Bringing Back Memories Of A First Harley-Davidson Panhead Purchase

This article was originally published in the August/September 1998 issue of Cycle World’s Big Twin magazine.

You always remember your first Harley-Davidson—the sheer wanting of it, the way you coveted that unmistakable sound, the near agony of yearning to ride it, to caress it, to see it sitting in your garage.

Then, when you finally got it, it was fine beyond your wildest expectations; when you rode it, you were royalty. You spent untold hours cleaning and polishing it, becoming familiar with every bolt and heartbreaking little scratch until you could recognize your bike blindfolded from a hundred other Harleys.

Yep, you invested too much of yourself in the white-hot desire for that motorcycle to ever forget the first one.

That’s exactly the way it was with my first Harley, at least. It was a jewel of a ’63 Panhead I bought in 1965 when I was a senior at Sparks High School in Sparks, Nevada. Sparks is adjacent to Reno, which usually elicits a tired old joke that says Reno is so close to hell, you can see Sparks.

The owner of Reno Harley, “Mac” McDonald, told me he had a dresser that had been crashed, and that he’d repair it, repaint it and make it like new if I wanted to buy it. I enthusiastically agreed, and in October of 1965, I was the proud owner of a beautiful Harley-Davidson Panhead.

In those years, not only were there very few motorcycles in the parking lot of good old Sparks High, I was the only one who rode a Harley to school. In fairness, it must be noted that fellow student and football teammate Mel English also owned a Harley dresser, but I don’t recall ever seeing his bike parked in the lot.

I rode my beloved Pan to school every day, sun or snow, even though it was the most cantankerous, ornery, hard-starting bike I ever owned. But then, all the effort I expended to start it merely bonded us together even more. If I could have fit it in through the front door, I would have slept with that motorcycle.

Actually, the bonding started from the first day I owned the bike. After I had made the deal to buy it, Mac needed a couple of weeks to get it ready. In the meantime, a linebacker from our cross-town rivals, the hated Reno Huskys, had ground my right knee into powder, and I was scheduled for surgery the next Monday, the very day I was to take delivery of my Panhead. As I lay in the recovery room, with my parents standing next to my bed, the first words I could gather enough strength to utter after regaining consciousness were: “Is my bike done?” When they told me that it was, I couldn’t wait to see it. And when I finally got home and viewed it for the first time, it was even more beautiful than I had anticipated.

