Three decades of Softail

The OG ’84 FXST rolled out with a newfangled 80ci Evolution motor.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

In ’88, Harley brought back the springer fork on the FXSTS Springer Softail.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

Introduced in 1990, the beefy Fat Boy has a distinct meaty headlight nacelle, solid wheels, and floorboards. It’s also one of the most popular Softails ever made.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

The 1940s-style leather saddlebags with quick-detach buckles, full FL front fender, and chrome laced wheels and hub cover all pay homage to the past in the Heritage Classic.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

In 1999, Harley gave riders the lean and mean FXSTD Softail Deuce, with its long, slender tank and sleek front end.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

You could call the FXSTB Night Train the goth kid of the Softail family. It featured a blacked-out powertrain and wrinkle-black trim on the engine covers, air cleaner, oil tank, rear fender supports, drive belt sprocket, and fuel tank console.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

Meant to be a stripped-and-chopped bobber, the dark Cross Bones had a sprung seat, Springer front end, and half-moon floorboards.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

If the Cross Bones was no-frills, the CVO Softail Deluxe is the bells and whistles. Like Harley’s other CVO bikes, it runs a Screamin’ Eagle motor and distinct, high-end factory paint. Convertible components make it quick and easy to transform from a touring machine to a boulevard cruiser.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

