John Harmon’s Legacy

The Holland and Harman connection

Words: Mark Masker, Photos: Courtesy of Executive Choppers and the Hot Bike/Street Chopper archives

The Holland and Harman connection

Words: Mark Masker, Photos: Courtesy of Executive Choppers and the Hot Bike/Street Chopper archives

The Holland and Harman connection

Words: Mark Masker, Photos: Courtesy of Executive Choppers and the Hot Bike/Street Chopper archives

The Holland and Harman connection

Words: Mark Masker, Photos: Courtesy of Executive Choppers and the Hot Bike/Street Chopper archives

The Holland and Harman connection

Words: Mark Masker, Photos: Courtesy of Executive Choppers and the Hot Bike/Street Chopper archives

The Holland and Harman connection

Words: Mark Masker, Photos: Courtesy of Executive Choppers and the Hot Bike/Street Chopper archives

The Holland and Harman connection

Words: Mark Masker, Photos: Courtesy of Executive Choppers and the Hot Bike/Street Chopper archives

The Holland and Harman connection

Words: Mark Masker, Photos: Courtesy of Executive Choppers and the Hot Bike/Street Chopper archives

The Holland and Harman connection

Words: Mark Masker, Photos: Courtesy of Executive Choppers and the Hot Bike/Street Chopper archives

The Holland and Harman connection

Words: Mark Masker, Photos: Courtesy of Executive Choppers and the Hot Bike/Street Chopper archives

The Holland and Harman connection

Words: Mark Masker, Photos: Courtesy of Executive Choppers and the Hot Bike/Street Chopper archives

The Holland and Harman connection

Words: Mark Masker, Photos: Courtesy of Executive Choppers and the Hot Bike/Street Chopper archives

The Holland and Harman connection

Words: Mark Masker, Photos: Courtesy of Executive Choppers and the Hot Bike/Street Chopper archives

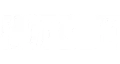

Signature moves. Every legend has at least one. Darth Vader had the force choke, Lone Ranger had his silver bullets, and John Harman had his famous internally sprung girder front ends. Unlike the others, though, Harman’s was real.

