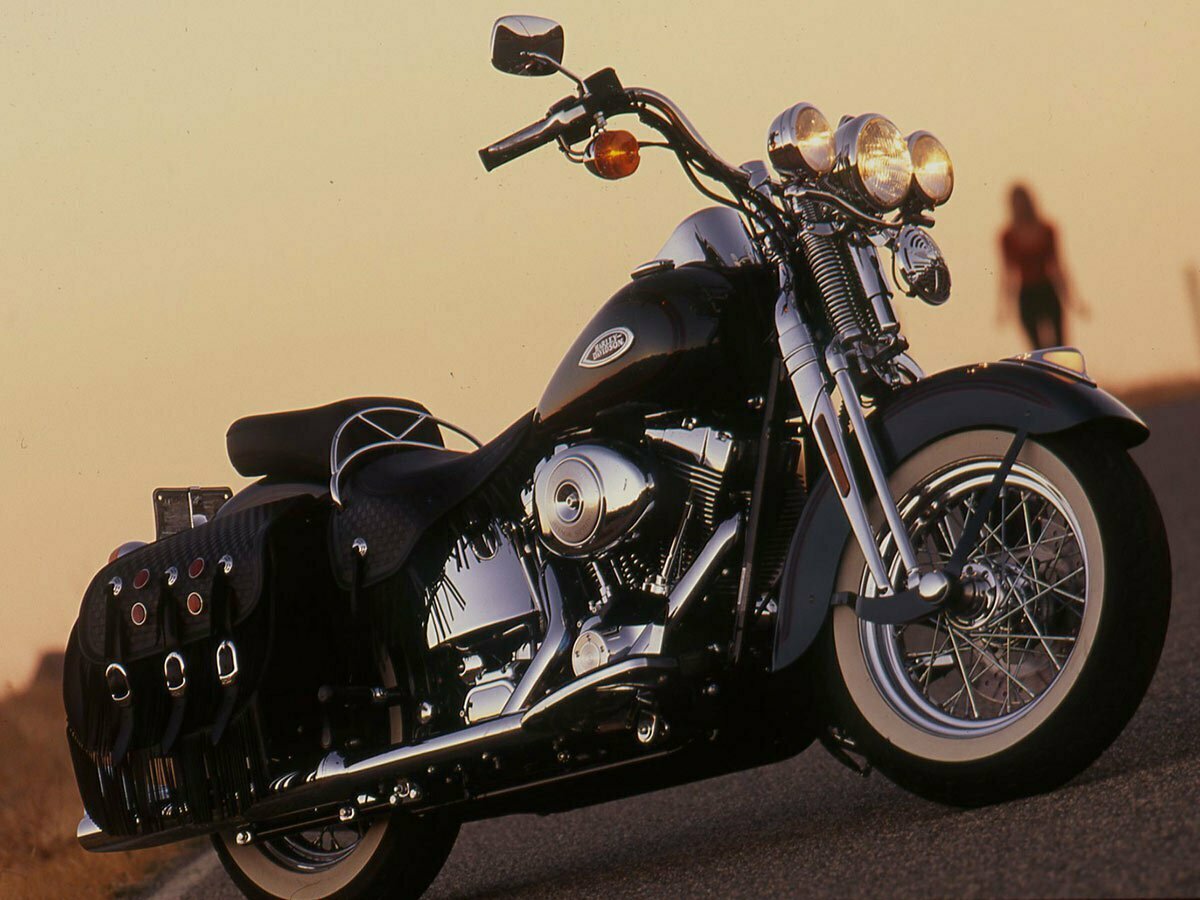

Riding Impression of the 2000 Harley-Davidson Springer Softail

The FLSTS Heritage Springer Softail is a machine you could easily imagine riding from one coast to the next.

Brian Blades

This article was originally published in the December/January 2000 issue of Cycle World’s Big Twin magazine.

