A Look At JIMS Machining And Its Early Relationship With The Motorcycle Company

This article was originally published in the 2001 issue of Cycle World’s Power & Performance.

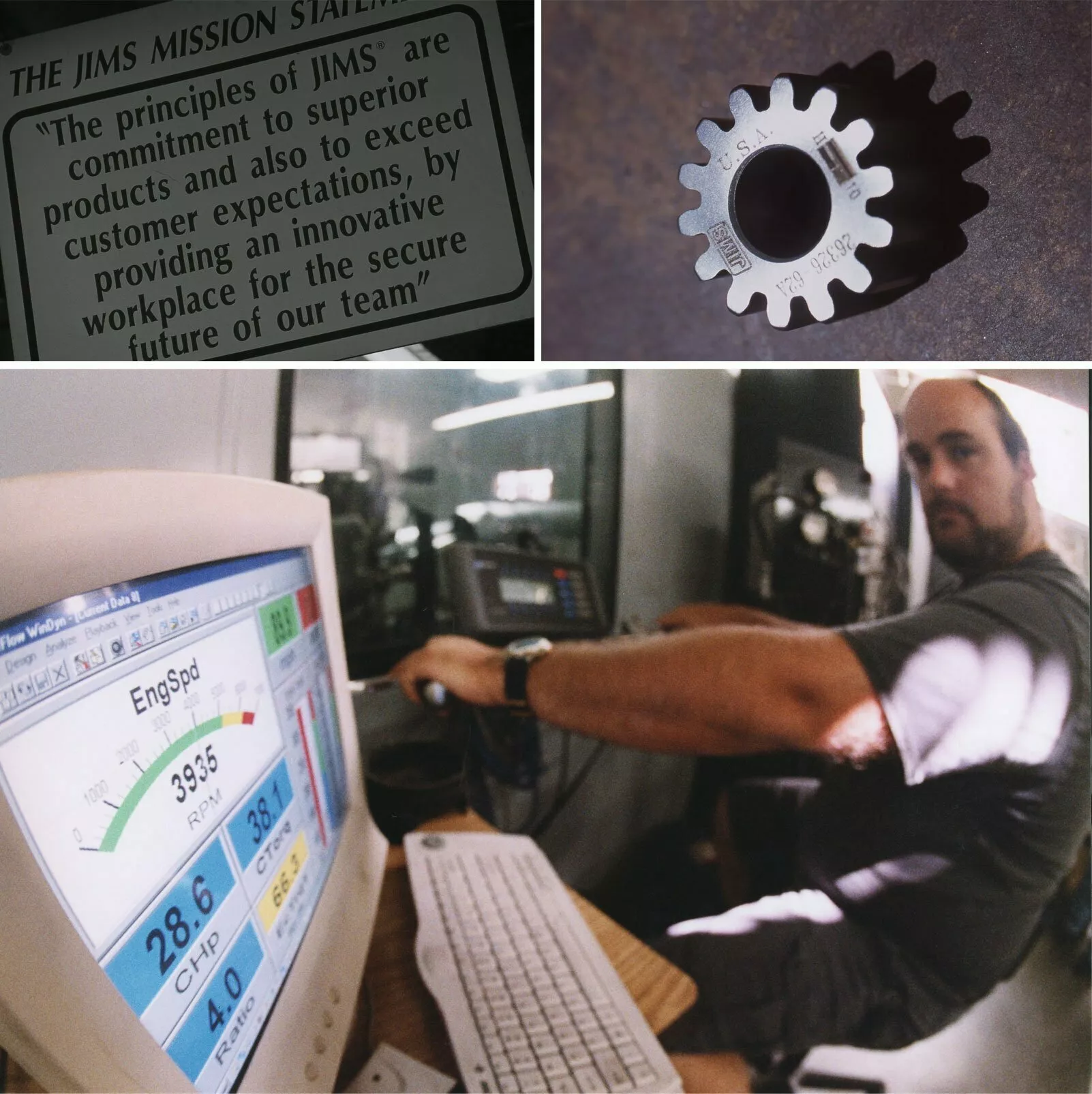

Jim Thiessen is walking around with an unusually big smile on his face these days, it’s for good reason. The company he started some 33 years ago, JIMS Machining, has just received motorcycling’s equivalent of the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval, and understandably, he’s damned proud of it.