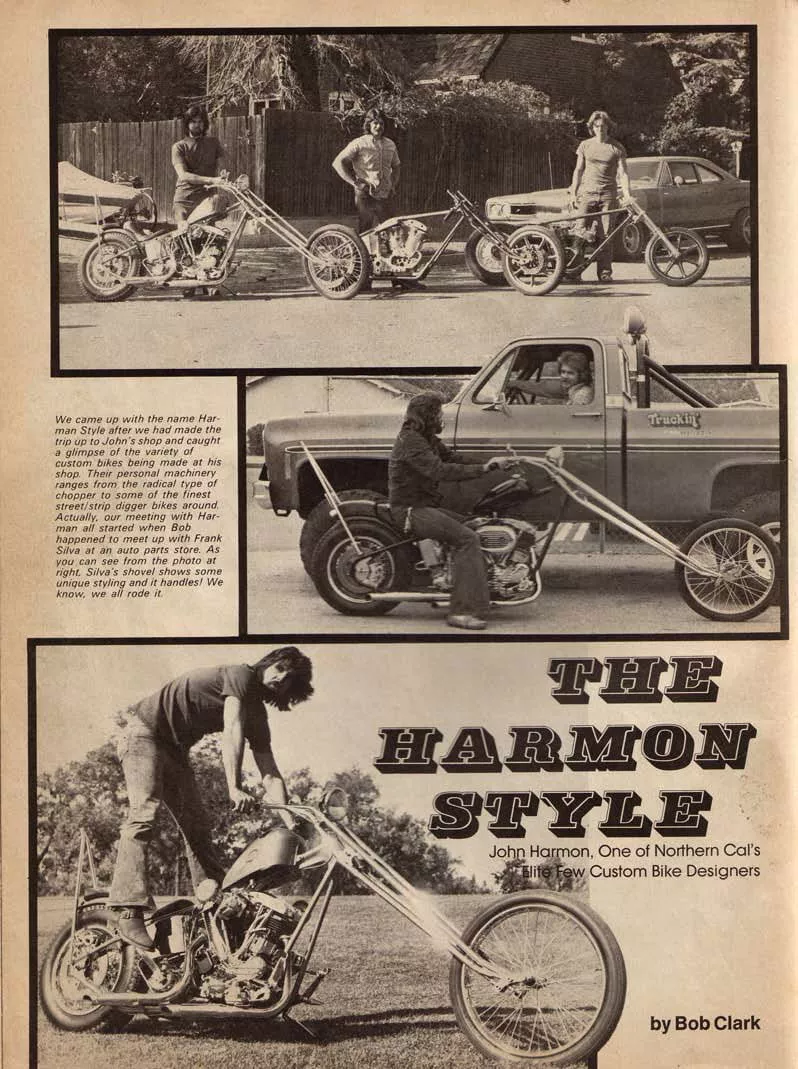

His shop, known as H&H or Grand Prix Racing back in the ’70s, wasn’t just a factory cranking out long front ends for choppers. It was much, much more than that.