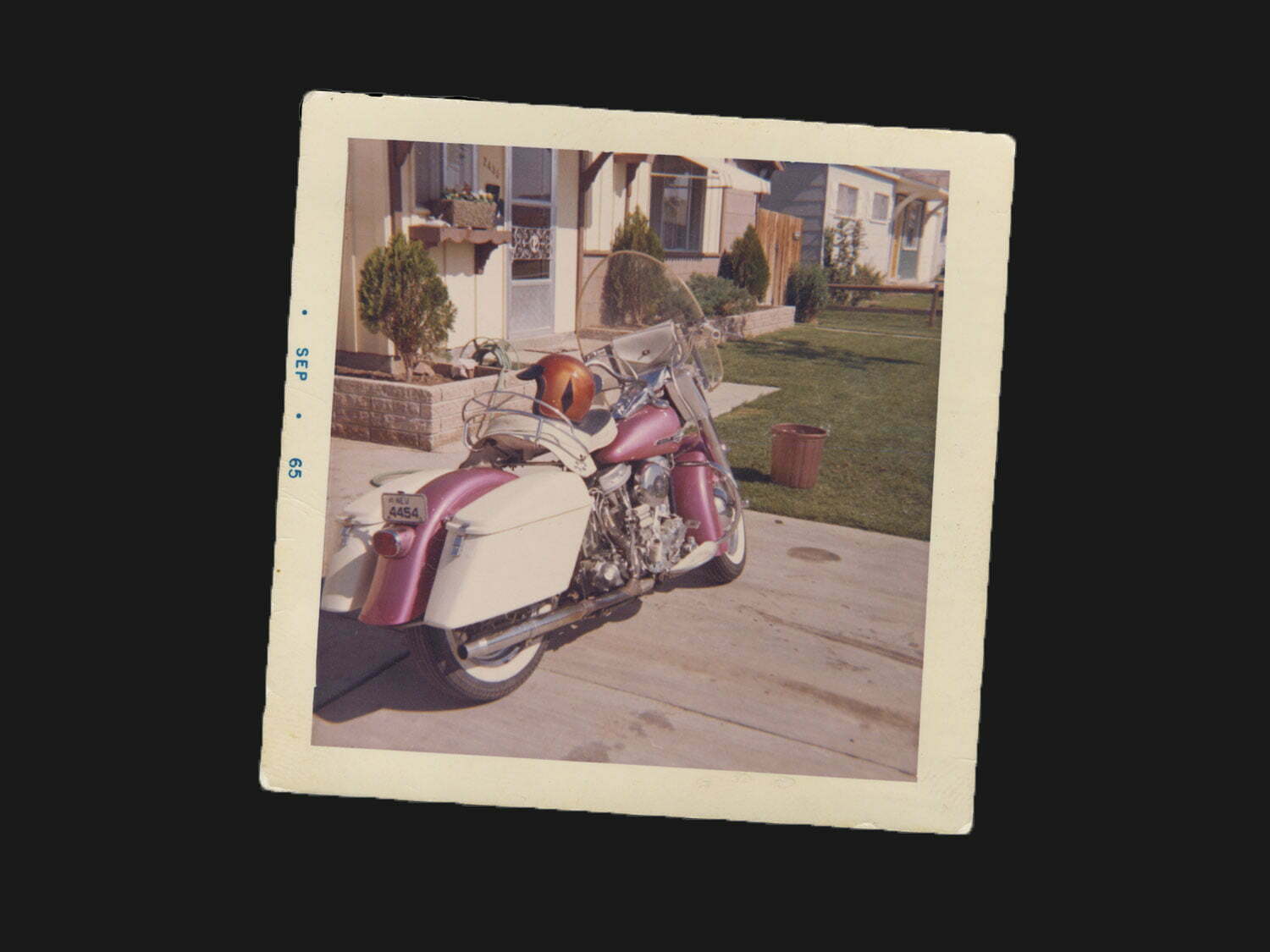

A snapshot of the author’s beloved ’63 Panhead that he purchased in 1965.

Beau Allen Pacheco

Since I wasn’t going to be throwing any more passes on the gridiron that season, I planned on riding to the annual AMA-sanctioned Death Valley run the weekend after surgery. I pleaded with the doctor to let me go, and finally he threw his hands up in disgust, saying that if I wanted to go out and ruin his handiwork—and my leg—he couldn’t stop me. Permission enough.

So, right after school the next Friday, in the face of a threatening snowstorm, my father kicked my bike to life and lifted me into the saddle. My right leg was heavily bandaged and terribly swollen, so I had to keep it immobile. Luckily, I was able to strap my crutches to my leg and use them as splints to keep the leg straight.

My Mom and Dad and I (they rode Harleys, too), along with five other bikers, rode all night through the thickening gloom on Highway 395 to Death Valley. We roared on in the Nevada desert, crossing over into California, my stitched knee throbbing to the beat of the Panhead. It is forever imprinted in my memory that as we rumbled through the town of Bridgeport, the lighted sign on the bank flashed that it was 11:15 p.m. and 25 degrees. I’ve never again been that cold. On the bright side, however, the intense cold brought the swelling in my knee way down!

Those are the kinds of adventures that make your motorcycle kin to you. The bike becomes more than a mere machine; it becomes your brother. I loved that first Harley, and over the years I’ve cursed myself mightily for selling it.

So, it was with much glee that I received a letter from Scott Meyer of Lake Tahoe (60 miles from Sparks), asking if we’d be interested in seeing the show-winning 1963 Panhead he’d bought in Georgia 20 years ago. I was blown away by the pictures of the bike and said I’d love to see it. I asked if I could ride it, and a meeting was scheduled.

