Speed’s Spotlight | Gearin’ Up

A few issues back we talked about that next performance move after a basic Stage 1 setup, how following up a free-flowing intake and exhaust with a little more cam makes good sense (“Grinds For Grunt!” Hot Bike August 2011). And for a daily-ridden street bike “a little more” was the operative phrase; going too big with the cam selection, the guys at Speed’s Performance Plus (SPP) warned, can be a step in the wrong direction. “For an otherwise stock 88-inch motor, a 510 grind is plenty,” Speed’s Jamie Hanson advised. “And for the 96-inchers, it’s a 525. Both work fine with the stock heads and valve springs, have lots of low- and mid-range pull, and coupled with everything else done, they’ll bring another 10 horsepower to the game and 10 more lb-ft of torque.” All that’s certainly welcome, but that’s just the icing on the cake according to Jamie. While swapping cams might be the next logical performance move for a lot of riders, it’s also an opportunity to strengthen up and bulletproof a couple seriously vulnerable areas in a late-model Harley Twin Cam engine.

A Twin Cam, as the name implies, has a pair of chain-driven camshafts operating the valves. And it’s those chains, or more specifically their tensioners, that can be a real problem. Along with that, a Twin Cam’s oiling system, especially at idle and low-rpm, can be marginal at best. Making that switch to performance cams is the perfect opportunity to address both those problem areas once and for all.

<div class="st-block quote text-

Notice: Undefined index: st_text_align in C:laragonwwwhotbike-importblocksquote.php on line 1

“>

Working inside the cam chest is also the perfect opportunity to address that second problem, a Twin Cam’s oiling woes.

