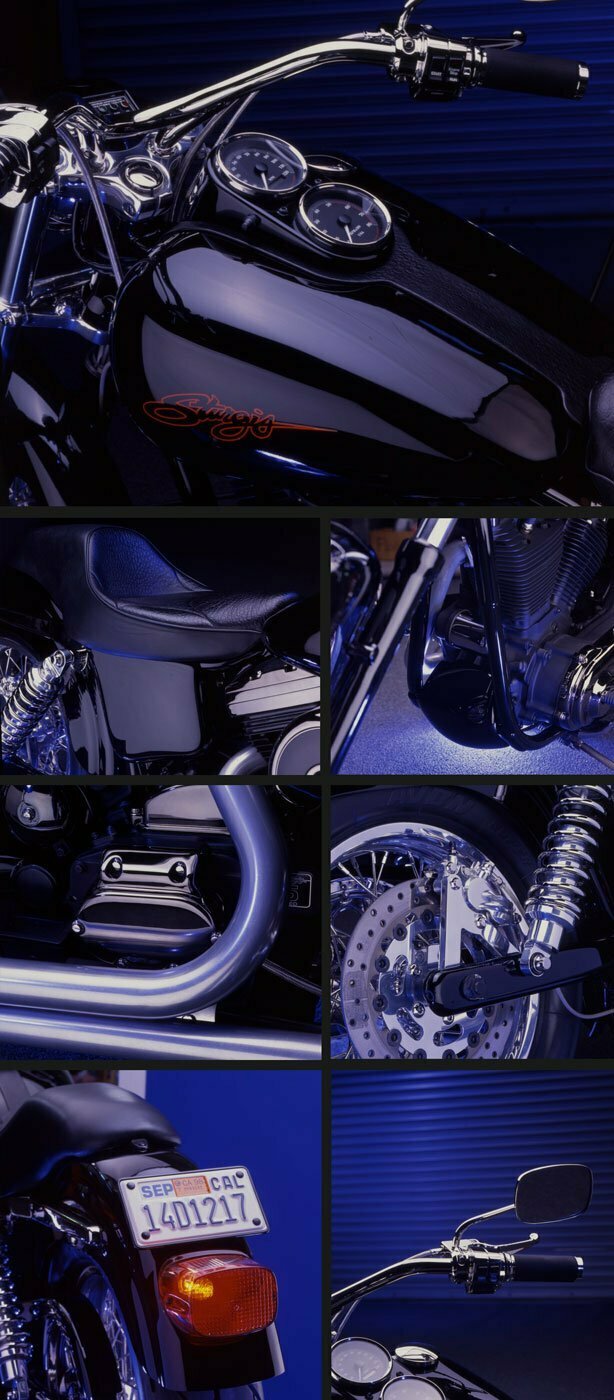

Fine-tuned details of James’ Road Glide

Ron Perry and Jeff Allen

After years of being buried in legal publishing, James saw the chance to create custom bikes as a much-needed breath of fresh ocean air. He plans to build several every year, and the Road Glide seen here is the first. It’s a bike built for the boardwalk—and for the boulevard and the blue-sky highway. Thousands of miles have passed beneath the Road Glide since James and his very capable Santa Cruz H-D crew finished the machine a few months ago. And like its name implies, this bike is built to be as easy on the gluteus maximus as it is on the eyes. It served well as Mr. & Mrs. James’ tour mule on a 5000-mile ride to and from Harley’s 95th anniversary party in Milwaukee—a trip on which they studiously avoided the interstates.

But despite the fact that this bike was built rugged and functional enough to make good time on rutted, bumpy, curving backroads, it also was meant to excel when simply standing still. James is proud of the unusual angles of the fairing and bodywork, and points out the absence of pinstripes and other distracting detail.

As evidenced by his Sturgis (above) and his Fat Boy, Bruce Canepa doesn’t try to build customs that are complete remakes of stock Harleys; he instead perfects the execution of the original design.

Ron Perry and Jeff Allen

Distractions—or, more to the point, their elimination—are an important concern for James. So, things such as the footboards, the turnsignals and several utilitarian brackets have been blacked-out by strategic applications of black paint, rather than glorified with triple chrome.

