Motorcycle Engine Rebuilding – Branch O’ Keefe

When it comes to making power, the sky’s the limit regarding the different avenues that can get you there. In addition to turbochargers and blowers, you can go the big-inch route by putting a set of big barrels and pistons on top of your cases. This works well, but another good choice is simply to make what you have as efficient as possible. When you think about it, a Harley motor is nothing more than an air pump, pulling air in through the carburetor, past the valves, and out through the exhaust. By taking the stock components and modifying them to move more air and burn the fuel charge more efficiently, you can come up with large amounts of power not previously realized.

In an effort to prove this theory, we went to one of the oldest names in the aftermarket Harley industry, Branch-O’Keefe. If the name sounds familiar, it should. The company was started way back in 1969 by Jerry Branch and his older brother Lem-the pair went about changing people’s minds about pairing performance and Harley-Davidsons. Back then, people were getting impressive numbers out of Harley’s V-Twin, but most of that was seen on the racetrack, not on the street. That was about to change. Jerry had an extensive background working on Harleys and did everything from working as a service technician at Barfield Harley-Davidson in Memphis, TN, (Jerry tells us he even taught Elvis how to ride his first Harley!) to building heads for the XR750 race bikes and XR1000 street bikes. When the Motor Company needed some outside expertise prior to launching the Evolution motor, Jerry got the call. In addition, he was involved in some of the very first prototypes of the V-Rod back in the early ’90s.

Over the years Branch Flowmetrics (as it became known) did business in various locations in the Long Beach, CA, area. After 30-plus years of running the business, Jerry decided it was time to cash in his chips, so he sold the business to Mikuni and retired.

Jerry knew the company was in good hands, due to his protege John O’Keefe staying on once Mikuni took over. John had worked with Jerry since 1975, and he was like a sponge, absorbing everything Jerry had to offer. Over the years there wasn’t a single operation in the shop with which John wasn’t familiar. It made no difference whether it was performing R&D; on the flow bench, machining heads, or sweeping the floor-John did it all.

As it turned out, John ended up working out a deal with Mikuni last year, and he now owns the company known as Branch-O’Keefe. Here’s the kicker: Jerry (all 82 years young of him) has told John he misses the business so much, he’ll do whatever he can to help out. And help out he does-on a recent visit there, we saw Jerry on his hands and knees, building the company’s new flow bench. Now, there’s nothing wrong with the benches put out by the likes of Superflow, but, as with most other stuff, Jerry likes to do things himself. In addition to having Jerry around on a semi-regular basis, another feather in Branch-O’Keefe’s hat is the fact that the building the company just moved into has a common door with Bennett’s Performance’s new shop. The combination of the two separate companies with the ability to collaborate on projects with one another is great for both of them, but, more importantly, it’s great for us as riders. We expect to see some really great products coming from Branch-O’Keefe in the near future.

We were interested in finding out just what happens to a set of heads sent to Branch-O’Keefe for modifications. So we ran over and watched from start to finish as John and the boys worked their magic on a set of stock Harley heads that were designed to be part of Branch-O’Keefe’s new 95-inch Performance Touring package. The package is designed to give heavy touring bikes gobs of low-end torque that comes on really strong at about 2,700 rpm and stays strong ’til 4,600 rpm before tailing off. The beauty of this modification is that it uses a set of gear-drive .560-lift cams and a set of flat-top pistons running between 9.5-9.8:1 compression, allowing the engine to run on pretty much any pump gas in the country without pinging. Cost of the kit will be just shy of $2,000.

As soon as a customer’s heads show up, they get disassembled. Here, John removes the stock valve and spring.

After complete disassembly and glass-bead blasting, the key to Branch-O’Keefe’s operation takes place in the porting room. The staff uses a rotary file to widen the port, being careful not to take too much material off the floor.

The area around the valve guide gets some major reshaping to help increase airflow into the combustion chamber.

Once the new shape has been established, sanding drums of various grits are used to get the final shape and surface finish.

Branch-O’Keefe utilizes AV&V; valve guides because of the bronze manganese material from which they’re made. This alloy aids in lubrication, heat transfer, tight tolerances, and long life.

John uses a special installation tool to be sure the guide is straight in the head and set to the proper depth.