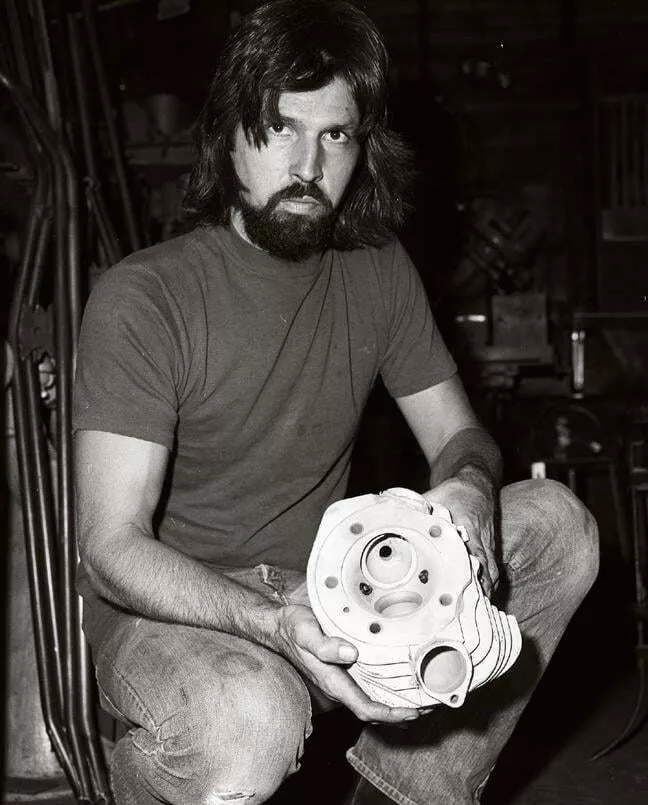

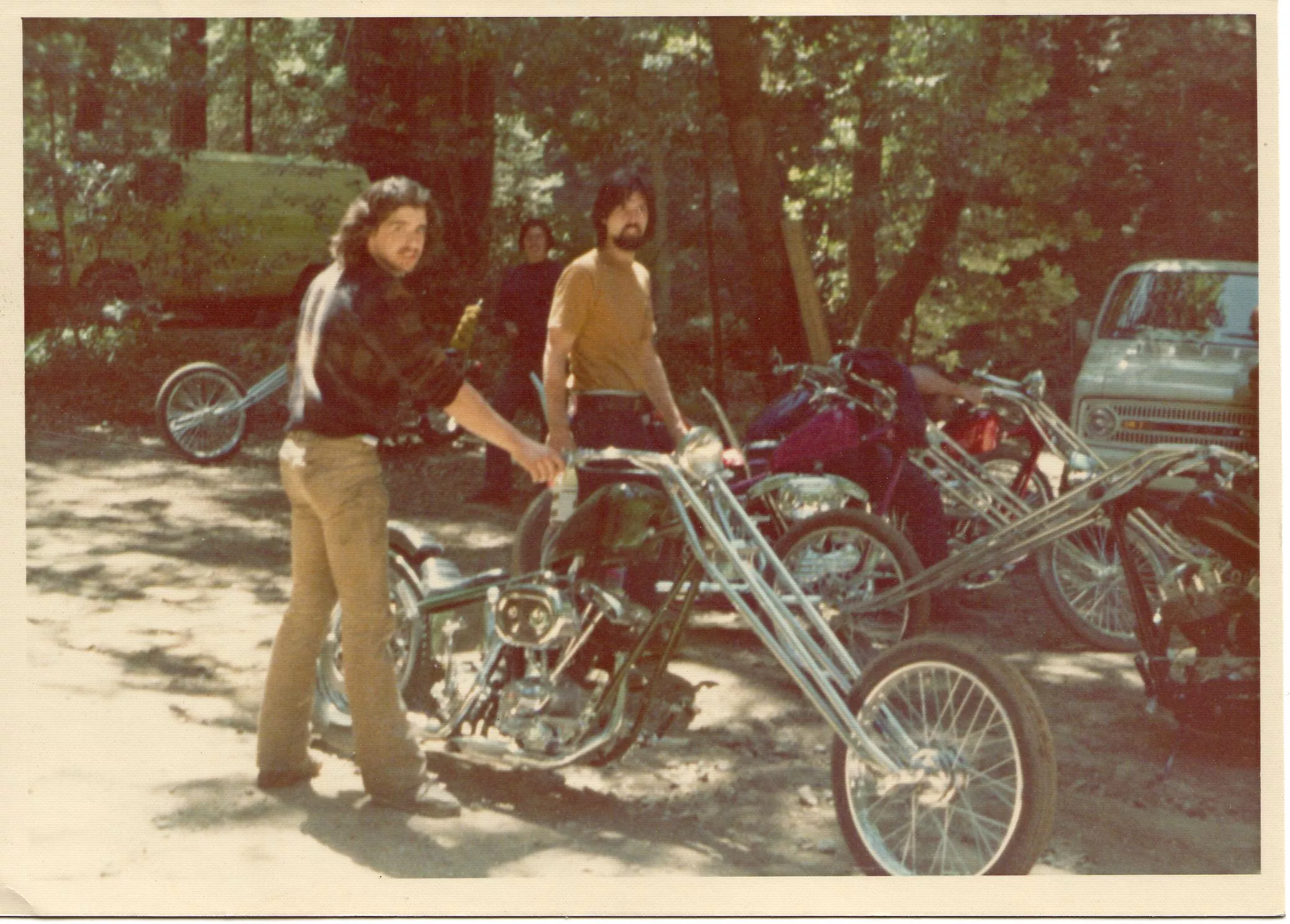

The internally sprung girder was indeed a rolling moniker for John and his two partners, Harry and Bill Holland. That’s just the tip of a much larger iceberg, though. Frames, motor work, and a lot more came out of John’s in-home garage operation, including ground-up chops in the long, popular Northern California style that made its cultural mark back then.

He was in business by 1970. Although Harman’s shop was in a home garage in Roseville, California, it wasn’t a small operation. Unlike most home garage operations of the day, Harman had everything from a heli-arc welder to a flame cutter. While John was dreaming up the next big thing, Harry Holland did the PR work while Bill fabricated the girder front ends. John also had engine work going, including heads, flywheels, and cylinders.