The Road Glide’s unique front fender is another perfect example of Santa Cruz Style. The heavy stock fender was junked in favor of a new, all-steel replacement fabricated to follow the contours of the 18-inch front wheel now fitted. To further lighten the front end, the right-side brake disc and its accompanying caliper were removed, and all the stopping duties transferred to a 13-inch rotor and six-piston PM caliper. The right fork leg was then ground and polished to remove all traces of the caliper mounts.

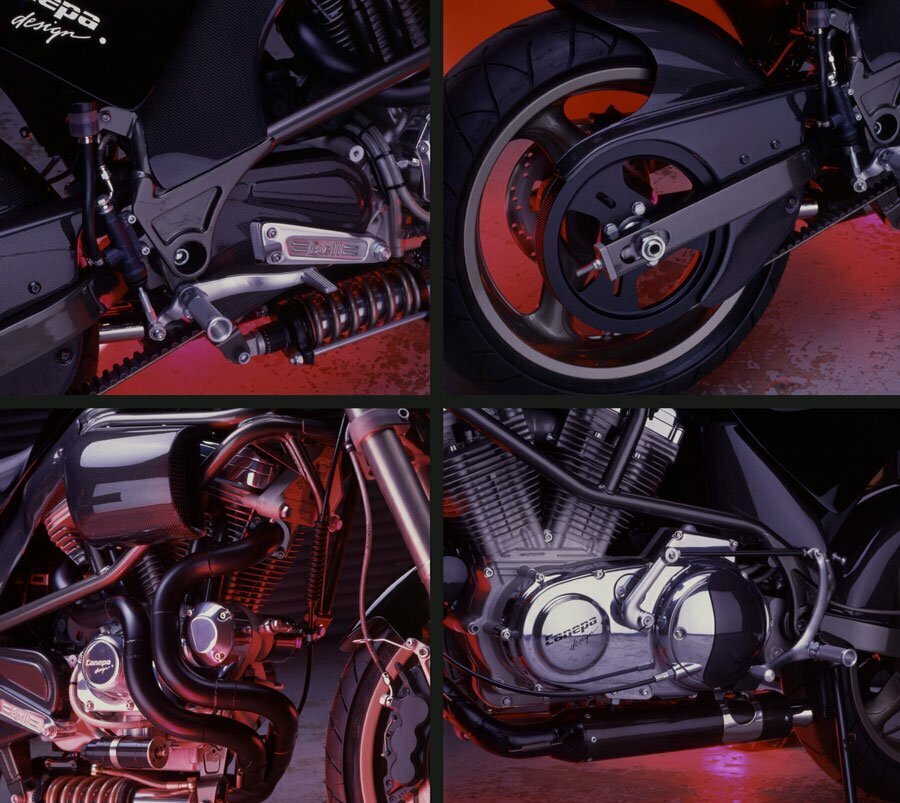

A collection of the details on Canepa’s Sturgis

Ron Perry and Jeff Allen

A wonderful contrast to the subtle look of the chassis is found in the bike’s amazing leatherwork. For all the thousands of dollars that builders spend on their bikes, most usually rely on the same basic aftermarket saddle. But not James. Working in cahoots with an old-style leather craftsman, he designed a seat that resembles a western saddle, complete with pommel for the pillion passenger. The raised pommel between the seats makes for a natural “grab rail.” Who needs it? Well, when the Tour-Pak and bags are removed for around-town riding, it’s nice to give your passenger something to hang onto.

Across the street from James’ shop, nestled behind the palm trees in a series of nondescript buildings, works his friend Canepa, a design guru who has been sending dream machines down the blue highways for three decades. But only recently has this sultan of style begun delving into the world of motorcycles. Before that, he worked his fabrication magic on just about anything else that had wheels, including trucks, trailers, semi-trailer transporters and, of course, cars.