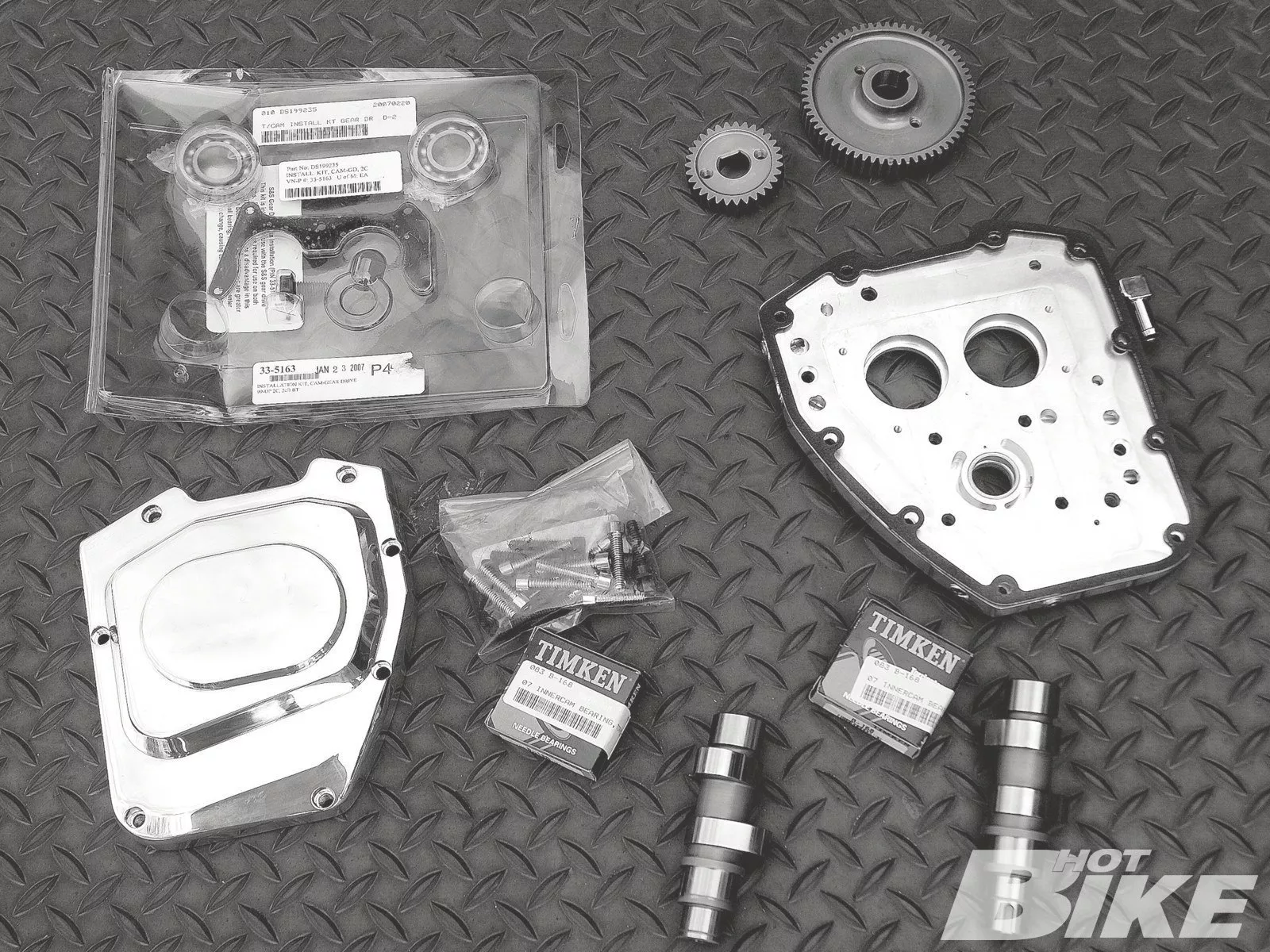

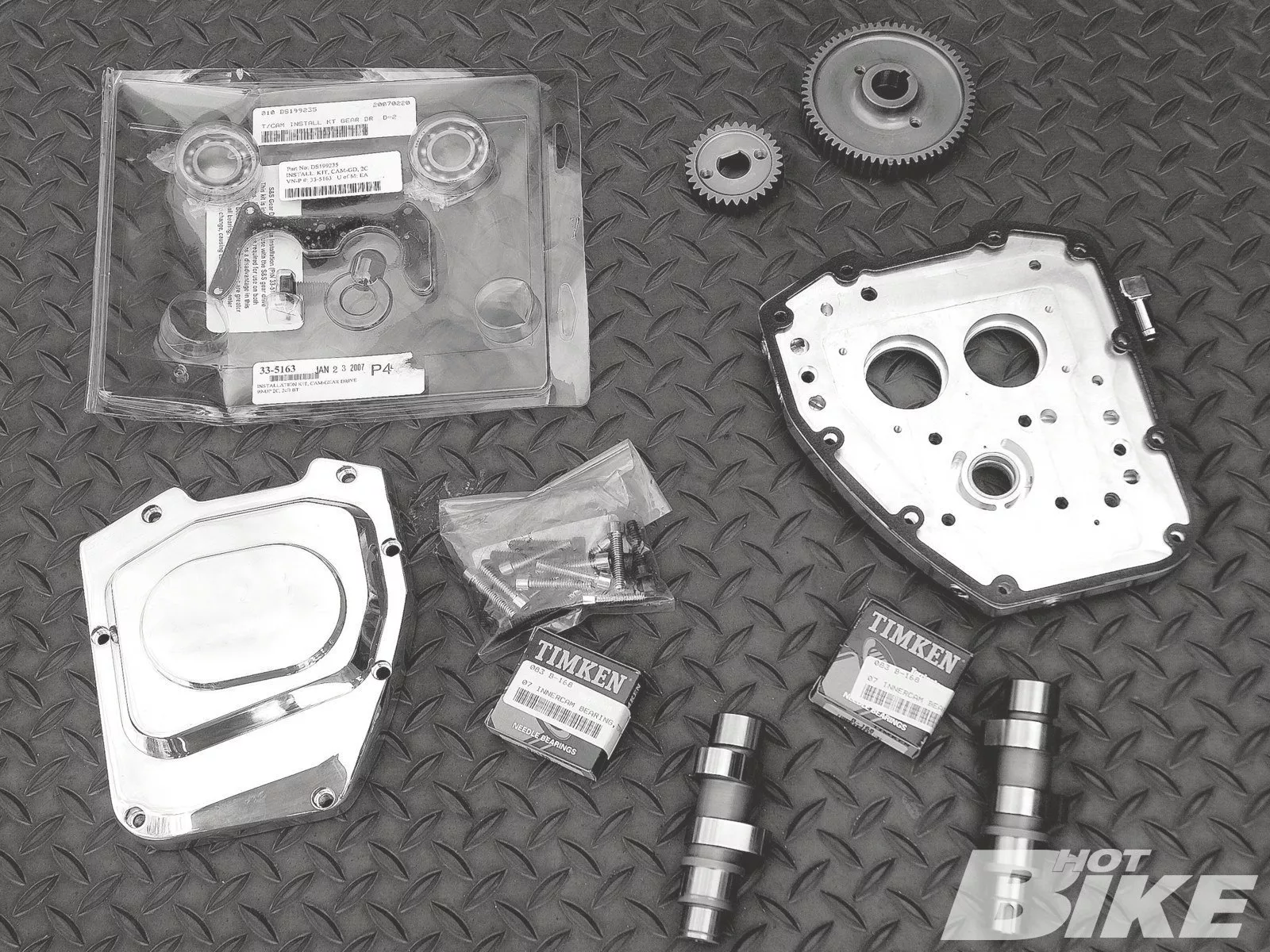

First, that factory chaindrive. Along with the new cams it’s well worth the extra money (a few hundred dollars) to eliminate the chain entirely and include a replacement gear drive. You’ll never worry about tensioners again. The earlier model bikes,’99-06, are the worst offenders here. Their tensioners, in place to maintain some degree of cam-timing integrity as the chains stretch, are spring loaded with some pretty stout springs. Besides robbing who knows how much power just to turn things over, it doesn’t take long for the rubbing blocks on the tensioners to wear away and even break up. By 2007, the factory switched to hydraulic tensioners, alleviating the problem somewhat but not eliminating it. Original Twin Cam service bulletins called for tensioner replacement every 30,000 miles. That’s since been revised down to 20,000 miles. The choice is clear: repeatedly replace the tensioners or cure that problem with a gear drive.

Properly installing a gear drive isn’t as straightforward as it might seem, though. Done correctly, the gear lash should be checked in three places as the drive is installed and rotated. A lash of 0.005 inch or so is the goal. Quality gear sets, such as S&S’s, offer oversized and undersized gears to adjust that lash. Skipping this step, Jamie says, is the cause of most complaints people have about a gear drive. “If the gears are too tight, you’ll get a loud and noticeable whine,” he says. “Leave them too loose and there will be lots of clanking and clunking.” However, take the extra time to make sure everything’s set right, and you’ll be good to go and should be done with any cam-drive problems forever.