Your first ride on the FLSTS Heritage Springer causes a complete disconnect: Your eyes have told you what you just hopped on, but every other sense is telling you that it’s something different. From throttle response, to power, to vibration, to shifting, to braking, this isn’t the Heritage Springer you may have known before. More than that, it doesn’t even feel like any Milwaukee product you’ve ever experienced. It feels taut and solid and slick, as disparate from its appearance as would a 1948 Buick fitted with an a current E-class Mercedes powertrain and suspension.

Welcome to the Beta Zone. Like all Y2K Softails, the Heritage Springer gets the new Twin Cam “Beta” engine, and a completely redesigned chassis to match. The redoing of the Softails “was the biggest project the company has ever done,” says David Rank, Softail Platform manager for Harley-Davidson. Almost everything you see is new, to the point where Rank finds it easier to list the old parts. “The headlight bulb itself, the axles, the right gas cap, the horn and the handlebars—that’s about it,” he tallies.

Oh, you can feel the engine, but the smoothness, if you’re used to an EVO Softail, is almost eerie.

Brian Blades

The big change, though, is in the engine. From the very beginning, Harley’s planners, designers and engineers knew they couldn’t just drop a rubber-mounted engine into a Softail chassis; the hardtail-look rear suspension wouldn’t work with rubber mounts, and besides, the rumble from a solid-mounted engine provided too much of the basic feel that so many riders found so appealing. At the same time, they wanted to reduce the vibration that compromised the high-speed cruising comfort of Softails.

Their answer to that thorny question is what makes the Beta engine different from rubber-mount Twin Cam motors: twin contra-rotating balancers (see “Balancing Act,” page 40). The cleverest thing about the balancers is that you have to be pretty sharp-eyed to see any evidence of their existence. They hide in bulges in the main crankcase, of which only the front one, below the oil filter, can be seen at all.

But, boy, can you tell that they are there! Thumb the starter on the Heritage, and the engine spins quickly to life. If you’ve pulled the enrichener knob out even a little bit, the Twin Cam 88 finds a smooth, quick idle. Blip the throttle, and the revs rise much faster than engine speed ever increased on any Evo; thank the Twin Cammer’s lighter flywheels, which, on the Beta motor, even have slightly less inertia because of the lower, 50-percent balance factor allowed by the counterbalancers. But what astounds is how placid the bike remains at all times. Let the idle lug down below 1000 rpm, and nothing jumps or shakes. Blip it up to 3500, and nothing buzzes. The rear-view mirrors are so steady, you could shave in them while the engine is running and not end up with a faceful of razor nicks and missed stubble. Oh, you can feel the engine, but the smoothness, if you’re used to an Evo Softail, is almost eerie.

When you ride away, that eerie sensation remains. First, the transmission clicks into gear with a buttery precision that’s unique to the new Softails. Grab a handful of throttle and the big Heritage accelerates hard—not something you could say about a stock Evo Softail. Credit the extra power and torque of the Twin Cam for that, as well as the new, shorter gearing. Evo Softails for the last several years were fitted with Bonneville-quality gearing that kept the revs low out on the highway to minimize the buzzing, but that drained the engine’s vigor. Now, with the buzzing tamed by the balancers, Twin Cam Softails get the same gearing as Dynas, and respond accordingly.

And the smoothness stays as you click—yes, literally click—through the gears. At 70 on the highway, the feel is once again surreal to a long-time Softail rider; the buzz is gone, and the Twin Cam Heritage rumbles along as peacefully as did an Evo at 45. Only when you brutalize the speed limit and push the bike to 80 and beyond does the vibration even begin to intrude.

No sad faces aboard this iron pony; it’s all fun and smiles on the Heritage Springer Softail, thanks in no small part to its silky-smooth, counterbalanced Twin Cam 88 engine.