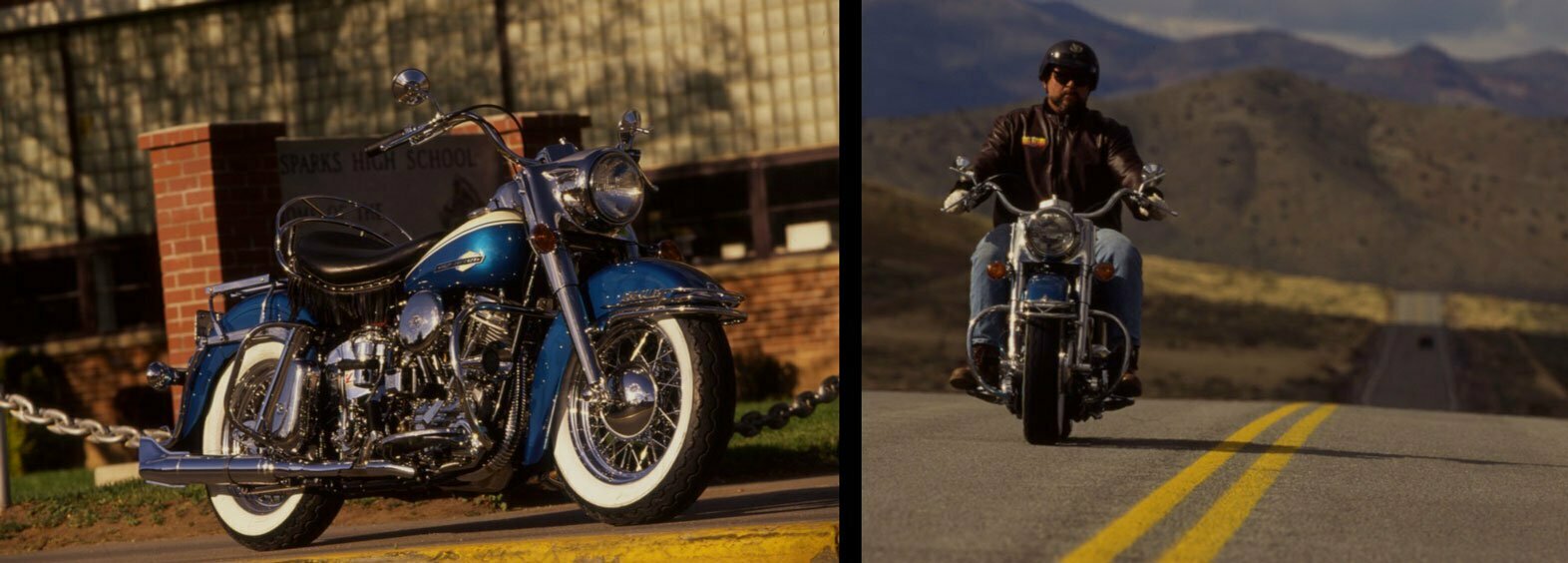

Now, if one is going to “go home again,” one ought to do it right. So, to make this reunion complete, I arranged to meet Meyer in Sparks in front my alma mater, where—in my mind, at least—I had been the king of the school when aboard my Harley-Davidson.

Meyer’s Panhead is pristine and recently has won numerous “Best Of Show” awards. When he bought the bike, it had just 1200 miles on the odometer, and since then, he has done a frame-up restoration. He rides the bike regularly, albeit for short distances; it has just 6800 original miles on it now.

Although Meyer’s bike is the same year as my old beloved, it does have a few differences, besides not wearing its windshield and bags as mine always did. My Pan was a plain FL, while Meyer’s is an FLH, which means it has five extra horsepower via higher compression and a hotter cam.

Scott Meyer’s lovely Panhead today looks just as much at home in front of the author’s alma mater (left) or cruising Nevada’s high desert (right) as it would have back in 1965.

Jeff Allen

After all these 33 long years, I wondered if the Panhead was as good as I remembered. Only riding would tell, so out on the dry, desert Pyramid Lake Road where I used to ride so often, I took ’er for a spin.

Just mounting the Pan stirred a thousand memories. First and foremost, the seat height and overall feel is far different—and better—than on its modern-day equivalent, the Road King. I never thought I’d say something like that; I’m a Road King fanatic, but the Panhead positions the rider on a far loftier perch where the legs can stretch out and keep from cramping up. Back then, the low look wasn’t in fashion, but comfort definitely was. And the pogo saddle, although a bit soft in the spring for my considerable bulk, is far superior to anything I’ve been on since.

“Want to kick it over?” asked Meyer?

“Absolutely!” I crowed and did the drill: Turn on the gas and apply the choke; switch off, stroke it through four or five times to get mixture in the cylinder; retard the spark with the left grip; turn on the switch, kick with all your might five times, then curse like hell. To my dear old Mom’s dismay, kicking a Panhead is where I learned the language that the poet Robert Frost says “rolls up its sleeves and goes to work.” Well, I went to work, all right.

On my old Panhead, I worked hard, worked until my legs ached, worked until I was out of breath, worked until even on cold nights after football practice, I was finally stripped down to my T-shirt and sweating like a pig trying to start that son-of-a…sweet old thing.

Some things never change, and Meyer’s Panhead is no different than mine: I couldn’t start his bike, either. Finally, after a couple of thousand calories worth of work, sweating and swearing, she roared into life under her master’s touch, and the sound was worth the effort. The bike sounded glorious just like I remembered.

By today’s standards, the controls feel antiquated and somehow detached from the rest of the bike. The clutch pull on the left hand in conjunction with the throttle twist of the right hand feel somehow incongruous, like maybe they’re from two different bikes. A disjointed endeavor—just like I remember.

I eased out the clutch and headed out on my old highway where the scent of damp sagebrush heightened my recall process. Rumbling down the road was sheer bliss, and again the memories cascaded: Yes, the bars were low, weren’t they, and easy to move around in their mounts; the glow from the neutral and oil lights was ethereal; leaning into a turn was steady and sure.