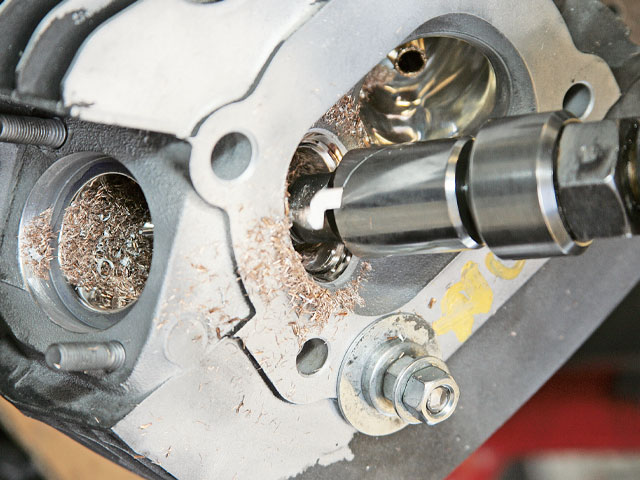

Prior to polishing the combustion chamber, the valve seats will be cut to the proper angles. The cutting tool is set up to machine 60-degree, 45-degree, and 30-degree angles, all designed to correspond to different portions of the valve.

John machined the seat on a milling machine, leaving it approximately .010-inch taller than its final dimension. This will be ground to spec later.

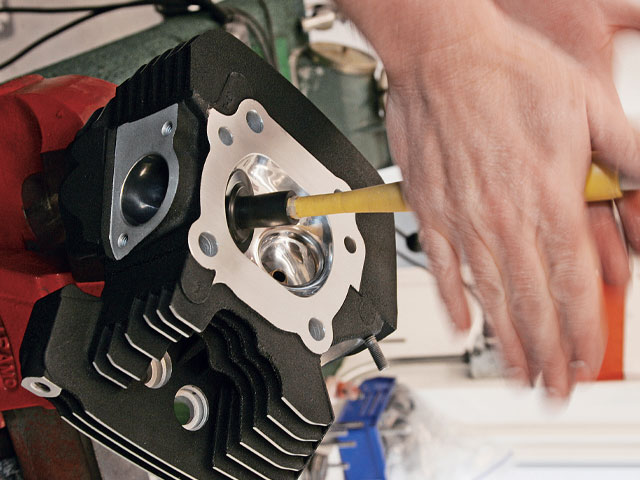

With an extra valve in place to protect the valve seat, polishing of the combustion chamber takes place. Next, the heads get a thorough cleaning and paint (if needed).

Here’s a look at a head after porting on the left, and a stock head on the right. Note how much larger the port is, and how much less material there is to impede the flow of the air/fuel mixture on the finished head.

Here’s a good look at a stock head on the left, and the Branch-O’Keefe head on the right. From this angle you can see how much more the ports are opened up, as well as the mirror-like finish on the surface.

Prior to assembling the heads, the seats must be ground to the final dimension. This grinding wheel slips over the shaft seen here and is spun by an electric valve-seat grinder from Kwik-Way until the proper height is achieved.

With a dab of lapping compound, John lapped the valve to the seat, ensuring a superior fit and seal.

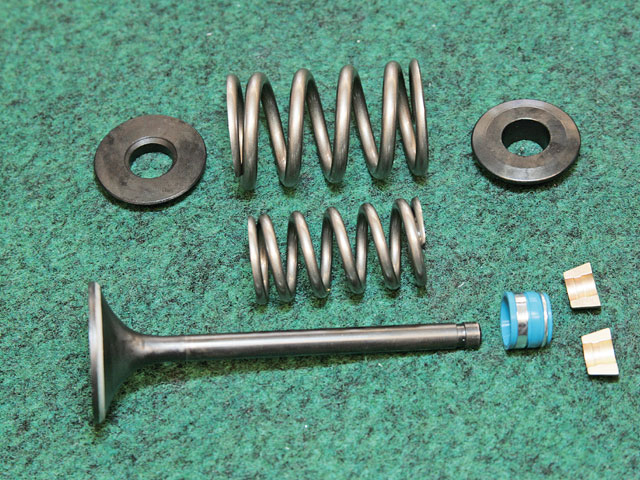

For this application, the exhaust valves measure 1.610 inches and the intake 1.900 inches. The black nitrite-coated, stainless-steel valve has a Stelite tip for excellent wear characteristics. Branch-O’Keefe also utilizes AV&V; valvesprings, retainers, shims, and 10-degree locks. Also seen here are the Viton oil seals.

A new oil seal is slipped into place…

…prior to the valve being installed.

Next, with the chrome-moly retainer in place, the valvesprings are compressed, and the titanium locks are placed in the proper location before the spring compressor is removed. The same procedure is followed for the other valve, prior to repeating the process on the other head.