Mule Motorcycle’s Racing Replica

The MMRR (which stands for Mule Motorcycles Racing Replica) is a classic racer-on-the-street.

Jeff Allen

This article was originally published in the April-May 1999 issue of Cycle World’s Big Twin magazine.

Professional dirt-track racing, just in case you didn’t know, is in serious trouble. The racing itself is close and exciting and fair, but there’s just one factory involved: Harley-Davidson. And that one factory has just one rider: Scott Parker, who has won the national title nine times, which is three times more often than anybody else, ever.

That’s Problem One. Problem Two is that ever since H-D introduced the XR750, the dirt-track machine that has ruled the roost since 1972, fans have wanted a street version. But the factory has always insisted that it can’t be done.

Which brings us to Problem Three. Largely in response to the first problem, the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA), which sanctions all Grand National dirt-track competition, has drawn up rules for a new class, called SuperTrackers, for production-based Twins displacing up to 1000cc. SuperTrackers goes national this year, running as a support class at 10 National Championship events on select miles and half-miles. If all goes well over the next few years, SuperTrackers will replace the current Grand National class, probably as early as 2002.

So?

So, Mule Motorcycles, a one-man operation of which nobody’s ever heard, offers for your inspection an XL-powered bike that meets the SuperTracker rules, and that can be registered and ridden on the street. It’s called the MMRR, for Mule Motorcycles Racing Replica, and it could be put into limited production, albeit buyers will have to pay for what they get.

That “one man” at Mule Motorcycles is Richard Pollock, who works out of his converted garage in Poway, California. His day job is with Lockheed-Martin, the folks who bring us the Atlas missiles. He works in the Precision Components section, where they make, well … precision components. His motorcycle literally meets NASA standards; and if dirt-track isn’t rocket science, it’s at least rocket technology.

Polluck had developed kind of a cottage industry converting Sportsters into race-replicas.

Jeff Allen

About the odd name: Mules are hybrids, smarter than one parent and stronger than the other. Pollock admires mules, so when he realized he was building hybrids, that was the name he put on the door.

Pollock’s main hobby is dirt-track racing. He’s an active member of the San Diego Flat Track Association and currently competes on a Yamaha YZ400F, a four-stroke motocrosser he has converted to dirt-track specs.

As sort of another hobby, Pollock hooked up with some Japanese tuners working with Harley-Davidsons—yes, there are legions of Harley fans in Japan—and had developed kind of a cottage industry converting Sportsters into race-replicas, both dirt-track and roadrace style.

Here’s where all this separate fact begins to come together. Sundance, the Japanese Harley outfit Pollock works with, has done some impressive work on the XL engine, especially with XR-style heads. Thus, Pollock has come to know the XL engine and the people, at home and abroad, doing improvements on it.

And he can make just about any part, to any spec, in just about any material.

And he knows racing, as well as the serious problems dirt-track has been having for the past generation.

And he knows the plans for the new rules.

And he holds an interest in C&J Frames, just up the road in Fallbrook, California, where the Harley team and the top private tuners go for the latest in XR frames.

For the past 25 years, ever since Harley’s XR750 became the standard of flat-track racing, people have been adapting them for the street. There are XRs converted, as in the XR engine with an alternator or generator and kick start; there are iron-top XL engines in XR frames; there are XL frames, engine and running gear with XR bodywork; and there are Evo XL engines wedged into XR frames.

That last example is the most practical, aside from the fact that the Evo XL engine is bigger than the XR engine, meaning that installing one calls for a lot of bending and grinding and tweaking. And worst, the engine isn’t in its optimum location when all the cramming is finished.

Pollock’s Mule began with a C&J frame, the very latest model, except that current dirt-track practice uses one large, centralized shock and spring, whereas Pollock wanted two conventional shocks. So, he cut off the back of the C&J version and fabricated his own aft portion while making it longer so the XL engine would fit where the weight distribution, fore-and-aft and side-to-side, was just where it ought to be.