Canepa’s Harley Fat Boy

Ron Perry and Jeff Allen

But not just your everyday, run-of-the-mill cars. Canepa lifts the hood and shows the heart of a V-Eight, twin-turbo, Ferrari-engined Lancia LT2 that qualified on the pole at LeMans in 1984 and ’85. His shop has rescued the retired racer from obscurity and neglect, restoring every moving part back to original condition—good enough to race again at LeMans tomorrow. “If you’re going to vintage-race classic cars, they should be able to go just as fast as ever,” says Canepa. So, by the time his crew has finished a typical 4000-man-hour, ground-up restoration of a Ferrari, a Lancia or a Porsche, the car is ready to take the starter’s flag in exactly the same condition as it was when new.

When you’re accustomed to that kind of operation, motorcycle customizing is practically a hobby, although an extremely serious one. Canepa’s two-wheel creations qualify as priceless works of art: works of art because they repay serious study, priceless because they’re not for sale. “If I sold one,” he asks, “what would I ride?”

Canepa first got involved with motorcycles back in the early Seventies. “I was doing custom paintwork and did some bikes back then. But I didn’t really get into them until 1991. That’s when Harley came out with the Dyna chassis on the all-black Sturgis. Then, I bought one.”

Close ups on some of the shiny parts of Canepa’s Fat Boy.

Ron Perry and Jeff Allen

And he decided to make “a few” changes. “The Sturgis took about 1500 hours,” he recalls. “I hated everything I looked at in catalogs, so we just made whatever we wanted. I kept the black theme of the Sturgis, except everything that the factory had done in gloss black paint we redid in black chrome. I designed the new parts, since I have a full shop that handles fabrication to the highest auto-racing standards.”

Canepa is a man who clearly takes pride in being different. “The norm in customs is factory bikes with lots of chrome bolted on, or custom bikes that have low, long gas tanks, long fenders and real wild paint jobs. But my bikes are not like that. They’re real subtle, real clean and they don’t have marine life painted all over. When these bikes go somewhere, they stand out. At shows, the Sturgis won every time. Obviously, everyone else liked that look, too.”

For confirmation of those claims, check out the Sturgis’ swingarm. Now an oval-tube design, it looks like it came from an Italian sportbike. But it’s a Santa Cruz-made. “The stocker looks like something from a blacksmith’s shop,” he says. “I wanted chrome-moly oval tubing. But you can’t buy chrome-moly oval tubing; so instead we took flat chrome-moly plate, folded it and milled off two halves, welded it together and made our own tube. We built a fixture to make the curve of the swingarm gradual instead of the factory bend, then milled up an end cap and finished it so you can’t see a joint.

Canepa’s Buell Lightning

Ron Perry and Jeff Allen

“We did the same with the battery, which sticks way out of the side and hits your leg. It’s uncomfortable. So, we put two small batteries in the bike, made a new sidecover out of aluminum, and hid the batteries and the electrics. That really helped the form of the bike. I like to see the engine, hate to see electrical wiring, plumbing and cables hanging.”

In true hot-rod style, messy but essential parts are hidden. There is no master cylinder, for instance, on the Sturgis’ handlebar; a brake cable is routed through the frame, back to a master cylinder under the swingarm. Then the hydraulics go back to the front, again through the frame. All fittings, of course, are stainless braided. “We started using Goodridge fittings before they were fashionable,” he claims.

Now turn your attention to the beefier fork. Canepa replaced the stock fork tubes with 43mm tubes, and machined the triple-clamps and lower legs to fit. His team also made the disc-brake centers and rotors, and tucked the fender closer to the tire, removing all visible hardware and rivets in the process. And anywhere hardware is visible, it’s racing-style 12-point stainless. “We did that because we’ve used 12-point stuff forever in the racing world.”

Alien. With its abundance of curvy tubes, elliptical shapes, black-as-night finish and sinister profile, Canepa’s Buell Lightning resembles the creature in the movie of that name.

Ron Perry and Jeff Allen

The Sturgis’ transmission cases are treated with Kefos coating, a process used extensively in Formula One racing. It’s a lot like powder coating, but it only coats to a depth of .005-inch; so, it doesn’t fill in surface detail the way powder coating does. It also will take a lot more heat, and it doesn’t need to be scraped off of gasket surfaces.