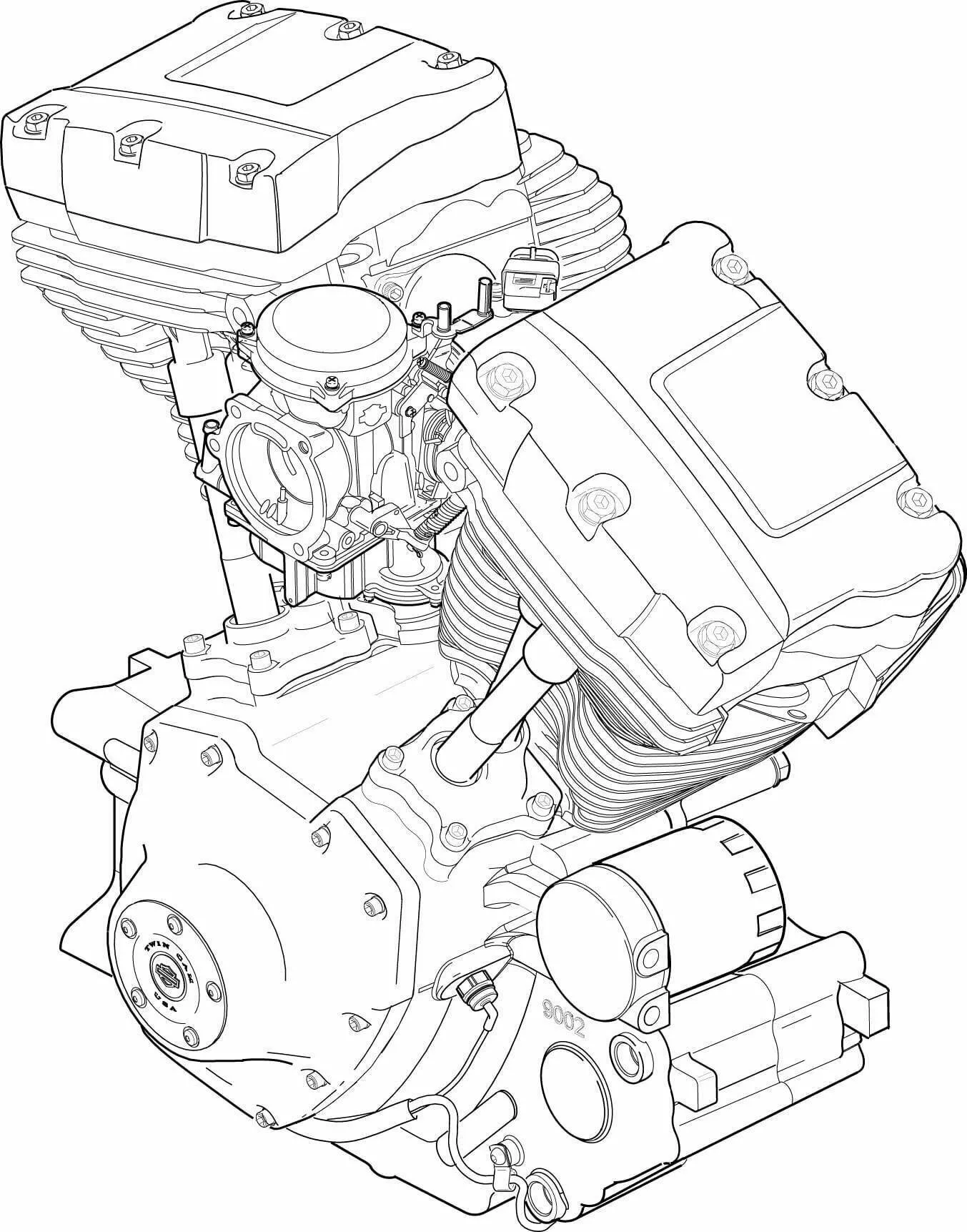

Softails have solid motor mounts instead of the rubber-mounted engines used in Harley’s Touring and Dyna lines. That means more vibration. When Harley switched over to the Twin Cam V-twin, it compensated for the extra vibration by using a counterbalanced version of the motor instead of the usual big twin in the other two model lines.

Words: Mark Masker Photography: Courtesy of Harley-Davidson

You know you’re getting old when you find yourself writing a history story about something that occurred during your lifetime. Thirty years back, when I was a high school freshman cultivating a mullet and a sparse “mustache,” Harley-Davidson launched one of its most iconic post-buyback motorcycles: the Softail. Here’s a highlight reel from the Softail’s life.

In the Beginning, There Was Biker…

Harley’s Softail might have been born in a factory in ’84, but, like some strippers I’ve known, it was conceived in a biker’s garage in the early ’70s. A mechanical engineer and avid rider named Bill Davis invented the prequel to the Softail in his garage in Missouri. He loved the look of a hardtail rigid but hated the constant pounding on his body that rigids are known for on long-distance trips. He wasn’t alone. Several people offered hardtail-style frames with plunger suspensions, but that wasn’t good enough for Bill. Only the rear axle had a spring, he found them to be inefficient, and they lacked the look of a true rigid. Davis thought he could do better and set about to prove it. Experiments started on his ’72 Super Glide in 1974.

Working in his garage, he came up with the triangular swingarm-pivot arrangement that marks all Harley Softails from that time to the present. Conceptually, Davis’ design drew from the old Vincent Black Shadows of the ’40s. The biggest difference being the twin springs and snowmobile shock hidden under the seat (the chassis hid the pivot). You could even make the argument that this idea inspired all the other hidden tech ideas customizers embraced later on down the line (yes, internal throttle, I’m looking at you). Davis instituted two other big changes that carried over to the first official H-D Softies: an oil tank reminiscent of the old Knuckle can and bending the frame rails to align with the swingarm to better sell the look of a rigid.

A lot of handcrafting went into Bill’s guinea pig of a Softail—not just all the chassis work in his garage. The AMF decals had to go. Davis also ran 10-inch over forks with custom trees, to boot. All of the sweat equity he poured into the transformation paid off with a bike that looked the chopper part minus the chopper backache.

Riders who knew Harleys loved it enough that Bill filed US Patent 4087109 in March 1976 so he could make and sell the stealthy new frame and suspension to them. Better still, he soon figured, why not take the idea to Harley-Davidson directly and see if they wanted in? A phone call to Willie G. later, he had a meeting set up in Milwaukee to show Harley’s engineers what he’d done.

H-D’s Louie Netz greeted Davis and a buddy when they rode over, Davis on his chopperized Glide and the friend on his own bike. Harley’s engineers were impressed; Willie G. came out from his office to meet with Davis and check out the bike. Not enough to commit on the spot, though. Harley’s engineering queue was chock-full of projects at the time. The Softail would have to wait.

Davis headed back to Missouri. He didn’t stay idle, though. Figuring he could make the frames himself, Davis created the jigs and other fixtures needed to make new chassis kits on his own. When he wasn’t making the 10 or so Softail frames he sold to local customers, he was either working on other bikes to pay the bills or refining the Softail’s design. By switching over to twin shocks instead of the original snowmobile setup, Davis finally lowered the seat height closer to where he wanted it. He even conjured up a Sportster version of his frame!