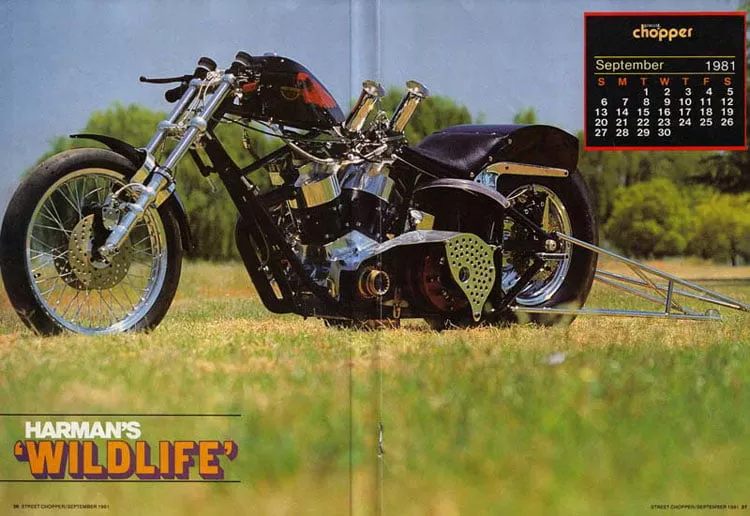

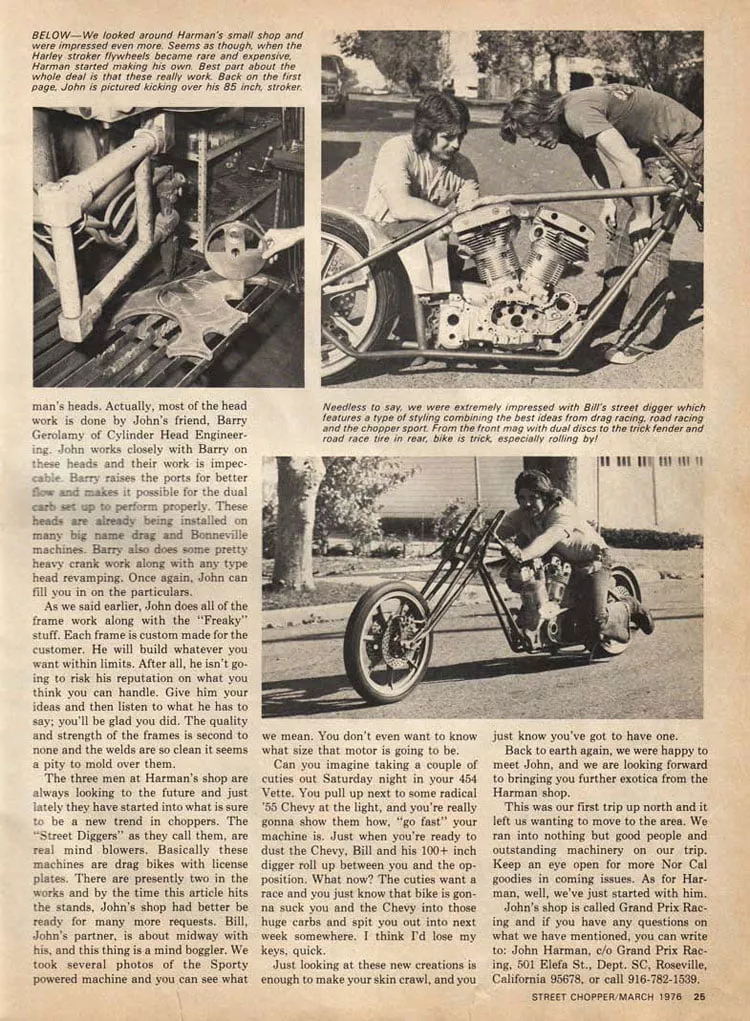

In ’76, Harman started a style they called “Street Diggers.” They were basically chopperized drag bikes. Back then the performance side of the shop was called Grand Prix racing.

John Harman is no longer with us, having passed away in the 1980s. His spirit continues on through his business partner, Bill Holland, who opened Executive Choppers in 2001. Bill now makes both the Harman girder front ends as well as full-on custom motorcycles 3 miles away from John’s original garage. We ambushed Holland long enough to pump him for a look into chopper history.

HB: What were John and your brother like?