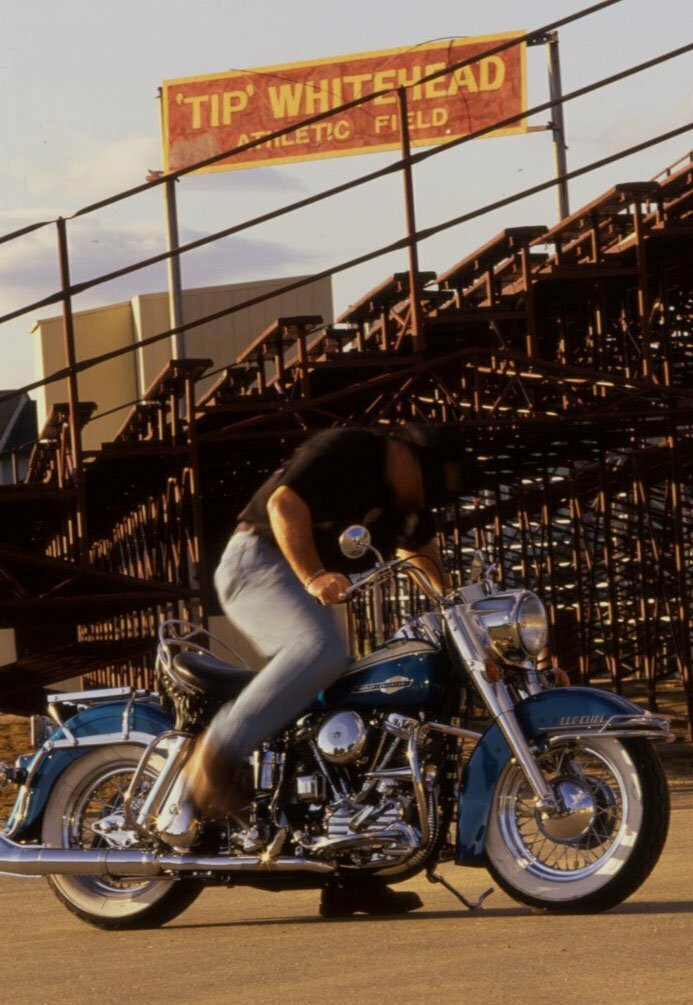

“I was amazed at the smoothness of the Panhead; either these motors are smoother than I remember, or this particular bike is exceptionally smooth.”

Jeff Allen

I was amazed at the smoothness of the Panhead; either these motors are smoother than I remember, or this particular bike is exceptionally smooth. Whatever the reason, the vibration from the Big Twin was subdued and vague—just like the brakes. Disc units have been a wonderful addition to motorcycles, and I don’t lament the passing of the old drum setup at all. Stopping the Pan took some forward planning.

But then, this is a motorcycle from an age in which you had to participate in the ride far more than necessary with modern bikes. Ad-just-ing the spark, for an example, is a lost art. As I came to a mild hill, I was reminded that this is a four-speed bike, and there are some situations at certain speeds, like this hill, that call for some skill to keep the motor happy.

I was going too fast to downshift, but slow enough to where the motor was starting to lug a bit. No problem; just retard the spark and the Panhead smoothed right out. But one had to be careful: Too much retard and the bike slows too much, not enough and the lugging gets worse. Sure, it took some time to master the technique, but that was all part of riding a Harley.

The transmission is about as clunky as a modern Harley’s, but shifting felt far different. When changing gears, I was reminded of how long the shift-lever throw was, like bringing up a bicycle pedal in full arc.

I rode Meyer’s bike for the afternoon and was overjoyed at the experience. In my youth, I rode such a bike for thousands of miles, and I would gladly do that again on this bike. And, may I say here for the record, I would gladly be 17 years old again, too!

Sure, this motorcycle is dated and slow; it is, after all, more than a quarter-century old. But that only emphasizes the fact that Harleys have improved vastly—more, even, than many critics are willing to admit.

To my eye, the Panhead is the most handsome motor ever to roll off the Milwaukee assembly lines. It looks exactly like a motorcycle engine should: more majestic than the Knucklehead that preceded it, more substantial than the Shovelhead that replaced it.

Sitting on Meyer’s Panhead in the parking lot of Sparks High, the engine clinking and spinking as it cooled off from our ride, I pondered the old question: Can you ever go home again?

Yes and no. I don’t think I’d live in Sparks again; too many changes, too many strangers. This isn’t my town anymore.

But someday, I’ll own another Panhead—although I’ll have to save some serious bucks to get a nice one. In 1965, I paid $1200 for my Pan; right now, in 1998, Scott Meyers would take no less than $25,000 for his blue baby.

But after riding this Panhead again, I can say that it would be worth the money.

Every single penny of it.