Working inside the cam chest is also the perfect opportunity to address that second problem, a Twin Cam’s oiling woes. Pressure, especially on those first-generation TCs, can hover around zero at idle. Once those chain tensioners wear away and brake up, things only get worse. The little pieces have to go somewhere, and as often as not, it’s straight into the oil pump. At a minimum the pump’s internals will be scratched and scored, taking efficiency even lower. At worst, and not at all uncommon Jamie says, the pump will be completely broken. Replacement, of course, is necessary in either case but going the extra step, SPP will shim the pressure-relief valve while they’re at it, building more oil pressure and flow at those critical idle and low-rpm ranges. The ultimate cure is a billet replacement for the OE cam-support plate. On late-model 96ci engines it’ll fit real bearings on the outer camshaft journals, where a factory plate has none, and in the earlier engines it’ll allow the use of a better, late-model oil pump. That new plate is also a lot thicker than the factory piece so there’s no flexing, it has improved oil passages, a much better relief system, and better venting. Whenever the budget permits, Speed’s highly recommends it.

Talk with the guys at Speed’s Performance about all of this, and check their website. Switching to the right set of cams is a smart performance move. Done correctly it’ll also make that bike a lot more dependable. HB

Source:

Speed’s Performance Plus

speedsperformanceplus.com

(605) 695-1401 | (605) 695-2272

(386) 405-7898