BH: John was a very likable guy. He would help anyone who needed it. He had a great disposition of life and a great sense of humor. His talents were exceptional, especially when it came to fabrication. He could figure things out and had great problem-solving skills, and he could build just about anything he wanted. My brother, Harry, was and still is my hero. I always looked up to him not just because he’s 12 years older than I am but because he was just cool. Everything he had from hot rods to motorcycles was cool. Growing up he taught me the difference between making things clean or gaudy—like not putting too many decals on my model cars. He was a tough guy, willing to fight at the drop of a hat, but he had a soft side as well. He had more friends than anybody I ever knew.

HB: How did you guys meet John Harman?

BH: My brother was a Harley guy, and he and his buddies would go to Angels Camp every year. On the way back one time, my brother saw a guy [John] broke down on the side of the road on a Triumph. My brother stopped to help him. They became good friends, and we turned John into a Harley guy. My brother would end up spending a lot of time with John in his shop/garage, and he would take me up there to hang out and watch them work. It was very inspiring!

HB: How did all three of you go into business?

BH: John was always into fabricating, from bucket Ts to motorcycles. He used to work for a company in Lincoln called Kellisons, where he worked with fiberglass building bodies for dune buggies. My brother worked as a truck driver then went to work for Animal Control in Sacramento. I had four years of metal shop in high school. I graduated in 1970. When John and my brother decided to go into business, they both quit their jobs. I went to work for them right out of high school.

HB: Tell us about working out the details for manufacturing the front ends back in 1970.

BH: John came up with the idea of the internally sprung girder after building a prototype girder with leaf springs. He started with the leaf spring idea with one of his best friends from high school, Harry Blake. Harry went on to other work while John pursued the idea of coming up with a design that worked for long front ends. After completing the prototype and showing it off on his bike, other people were interested in them, and the sales began. Fixtures were made for semi-mass production. After building dozens of front ends, we would discover what changes could be made to improve not only production but the quality of the product. John and my brother worked on all the details of how to manage the sales and production schedules. I was the kid in the background, grinding, drilling, and doing some of the welding.

HB: How was building back then better than now?

BH: Almost everything we built came from our own hands without the use of CNC machines. We had lathes and mills, but you had to know how to use them. It was a skill that took many hours to master. We were young. John and I would have to force ourselves to go home and sleep because of our passion and drive to build something cooler or faster than anyone else had. We had fun working off of each other’s ideas, joking, and laughing.

HB: When did it close down in the ’80s? What did John do after that?

BH: At that time I was solely responsible to produce the front ends, and John was to build the frames. I built close to 4,000 units until the late ’70s, early ’80s. I got burned out from the repetitiveness. When the style of front end changed back to the shorter tube style, and the long front end market grew slower, I told John I needed to take some time off. I didn’t know how long; I just needed some time to figure it out. John, who was always into the performance end of the industry, became a major player in the big-inch V-twin platform side. After many years of producing 120- to 150-inch motors for street and strip, he came down with cancer and needed to sell the business. Kenny Boyce bought it, and he needed some front ends built, so I produced what was needed. Pretty soon the request for that front end dried up. Kenny Boyce started building some of John’s engines and started building his own style of frames for FXRs. I, in the meantime, retired the original fixtures to a storage area in my shop.

HB: How’s the new Harman/Holland front end different from the old one?

BH: The original front end was patented by the theory of its function, which was an internal compression spring in the rear leg, which worked off a rocker system. The front end also had the handlebars incorporated in the front leg and was made out of 1-inch OD by 0.065-inch wall 4130 chrome-moly tubing. The trees were 1-inch thick steel and were 4-3/4 inches wide—hardly enough room to accommodate a small drum or disc brake. Back then there weren’t front-brake laws, so spool hubs were the main choice. The forks had 6 degrees rake built into them, which made these front ends handle extremely well when set up with the correct rake in the frame. We also built the front end with no bars, where the user would run their own handlebars with the holes provided in the top tree.