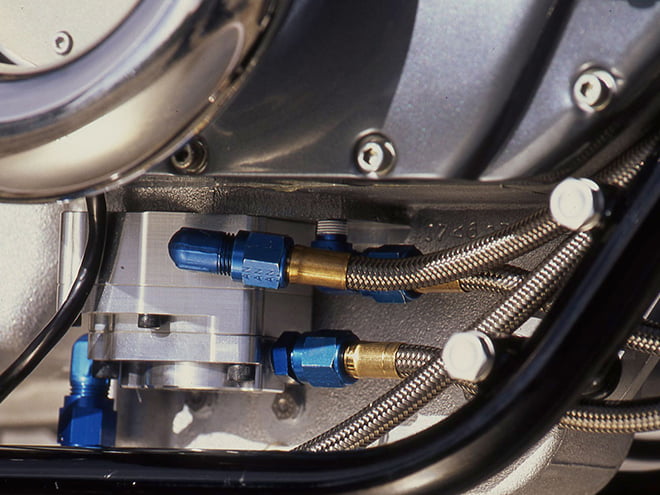

To prevent any possibility of wet-sumping—which, among other problems, can cause smoking and a loss of power—the oil pump is a Zipper’s unit capable of pumping four times as much oil back into the reservoir as from it. And, because it’s external rather than internal as on stock XL motors, the pump can be removed with the engine still in the frame.

Jeff Allen

Stock XRs (Yes, ma’am, there are such things: H-D made a couple of hundred and then switched to selling engines and helping builders find their own frames, glass, etc.) use an oil tank below the seat. C&J frames, however, store the engine oil, two-plus quarts of it, in the frame backbone, freeing the space below the seat. That’s where the Mule has its battery, a sealed, high-output Yuasa unit Pollock located through the Sundance connection.

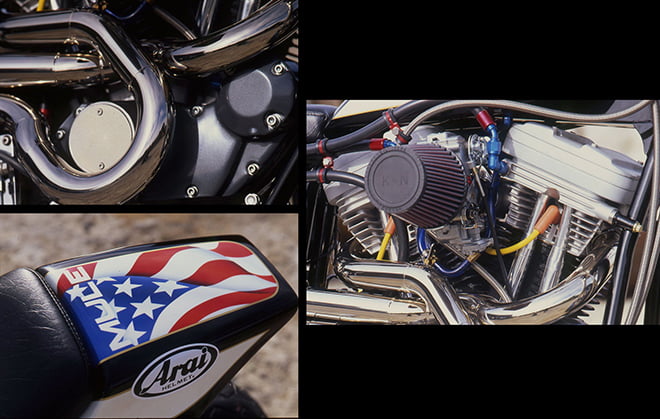

Swingarm is C&J, as used on the company’s twin-shock chassis, with Progressive Suspension dampers. The dual shocks are there partially because they’ll work just fine for this application, and partially because Pollock did not mind a touch of the traditional Harley-Davidson look, witness the black-and-white paint and the tank decals.

With old and new comes borrowed, right? The fork is a combination of parts, as in the actual stanchion tubes and sliders are from a Honda CBR900RR, mounted in triple-clamps fabricated by Mule. The rake and the offset between the steering stem and the tubes are a compromise between dirt and road settings.

Front hub is from a Yamaha TX750. Ask your dad, who’ll recall that the TX750 engine of the mid-Seventies was a disaster. But the hub is strong and readily found at the recycling yard. It has a 36-spoke pattern that works with the Akront rims and, most important, it carried a large brake disc, one made before cost-cutting became rampant. The disc is alloy, with lots of chromium in the mix, and even after 25 years in the salvage yard it’s easily trued and resurfaced. It also is compatible, thanks to deft machine work, with the Grimeca calipers, pads and master cylinder.

Using the same principles, the rear hub is Barnes, a classic dirt-track name, with Nissin caliper and pads, and a disc from a Yamaha RD350—again, a quality component, easily found new or used, never mind the country of origin.

Pollock chose 18-inch wheels rather than the 19-inchers required by the AMA for Grand National racing. He opted for the 18s because for street use, the choice of tires is much better for the smaller, wider rims.

As seen here, the Mule is fitted with Bridgestone Battlax tires, aggressive road rubber that will serve on hard-packed dirt of the racetrack variety; the rims will also accept pure roadrace tires, rain tires, street tires or even knobbies, from most major brands.

A couple of different if traditional features are the big headlight and tach. The light comes from Yamaha’s SR500, but in black, it looks like it’s right off a Vincent or a Brough. And the size permits use of a serious quartz-halogen bulb.

Mule’s exhaust pipes are stainless steel, while the ignition cover is done in space-age scrap alloy. The gearcase cover (behind the pipes) is coated in statuary bronze and has been cut back for access to the high-scavenge oil pump. Carburetor is a flat-slide 41mm Keihin on an S&S manifold. The cylinder heads are XLH1200, ported and reworked internally.

Jeff Allen

The engine in the MMRR began life as a 1986 XLH 1100, bored to 3.5 inches, which comes out to 1200cc. Because this prototype won’t be raced—officially, at least—it was built to have more displacement for the street so it could deliver power equal to that of an all-out racing engine but with less stress and noise. The cylinders, from C.R. Axtell, are cast iron all the way through; the additional strength and reliability are reckoned to make up for the added weight and heat retention.