Worx for Me

In the middle of all this, a guy walked into Bill’s shop for some work on a Knucklehead. Davis never divulges the guy’s name. It’s not even all that important anymore. What is important is the role he played at this point. This Mr. X had the business brain to Davis’ engineering intellect. Together they launched Road Worx—the first Softail manufacturing business to sell that frame as we know it. Mr. X conducted marketing surveys, secured capital, and got the ball rolling. Harley hadn’t lost interest in the Softail, though. Harley’s VP of engineering, Jeff Bleustein, championed the frame, and H-D made Davis an offer for it, but the offer was a little light for his liking.

Bill went back to work, looking for ways to make the frame better. There was a never-ending battle between the seat height and the shocks. Set the seat too low, and the springs scraped its pan. Set it higher, and he’d lose the chopper lines he wanted. Desperation triggered inspiration—precisely, relocating the shocks to under the tranny. Solve one problem, though, and usually create new ones. Just like this idea did.

The space under the transmission isn’t exactly roomy; normal-sized shocks would bottom out on pavement. There was also the minor matter of shock design. Bill needed a shock that worked on tension; all the other ones he knew of relied on compression. Polyurethane being self-damping, he solved both problems with a compact new shock cylinder made of the stuff. After vigorous road testing, his new “Sub Shock” Softail was ready for the run to Sturgis.

At least, that’s what Bill thought. When he and Mr. X hit the road, they knew the Sub Shock could take a pounding. What they didn’t know, and found out in a bad way, was that heat buildup broke down the polyurethane over time until it rode more and more like an actual rigid instead. Bill’s anonymous business partner eventually rode the latest Softail home while Davis continued on to Deadwood. Misfortune struck there, too. Some jackass paid him the courtesy of robbing his saddlebags while Davis was in town. That was enough. He got on the bike, headed home, and got back to the drawing board. Back to metal springs and oil dampers.

Super-heavy-duty industrial springs were small enough to fit in the damper housing. That took care of the space issue. Running the absorbers on tension instead of compression meant designing his own valves and pistons for the job.

At this point, Mr. X hit the ground running. Road Worx became a real business, and orders started coming in… And the shit hit the fan. Davis and his business partner butted heads bad. Real bad. Like, destroying-the-company bad. Left hanging for the business loans after the split, Davis revisited selling the design on the advice of his attorneys.

Aftermarket companies were interested in the design. They just wanted it at scandalously low prices. Davis eventually turned back to Harley-Davidson. This time Bleustein got him a much better offer: royalties, albeit with a lifetime cap. Meaning, for every unit sold Davis got a piece of the action until said cap was met. He wasn’t thrilled with the idea of the money capping out over time, but he took the deal anyway. On January 6, 1982, he sold the patents, prototype, and tooling for his Sub Shock design to The Motor Company. In June of 1983, the world at large met his vision in the form of the 1984 Harley-Davidson FXST Softail.

Risky Business

I’d bet any amount of money Harley was more eager the second time around due to the AMF buyout. When those 15 execs bought H-D back from AMF in the early ’80s, the future looked bright. And bleak. Tossing off the overlord’s yoke freed Harley to go in a new direction. That was the good news. The bad news was Harley-Davidson needed to reinvent itself if it was going to live, much less thrive, in the face of foreign iron gobbling market share. Harley needed a hero, and it needed it now.

Buying out an aftermarket design isn’t exactly SOP at most motorcycle manufacturers. Harley-Davidson isn’t exactly an exception to that, either. This was definitely a desperate time for the company, so maybe a desperate measure was justified. Looking back, those first few post-buyout years saw some pretty big changes: the Evo motor, the Evo-esque Sportster twin, the FXR, and, of course, the Softail. On the surface, buying the Sub Shock design might look like risky business; no one knew for certain how big a market there’d be for a non-hardtail hardtail. What everyone did know was that people liked the old rigid look, and Davis’ bike packaged it in a way that might just be a big seller. Moreover, he’d already done most of engineering design on it. All Harley really had to do was adapt it into what it wanted. Mostly, that meant fitting the frame to the new Evolution motor and creating the aesthetics. That’s why it only took six months for H-D to get the Softail from prototype to production.

The FXST was an instant hit that boosted sales. By 1988, Harley found an even better niche for it with the nostalgic Springer Softail.

In the three decades since Harley put the first Softails on its showroom floors, its chassis haven’t changed much. Yeah, there’ve been wide rear tire kits, air suspensions, and Harley changes the trappings on the stockers, but why mess with an icon? They’ve only gotten more nostalgic over time—mostly thanks to Davis and his early Sub Shock version more than 30 years back.