In 2001 after watching how the bike-building arena seemed to be opening back up, some of my old friends were coming to see me in my iron fabrication shop to convince me to start building bikes like I used to. After some contemplating, I decided to bring the front end fixture out, dust it off, and it all came back to me about how many of these girders I made, and I thought if I’m going to get back into this, I’m making some major changes, all for the better and for safety. First change was to make the new style with billet aluminum trees 1-1/4-inch thick, the center shaft thread up from the bottom to give the top tree a clean smooth look. The front leg of the fork is 1-1/4-inch OD 4130 chrome-moly, and the rear leg stayed the same at 1-inch OD by 0.65 4130 chrome-moly. I had the original springs remanufactured so there would be another inch of travel. The rod in the rear leg that attached to the rod end on the rocker is now 316 stainless steel. The front end has adjustable rake plates in the web where the bottom tree bolts to the fork. It has six locations with the three oval rake plates, so I can adjust the rake from zero to 6 degrees in 1-1/2-degree increments. The original front end with the 6 degrees built into the web was originally designed for the long front-end trend. When I redesigned the front end, I wanted to be able to put it on stock Harleys, and with the adjustable rake along with redesigning the trees by taking 3/4 inch of the offset out and shortening the rocker where the axle goes by 1/2 inch, I’ve achieved my goal. The rockers are now keyed with the supplied axle, so the rockers stay parallel with each other. Before when you would tighten the rockers, they could twist slightly, which would make the front wheel not track correctly. With these changes and a few other minor ones, this front end is far superior to the original. But, I still build the original style for some of the old fans who had or knew of the original and want to relive their past.

HB: How was opening a shop in the ’70s different than now?

BH: Laws have changed, and there’s a responsibility to the public to build a high-quality product that is pleasant to look at, great to ride, and has a high safety rating—not that we didn’t do that back in the ’70s. After 4,000 units and, to my knowledge, not a single failure, I think we did a great job back then. Also, everything is so much more expensive now. We used to sell the front end for around $225. Back then it cost $50 to chrome it, and today it is close to $850 for the shiny stuff.

HB: How has creating choppers changed for the better now?

BH: Nowadays we have technology that makes some things easier. The materials seem to be better. When I got back into manufacturing this front end, the first thing I said was that I don’t want to get burned out on repetitious work. With the CNC lathes and mills I can have all the small parts—such as bosses, collards, triple trees, and rockers—waiting on the shelf for when they are ready to be welded and assembled. I still make the spring system, bushings, and forks by hand because I build 30 different lengths of front ends, and I can’t inventory each one of them, so they are built to order.

HB: What would you like mentioned most in this article?

BH: If it weren’t for my brother and especially John Harman, I’m not sure what type of work I would be doing today. I keep John’s name alive by still including it on the description of his front end. He was my mentor, teacher, and friend. There is not a day that goes by that I do not think about him. He died way too soon. HB