The cylinder heads began life as stock XL, but they’ve been ported and reworked by Dan Baisley in Portland, Oregon, who also blueprinted the flywheels. Cams are from Andrews, pistons are Wisecos, Carillo supplied the connecting rods, and the dual-plug ignition is from Crane. The single carb is a 41mm Keihin flat-slide.

On the primary side, the cover was adapted to carry the left footpeg and shift linkage: a linkage was needed because the peg has been moved aft, for that classic dirt-track racing posture. The right-side footpeg, as well as the mount for the rear-brake pedal and master cylinder, were fabricated by Pollock because the stock items were too big and heavy.

Pollock experimented with finish, as in the gearcase powdercoated in metallic gray and the primary cover in what the catalog calls statuary bronze. The exhaust pipes are stainless steel, top grade and polished, with heat shields for the rider but not a lot—okay, not any—baffling.

First Klass Glass supplied the tank, rear fender and seat, and they are exactly what the firm supplies to the pro racers. Harley-Davidson handed that part of the business over to private firms when it became clear that small, outside operations could make a living from what is a losing proposition for a big corporation.

Actually, there’s something of that philosophy theming this entire project. Pollock is a master craftsman and a racer, and that’s how he thinks and builds. And his workmanship speaks for itself.

But some of the details don’t. See that shaft just in front of the gearshift shaft on the primary cover? Everybody who’s ever worked on an XL or XR engine knows the bother of setting valve clearances or timing by removing the cover and bumping the engine forward and back, forward and back, too far and not far enough, just to get the pistons set in precisely drop dead center or 36 degrees BTDC or anywhere, actually. The added shaft allows the engine to be minutely rotated from without, cover still in place. This is how Richard Pollock thinks. And that thinking pays off.

Based on aftermarket equipment and the work of Buell, it’s safe to say this 1200 engine will put 100 bhp on the ground.

Jeff Allen

Choosing his words carefully, Pollock says he has gone through stock Sportsters part by part and reached the conclusion that there has been no part on the bike designed or built primarily to be the best or the lightest it could have been.

The factory wouldn’t be surprised to hear this. H-D’s priorities are more on making the best product it can afford to make. But at the same time, Mule’s priorities allow the use of better materials and more time than a mass-produced motorcycle could possibly have.

Parallel to that, Harley has dominated the Grand National series while rarely telling the public about its many championship or its dominant rule, all while spending millions on an ill-fated and, thus far, futile VR1000 roadracing effort.

Neither has H-D offered a street version of the XR. Official word has always been that the company has thought about it, but concluded that by the time the engine would get retuned to meet federal regulations, there’d be little performance left. Which reminds us of the philosopher who once said, “The best way to say I don’t want to do it is to say it can’t be done.”

But Pollock wanted to do it. And his bet, backed up by the Buell experience, is that an XL engine can indeed be tuned for high performance and be legal. He hasn’t yet put the engine on a dyno, but the records are clear in this regard. Based on the various aftermarket equipment available and the work of H-D-owned Buell, it’s safe to say this 1200 engine will put 100 bhp on the ground.

That yields an impressive power-to-weight ratio, thanks in part to the use of titanium and special alloys, and the care taken by Pollock to make each and every part on the Mule as small and light as is practical. This example tips the scales at 385 pounds with oil and its 2.25-gallon fuel tank topped off. Compare that with the 492 pounds of a full-tank 1999 Buell or the even porkier, 520-pound XL1200S Sportster Sport.

Better yet, Pollock says using the factory’s alloy cylinders would subtract 25 pounds from the Mule’s total. Moving in that direction, stripping the bike for racing would easily bring weight close to the 300 pounds normally recorded by an XR750 during the AMA’s tech inspection.

Though the Mule hasn’t been dynoed or clocked at the drags or the dry lakes, a brief ride tells you that this is just about as fast a motorcycle as can reasonably be put on the street. It’s hard to imagine any other production-based 1000cc Twin with more performance, or less weight, than this one has.

What next? Surely there’s a lot of blue sky involved here. Nobody denies that professional dirt-track racing is in need of help, but there’s no certainty that the new rules and entries will be the answer.

But no true-blue Harley-Davidson racing fan doubts that the MMRR—with its classic looks, traditional technology, the very latest in improvements and all the power any pro can handle—is exactly the kind of bike The Motor Company should be building.

Will that happen? Not on the record, no.

But if what it takes to make it happen is a California dirt-tracker with aerospace connections, Japanese suppliers and a pipeline to the wrecking yard, so be it.

This is the classic racer-on-the-street we all should be able to buy.