Harley-Davidson, you see, through its line of Screamin’ Eagle high-performance accessories, has made one of the boldest moves in its 99-year history by offering the public a 103-inch stroker crankshaft for its non-counterbalanced Twin Cam 88 engines. And where does H-D get those cranks? Not from some Midwestern manufacturing giant that supplies crankshafts for half of Detroit’s who make Meat automobile production. Not from one of the high-profile car-racing operations around the country—or around the world, for that matter—that build crankshafts for all kinds of competition four-wheelers. No sir, Harley gets its stroker cranks exclusively from JIMS. And if you had any idea of how fussy The Motor Company can be when it comes to sourcing high-performance parts—especially if those parts constitute the very heart of the engine—you would understand that this arrangement is not just a feather in Thiessen’s cap; it’s the equivalent of an entire Indian headdress.

It’s fitting that the shirt Jim Thiessen slipped on over his usual daily fare—a T-shirt—just moments before this photo was taken has a blue collar: He posed for our camera willingly but somewhat uneasily, for there was real work to be done—machinery to inspect, production to check, shipments to receive.

Keith May

JIMS has come a long way since its beginnings back in 1968. “The company started out as a job shop that did machine work for the aerospace industry” says Paul Platts, JIMS’ Marketing Manager. “Jim has always been a rider as well as a machinist, and as a sideline, he would make a few odds and ends for Harleys—crankpins, some simple tools and items like that. But he got tired of the constant ups-and-downs of the aerospace business and decided to do nothing but manufacture equipment for Harleys.” That was 10 years ago, and the company has been on a nearly vertical growth curve ever since.

It didn’t take long for JIMS to become recognized as the source for all manner of H-D special tools—some that performed the same jobs as the factory tools, some that the factory never even imagined. The line of aftermarket products grew steadily, as well, not with chrome geegaws and billet dress-up pieces, but with hard parts intended to make a Harley run better, faster, longer.

Today, the company has grown to a 133-employee operation that just recently published a 228-page catalog containing more than 1000 separate part numbers. And it still is the largest supplier of H-D special tools, the listings for which take up more than 60 pages of that catalog. JIMS is not a retail operation, relying instead upon its vast network of dealers and distributors all around the world to get its products into the hands of the public. “If a customer doesn’t know where to buy our products in his area,” say Platts, “he can call us here (805/482-6913) and we’ll be glad to hook him up with the closest dealer.”