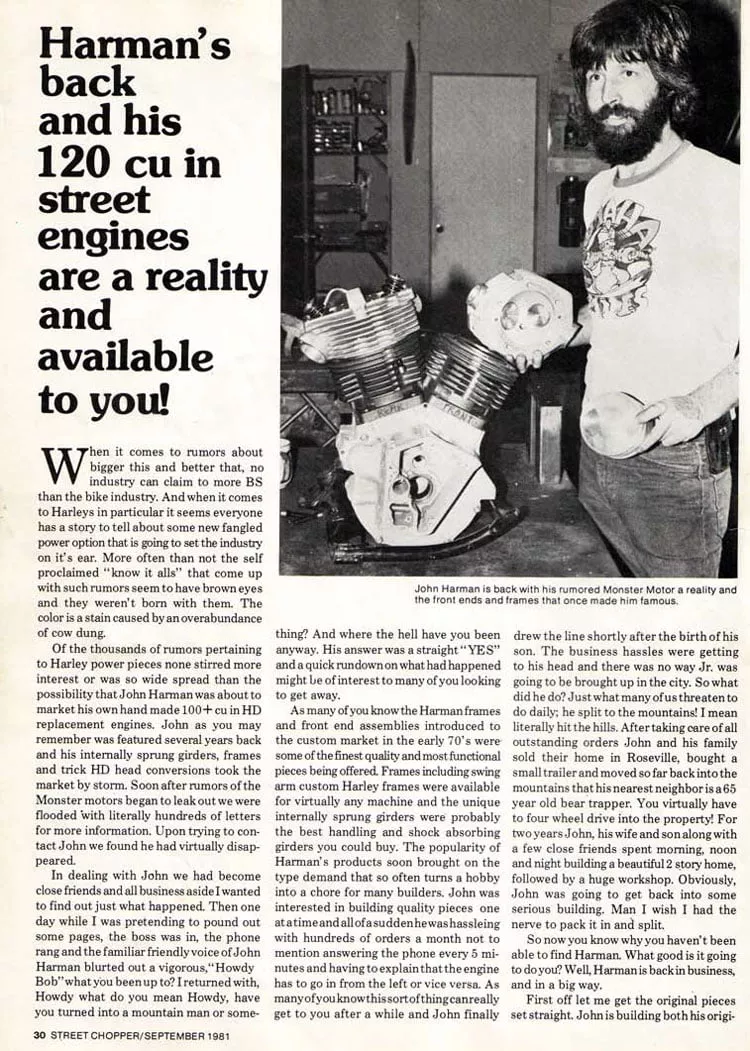

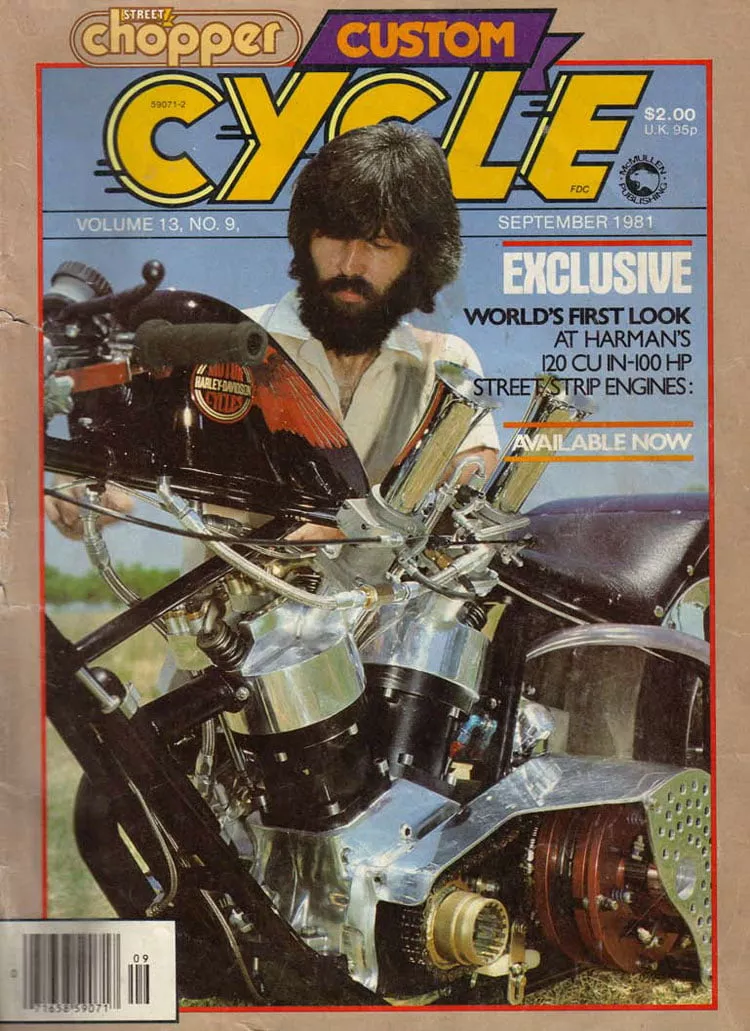

Harman Motors?