Brian Blades

The cool thing, though, is that the vibration has been exorcised without causing the complete isolation that you get with rubber mounts. You can still feel the texture of the engine, the rumble of its power pulses, the subtle difference in engine feel between power-on cruising and slightly rolling the throttle off. Certainly, the rubber-mount Big Twins are smoother at fast road speeds, but they achieve that through isolation. It’s a little like putting your annoying mother-in-law in a soundproof glass booth: You don’t have to listen to her bitch, but you lose anything nice or useful she might say, as well. With the Twin Cam Beta, Harley has foregone the glass booth but given the mother-in-law a personality transplant that makes you want to be around her.

Similarly, the new transmission shifts so slickly that you may choose to use it more often. The shift lever requires slightly more effort and responds with more mechanical feedback than do those of most imported bikes, but the clunk is gone, as well as any difficulties in finding neutral—even from second gear. The new shift mechanism is so good that it begs the question: When will it be fitted to the rest of Harley’s line? Rubber-mount models in 2001 is the buzz, but there is no talk from The Motor Company about doing something similar for Sportsters and Buells (which is unfortunate, considering how poorly they shift compared to the new Softails). And while the Twin Cam certainly has the power and torque to support lugging in top gear, it also responds well to a quick downshift, revving out on top a good 800 rpm past the point where an Evo would sign off. So, both the transmission and the engine encourage harder use than did the Evo.

With the Heritage Springer, Harley’s engineers followed the same path they took with the rest of the Y2K Softails except for the all-new Deuce: change everything without changing anything.

Brian Blades

Equally changed is the basic handling character of the Heritage. The Twin Cam Beta engine bolts solidly to its redesigned gearbox, which has a boss that carries the swingarm pivot. That powertrain package then bolts very solidly into a redesigned Softail frame. According to Harley’s engineering team, the new frame with engine installed is 35 percent stiffer than last year’s version.

You can feel that stiffness in a newfound sense of solidity and precision with every steering input. The handling is so reassuring, though, that it’s all too easy to stuff a floorboard or a muffler end into the pavement while cornering. The first is no problem, but the second begins to lift the rear tire. Just keep in mind that no matter how good and stable any of the new Softails feel in corners, they’re no VR1000s or Buells.

This fundamental change in character for the Heritage Softail dramatically expands its range of usability. Previously, a Road King or an Electra Glide always emerged as the serious Harley of choice if you were going to tour or spend a lot of time on the highway; the vibration alone of the FLST/FXST models ruled them out of life in the fast lane for extended periods—unless you happened to have an unusually high tolerance for days-on-end vibration. But the TC-Beta Heritage Softail works well as a touring bike, with a stretched-out riding position many will find more comfortable even than that of the FLs. It’s a machine that you could easily imagine riding from one coast to the next, and its overall handling and feel offer you a reason to choose it over some of The Motor Company’s more conventional touring alternatives. With the new Softails, purchase decisions just got more complicated.

On top of all that, the little details Harley has included on this new Softail are appreciated, from the fork lock integrated into the steering head (mandatory in some European countries, by the way), to the new, illuminated fuel gauge and the single gas cap, to the easier oil drain. Even some of the long-standing Softail bugaboos, such as a harsh rear suspension, have been tamed if not entirely eliminated. The revised mounting of the twin, under-engine shocks minimizes friction and takes some of the harshness from the ride, though the Heritage is still not a bike that handles big or sharp-edged bumps happily. And while the fringed, leather saddlebags look great and offer a surprising amount of room, the three straps and buckles per bag get a little annoying about the third time you find yourself rummaging for something at a gas stop.

But the rear suspension and the saddlebags are just about the only demands the Heritage Springer imposes for the sake of its nostalgic style. And it offers quite a lot in return. When you’re cruising down an open two-lane at sunset, pink clouds glowing in the expanded reflections in the three headlight shells, the Twin Cam Beta engine rumbling smoothly and strongly, the Heritage carrying you along with little more need for control than a well-trained horse, you know that all is right with the world, and that you’re exactly where you want to be.