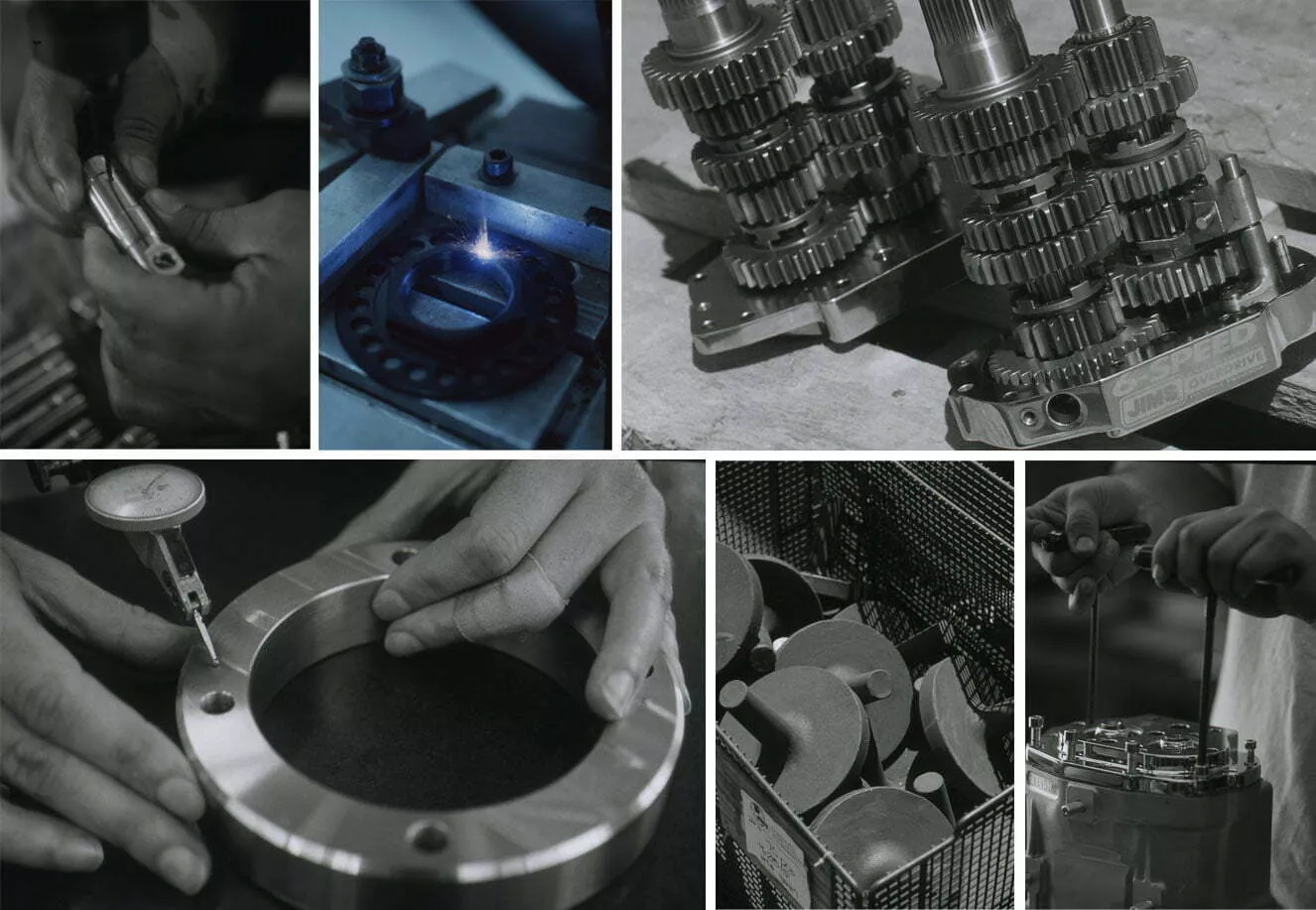

The company’s signature six-speed transmissions (on right, above) use a design licensed from Baker Drivetrain, but all the components are manufactured by JIMS. Laser-etching station autographs every part the company makes with a part number, a date code and a JIMS logo.

Keith May

JIMS is now involved in a wide area of H-D performance, with products covering most engine systems—cylinders, pistons, flywheels, connecting rods, cams, lifters, pushrods, valves, valve guides, rocker boxes, cam covers, oil pumps, you name it. One of JIMS’ specialties is transmissions, with the company manufacturing everything from the smallest transmission component to complete four-, five and six-speed gearbox assemblies. Transmissions, lifters and rockers currently are the highest-volume items the company makes, but tools still represent about 11 percent of the business.

And, of course, JIMS also manufactures stroker crank-shafts. The company has been making Evo and Shovelhead strokers for quite a few years, and just added the Twin Cam Alpha-motor strokers for the 2001 season.