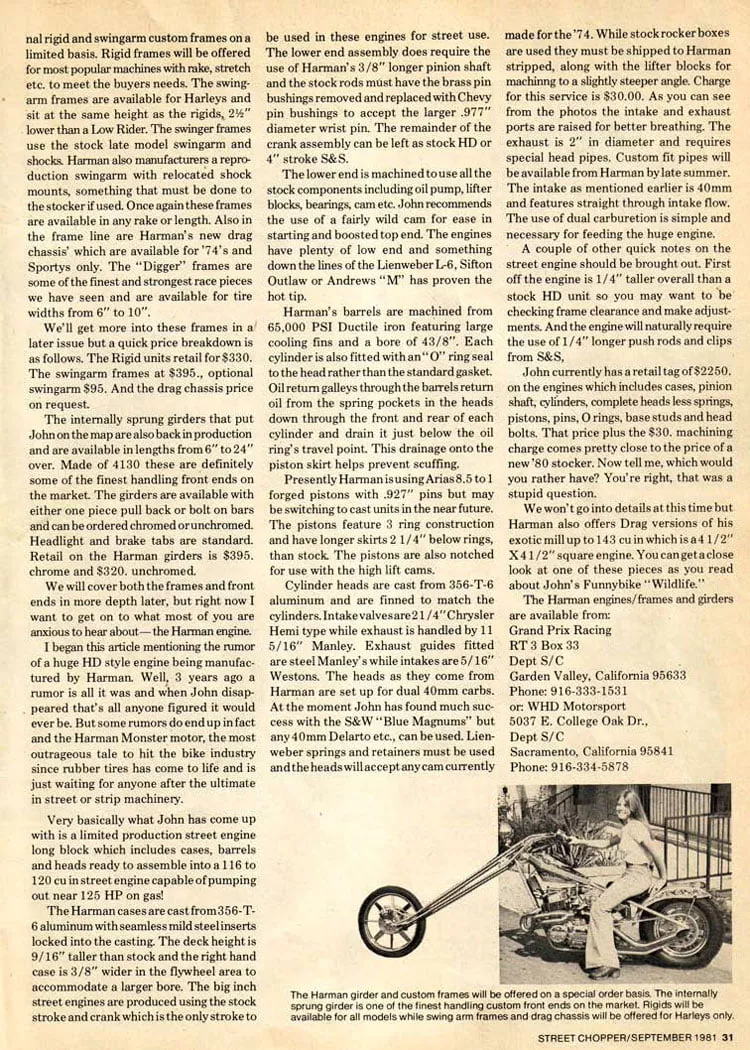

When Harley stroker flywheels became rare and pricey, Harman started making those too. Flywheels were flame cut and heat treated to 36 Rockwell. Each weighed 9 pounds with a 4.75-inch stroke. The barrels were cut from 2024-T3 billet aluminum then fitted with steel sleeves and bored to 3-5/8 inches. Barry Gerolamy did John’s heads at Cylinder Head Engineering back then. He’d raise the ports and make it possible to run the dual carb setup properly. Eventually, the Digger style led to John Harman building his own proprietary V-twin in ’81. It was a limited-production long-block street engine that included cases, barrels, and heads and came ready to assemble in either 116- or 120-inch configurations. The cases were 356-T6 aluminum with seamless mild steel inserts locked into the casting. John used a stock Harley stroke and crank. The deck was 9/16 inch taller than a stock Harley motor, and the right-hand case was 3/8 inch wider. Its stock connecting rods required Chevy pin bushings to accept the larger-diameter wrist pin. Customers had the option of using a stock H-D crankcase assembly (for the rest of it) or a 4-inch S&S version. The lower end was machined to run stock Harley elements, but John recommended a pretty wild cam for his big, bad mill. Its barrels featured large cooling fins and 4-3/8-inch bore. Also, the cylinders had O-ring gaskets at the head instead of the standard stock H-D used at the time. The heads were set up for dual 40mm carbs. John ran an exhaust that was 2 inches in diameter and required a special header. It retailed for $2,250. Drag versions were also available, up to 143 ci.

Executive Choppers

(916) 780-6508

You can see more great chopped iron here.