Inside the 80-inch engine, fairly typical hop-up techniques boost power to a claimed 91 horses at the rear wheel. Actually, there are few engine modifications other than pistons specially made by Wiseco, reshaped, ported and polished combustion chambers, and a very carefully lightened and balanced crank assembly. And, of course, the carbon-fiber pushrod tubes, which most people only notice on a second look.

Detailing on all of Canepa’s machines is astounding. Take the Sturgis fuel tank, for example: The front tank mounts are gone and the tank now slides into rubber mounts on the frame. An electronic speedometer replaces the stock cable-driven item, saving space in the console, which is lowered an inch and faired into the front of the tank. And all electrical wiring runs through a tube welded into the tank. The fuel crossover tube between tanks has been relocated and hidden. The gas petcock is recessed into the tank, invisible from above. Also invisible is the left-side dummy fuel cap: Its mounting hole was filled and filed smooth before the tank received its coat of deep black gloss. And the logo on the tank is an enlarged replica of factory script, hand-painted. At a conservative guess, all that represents a couple of hundred hours of tedious work, all on things you’d never see five yards away. Subtle.

Canepa’s Harley-Davidson Heritage Springer

Ron Perry and Jeff Allen

When Canepa built his Fat Boy, he decided to be less subtle; he wanted to make people notice this bike. But while there’s more chrome and some aftermarket parts, the detailing remains. The whole frame has been cleaned up everywhere; even the plug wires are exposed only where absolutely necessary.

Canepa’s fleet also includes a sportbike, a 1995 Buell S1 Lightning. “When I first saw one of these,” he says, “I realized it needed to be finished.” Because the stock brake components came from different suppliers, for example, the PM front caliper was silver, the rear Brembo gold. Both were stripped and Kefos-coated, and the disc rotors zinc-plated to the same silver finish. New rotor-mounting plates were machined and styled by Canepa to resemble the spokes of the wheels. The many carbon-fiber parts all are Canepa originals. “Our carbon parts are lighter and stronger than the original pieces. We made aluminum molds for all the carbon-fiber pieces, so these are parts that we can reproduce and sell,” he says.

On the classic side, Canepa liked the look of his Heritage Springer, but didn’t care for the candy paint or the whitewall tires. Or the overabundance of chrome, either. “I wanted to make a more exact replica of a vintage motorcycle, so that people couldn’t be sure what year it is. And that’s exactly what has happened everywhere we’ve had it. People are sure that it’s a ’50s bike that I’ve updated with disc brakes.”

Canepa took the stock Heritage Springer’s retro look one step farther by losing the chromed rims and whitewall tires, then bolting on Panhead-style rocker covers and a simple, round air-cleaner cover.

Ron Perry and Jeff Allen

If your eyes aren’t already glazed-over from too much close-up scrutiny, check out the rear license-plate brackets on Canepa’s bikes. These usually are an afterthought, but there’s no chance of that here. Start with the Sturgis’ plate, which has no visible means of support; the plate itself was smoothed out and its protruding lip removed before it was glued to the backplate. Then some nifty little plugs were pushed into the fastener holes to clean up what is usually an unattractive area. The Buell uses a license-plate bracket crafted of carbon fiber, and the Heritage Softail’s plate is studded with good, old-fashioned bolts and nuts.

What’s next from Canepa? “I’m going to build a full custom. And it will really be off the wall. Aero strut forks, brakes mounted to the wheel rims—that kind of bike. It’ll either have the brand-new Harley motor, or a brand-new Indian engine. I’ve done designs for a new Indian motorcycle, and if that bike reaches fruition it will be awesome. What would we be building today if Indian had never gone out of business? If you could start with a clean sheet of paper and design everything to today’s higher standards, you’d end up with one truly fabulous machine.”

Frankly, we’ve been conditioned not to hold our collective breath waiting for the return of Indian; too many people over the past decade have claimed to be producing a reborn Indian, and all of them have proven to be more scam artist than anything else. But if that famous marque ever does return in Santa Cruz Style, we’re confident that it will be absolutely drop-dead stunning.