Which is where Harley-Davidson comes into the picture. Actually, JIMS already had been doing business with Harley, supplying some valvetrain components to the The Motor Company’s Parts & Accessories Division. But landing the contract to build 103-inch stroker cranks for Harley was a genuine coup for this comparatively small, privately owned company. “We’re really excited to have gotten this business from Harley,” says Thiessen. “It means a lot to us and our reputation for quality. But it wasn’t easy. We had to conduct the same durability tests that Harley requires for all of its Parts & Accessories products. They’re tough tests, but we passed with flying colors.”

Originally, JIMS planned to manufacture not only the 103-inch Screamin’ Eagle cranks, but also its own strokers in 106-, 109-, 113- and 116-inch variants. The company will likely drop the 106 and 109 from the line, though, so as not to compete directly with Harley and cause confusion in the marketplace. “The Harley 103 and our 106 and 109 crankshafts all are drop-in deals,” says Platts, “but our two bigger strokers, the 113 and 116, require some machining of the cases and are intended for really serious power output. We think creating that distinction, between a simple installation and the need to make some heavy-duty modifications with a bigger motor, will help give the Harley crank an identity that’s separate from ours.”

That’s a very sensible, practical approach to a potential conflict. But then, Thiessen is, by all appearances, a very sensible, practical individual, a fact that is readily apparent as you walk through his facilities. This is no ego-driven business, no vanity enterprise with plush offices flaunting elaborate furnishings and lavish accouterments. This clearly is the operation of a hands-on, roll-up-your-sleeves owner who eschews such self-indulgences. It is the brainchild of a machinist, pure and simple. The “executive offices” are a hodgepodge of tiny workspaces crammed into just one of several long, narrow buildings in a 30-year-old industrial complex in sleepy Camarillo, Calif. You have to duck to enter some of the areas, and getting from certain offices to some of the others forces a trip through narrow hallways and around protruding desks, like a lab rat navigating a maze.

Parts for go, not for show.

Keith May

“Jim is very pragmatic about that kind of stuff,” says Plats. “When you start talking about things like new carpeting and office furniture, he thinks of that money in terms of new or upgraded equipment that can help us make better products more efficiently. He might be a successful businessman, but he’s still a machinist through and through.”

Evidence of that philosophy can be seen throughout the facility—well, as long as you avoid the offices, at least. One of the latest additions is a huge, $600,000 Nigata CNC machining cell, an elaborate, fully automated piece of high-tech equipment that performs just about every operation required to transform a chunk of forged steel into a gleaming flywheel. Like a sentinel, the towering cell stands watch over the crankshaft finishing area of the shop, its complex inner workings a one-of-a-kind marvel of manufacturing designed and built by Thiessen and his R&D department. “There’s our new carpet,” says Platts, a wry smile on his face, “but we can’t allow you to take any pictures of what’s inside the cell. That’s one of the secrets we’ve developed that has made the crankshaft program a feasible venture for us.”

Another fairly recent expenditure was the CAD (Computer Aided Design) station in the R&D department. The design team uses it to come up with everything from new products to the complete tooling schemes needed to manufacture them. Also new is a high-end Superflow dynamometer that allows the R&D people to get a more precise handle on important aspects of new-product design such as overall performance, structural integrity and long-term durability.

Every part the company makes, no matter how big or small, goes through a small office where it is laser-etched with a JIMS logo, a part number and a date code. “That can create a bottleneck,” says Platts, “but when we have a part that fails or has some kind of unusual problem, we can track it to a specific batch made on one particular day. That lets us determine if we have a whole batch of parts with a similar problem or if it is limited to just that one part. So, if you ever see a part that doesn’t have a JIMS logo on it, we didn’t make it.”

That’s not ego talking, that’s pride. And confidence in the quality of the parts the company manufactures. During the few hours we spent at JIMS, the closest thing to a display of ego we experienced by anyone was Platts’ earnest, humble request to get the name right: “It’s JIMS,”‘ he said, “with no apostrophe between the M and the 5, and the name spelled all in capital letters.”

So be it.